Anthologising American Poetry

It wasn’t James Joyce in Portrait of the Artist who wrote, ‘anthologise, pluck out his eyes’, but something that sounded like it. These words, in any case, are what come to mind whenever I pick up any new anthology of poetry to see what kind of job has been made of it. And maybe Joyce should have written these words, as a warning to potential editors of poetry anthologies and for the botch they sometimes make. For, where some anthologies of poetry are concerned, the selection criteria – when they can be said to exist – are so perverse that our initial response is to anathematise the editor. But no such response here; it is David Lehman that we should eulogise.

Lehman’s edition is the first to appear in thirty years, when the Yeats and Wilde scholar Richard Ellmann edited The New Oxford Book of American Verse in 1976.  Ellmann’s revised the 1950 anthology which had been edited by F.O. Matthiessen, and in his introduction Lehman pays sincere tribute to these two earlier anthologists, outlining the selection criteria both had adopted for their editions. Lehman regards Matthiessen’s as ‘one of the finest anthologies of American poetry ever made.’ His admiration does not however prevent him from challenging the criteria that Matthiessen used in 1950, though given his very high regard for that edition, he does so not defiantly, but almost apologetically. Lehman writes that, ‘the irony is generally that I agree with Matthiessen’s reasoning and yet in practice find myself frequently obliged to do the opposite.’ Lehman mentions Matthiessen’s first rule: ‘fewer poets, with more space for each.’ Compared to Matthiessen’s 51 poets, Lehman includes 210. (Richard Ellmann featured the work of 78 poets). Matthiessen also decreed, ‘include nothing on merely historical grounds’ and ‘include nothing that the anthologist does not really like.’ Although in agreement, Lehman has slight difficulties with this and gently asks, ‘do I, do you, like Julia Ward Howe’s The Battle Hymn of the Republic, or is like the right word for how we feel about this stirring anthem?’ Then there is the admonition, ‘not too many sonnets’. The danger of over-representing this verse-form, Lehman argues, has long passed, it being more prevalent a form in poetry before 1950. Matthiessen’s fifth regulation ‘to represent each poet with poems of some length’ becomes impossible given the number of poets in Lehman’s volume; and finally, ‘no excerpts’. While Lehman ‘deplores the practice of excerpting long works’, he ‘observes respectfully’ that, just as Matthiessen broke this rule himself, he too has done the same.

Ellmann’s revised the 1950 anthology which had been edited by F.O. Matthiessen, and in his introduction Lehman pays sincere tribute to these two earlier anthologists, outlining the selection criteria both had adopted for their editions. Lehman regards Matthiessen’s as ‘one of the finest anthologies of American poetry ever made.’ His admiration does not however prevent him from challenging the criteria that Matthiessen used in 1950, though given his very high regard for that edition, he does so not defiantly, but almost apologetically. Lehman writes that, ‘the irony is generally that I agree with Matthiessen’s reasoning and yet in practice find myself frequently obliged to do the opposite.’ Lehman mentions Matthiessen’s first rule: ‘fewer poets, with more space for each.’ Compared to Matthiessen’s 51 poets, Lehman includes 210. (Richard Ellmann featured the work of 78 poets). Matthiessen also decreed, ‘include nothing on merely historical grounds’ and ‘include nothing that the anthologist does not really like.’ Although in agreement, Lehman has slight difficulties with this and gently asks, ‘do I, do you, like Julia Ward Howe’s The Battle Hymn of the Republic, or is like the right word for how we feel about this stirring anthem?’ Then there is the admonition, ‘not too many sonnets’. The danger of over-representing this verse-form, Lehman argues, has long passed, it being more prevalent a form in poetry before 1950. Matthiessen’s fifth regulation ‘to represent each poet with poems of some length’ becomes impossible given the number of poets in Lehman’s volume; and finally, ‘no excerpts’. While Lehman ‘deplores the practice of excerpting long works’, he ‘observes respectfully’ that, just as Matthiessen broke this rule himself, he too has done the same.

With anthologies it is always the case of who is in and who is out, and if the editor is good, they will be prepared to give the reasons why! Lehman is one of those confident editors who are comfortable to defend the selections they have made, and this he does with aplomb and style. As the English critic John Sutherland has written elsewhere, ‘the tides of literary popularity are unpredictable’ and to Lehman the words ‘canon’ and ‘canonicity’ should not be shied away from, ‘when they fit the case, as they do so here.’

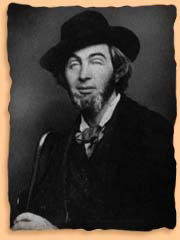

At the centre of the American canon, Lehman places  and Dickinson, saying ‘Walt Whitman is and should be the gold standard in the number of pages allotted, and Emily Dickinson in the number of poems included. They are our poetic grand-parents, these two.’ (For the record, Whitman had never heard of Dickinson, not surprisingly because she was a recluse and only seven of her 1775 poems were ever published in her lifetime. Dickinson herself was to say of Whitman that she ‘had never read his book (Leaves of Grass) – but was told that he was disgraceful.’)

and Dickinson, saying ‘Walt Whitman is and should be the gold standard in the number of pages allotted, and Emily Dickinson in the number of poems included. They are our poetic grand-parents, these two.’ (For the record, Whitman had never heard of Dickinson, not surprisingly because she was a recluse and only seven of her 1775 poems were ever published in her lifetime. Dickinson herself was to say of Whitman that she ‘had never read his book (Leaves of Grass) – but was told that he was disgraceful.’)

Zipping through the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth century settler poets in a matter of a few pages, so observing Matthiessen’s second rule, not to include anything ‘on merely historical grounds’, Lehman devotes the rest of the first third of the book to those born during the nineteenth century, including those who continued to write well into the twentieth. The remaining two-thirds of the anthology is given over to the moderns, those poets born after 1900, beginning with the work of the slightly puritanical Yvor Winters who was conveniently born in that year. It is in the last two-thirds of the book that we see Lehman’s own criteria emerge: no work of any poet born after 1950; all work to be in English; and the term ‘American’ to be ‘broad enough to include poets who were born in other countries but came to the United States to live and contributed tangibly to American poetry.’ Both T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden are claimed as ‘American’. This is not problematic in itself. But if both Eliot and Auden, why not then Thom Gunn, who was English-born, but American by adoption? Gunn contributed more than tangibly to poetry and to the teaching of poetry in the US. But as Lehman writes about the making of any anthology, it is ‘neither an exact science, nor a pure art, but is instead a vision projected and sustained to fulfilment.’ He adds, ‘there is no court of final appeal beyond your own taste, eclectic or focused, wide or narrow, as the case may be’ and indeed he is happy to admit to a weakness for ‘strays’ and for ‘peripheral figures’ whom he is not too high-minded to include. And for the first time, ‘writers of popular song lyrics’ are offered their rightful place within the canon: ‘Empress of the Blues’ Bessie Smith and revolutionary ‘strummer’ Robert Johnson are finally admitted to the American literary pantheon, as are the lyricists Bob Dylan and Patti Smith.

In this mighty publication of nearly twelve hundred pages, David Lehman has brought together the best of American poets and the best of American poetry, and deserves to be congratulated heartily on having undertaken this project. And three more cheers for Lehman for rehabilitating Edna St Vincent Millay, who was banished from the 1976 edition, possibly for being a woman and doubtless for being a sonneteer. His selection is identical to the one I would have made of those poems which I regard as most representative of her work. Thank you, David.

More than a few of the poems anthologised here talk, quite naturally, of the stuff of poetry itself, meta-poems, you might say. Just one is Howard Nemerov’s imagistic sestet, Because You Asked About/The Line Between Poetry and Prose: ‘Sparrows were feeding in a freezing drizzle/That while you watched turned into pieces of snow/Riding a gradient invisible/From silver aslant to random, white, and slow./There came a moment when you couldn’t tell./And then they clearly flew instead of fell.’

The Oxford Book of American Poetry. Chosen and edited by David Lehman. Oxford University Press. 019516251X. £25.

©Michael Lister 2006

Comments