Bibliophage

The first reason is simple: I cannot afford a flat. I cannot even afford a fridge and I suspect hell will freeze over before I move on from the slightly lesser hell of renting. I am also an obsessive, compulsive bibliophage, a phrase bestowed on me by my partner after a swift perusal of Holbrook Jackson’s Anatomy of Bibliomania. I am a book eater. If I see text I have an overwhelming desire to consume it, something that can affect me badly at the dinner table – even at the most scintillating social occasion. At least I am discerning. Tales of woe ‘written’ by porcine, half-witted celebrities fail to grasp my attention. Anything else may be hastily digested as I marshal a comment about the weather (‘cold’ ‘rainy’) to throw into general conversation.

The first reason is simple: I cannot afford a flat. I cannot even afford a fridge and I suspect hell will freeze over before I move on from the slightly lesser hell of renting. I am also an obsessive, compulsive bibliophage, a phrase bestowed on me by my partner after a swift perusal of Holbrook Jackson’s Anatomy of Bibliomania. I am a book eater. If I see text I have an overwhelming desire to consume it, something that can affect me badly at the dinner table – even at the most scintillating social occasion. At least I am discerning. Tales of woe ‘written’ by porcine, half-witted celebrities fail to grasp my attention. Anything else may be hastily digested as I marshal a comment about the weather (‘cold’ ‘rainy’) to throw into general conversation.

I started collecting at the age of twelve. A tediously studious young adult, I decided to spend my 99p pocket money purchasing classics from my local bookshop. Relentlessly I made my way through Hardy, Austen and the Bronte sisters. Such grandly romantic tales were interesting to read, even if I quickly decided that boys, in the form of my twin brother and his friends, were nothing to get excited about. Tess of the d’Urbervilles obviously lived in a different kind of reality and I shed a tear or two for her sad, strange fate. My book hoarding did not continue until after I had finished my degree. Under the utopian socialist auspices of this present Labour government, English students are charged for their higher education. As tuition fees rose, so my burden of debt grew and even 99p pocket money per week began to look wildly optimistic.

Libraries became an invaluable resource, particularly Cambridge’s copyright library, the UL, which looks like something out of Nineteen Eighty-Four. Strange bearded men lived out eternity there eating huge, dry scones in the brown-stained tearoom. During, and then after this scone-scoffing period, I moved around. Peripatetic was the word I used, although to liken my progress to Royal perambulations was a trifle conceited. At least Tudor monarchs could pretend that they were visiting their subjects – for their own good. I moved because I could not stay.

Then I arrived in Edinburgh. For the first time in these years of my maturity I had a room of my own, a place where I could stay indefinitely provided I could pay my rent and didn’t murder my flatmates. I started to discover the meaning of entropy. Piles of books, no matter how neatly stacked, will inevitably and steadily deteriorate into chaos. But this is not quite collecting – it is the hoarding of content. Paperbacks disseminate information to the impoverished masses. They do not really pretend to be aesthetic or durable and I have always carelessly bent a paperback’s ear to mark my place. But I was growing aware of a different kind of book, one that invited clean hands and nurtured possessiveness. Some had splendid gilt tooling, others had fine tipped-in illustration, many were bound handsomely in leather – an era when a cow went that little bit further – others were simply rare.

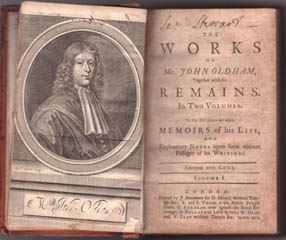

I found myself purchasing a ‘collectable’ book. After several weeks spent picking up and then replacing two volumes of poetry (published in 1722) by a now obscure seventeenth century poet called John Oldham, I decided to transfer his youthful impropriety to my bedroom. After spending 285 years in print I thought he deserved a more considerate home environment than a secondhand bookshop. I also rather enjoyed the idea of owning books that had once been in the possession of Viscount Granville. I hoped Oldham wouldn’t mind such a serious slide down the social scale.

I found myself purchasing a ‘collectable’ book. After several weeks spent picking up and then replacing two volumes of poetry (published in 1722) by a now obscure seventeenth century poet called John Oldham, I decided to transfer his youthful impropriety to my bedroom. After spending 285 years in print I thought he deserved a more considerate home environment than a secondhand bookshop. I also rather enjoyed the idea of owning books that had once been in the possession of Viscount Granville. I hoped Oldham wouldn’t mind such a serious slide down the social scale.

I had become rather hardened in my attitude towards antiquarian volumes of poetry of late (dull), so it was a pleasing surprise to find that Oldham’s poetry was full of youthful vivacity and bitterness. I began with A Satire addressed to a friend, that is about to leave the university, and come abroad into the world and found his words as relevant today as when he first wrote them. He begins:

If you’re so out of love with happiness,

To quit a college life, and learned ease;

Convince me first, and some good reason give

What methods, and designs, you’ll take to live:

His prognostication then gets very dark indeed, as he explains why the clergy is over subscribed and also why tutoring is just another form of slavery in which you are made to depart before the ‘tarts’ – are served. A couple of years ago I wrote a book about surviving your twenties, precisely because I felt, like Oldham, that there was for too much na

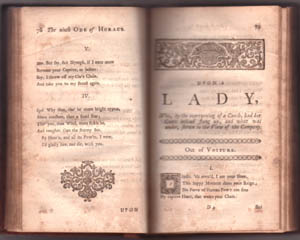

ïve enthusiasm about career opportunities post-university (probably to make that debt seem more palatable) when a dash of realism/cynicism would have been far more helpful. But  Oldham was obviously not the type to nash his teeth for two volumes – his superbly titled Upon a lady, who by overturning of a coach, had her coats behind flung up, and what was under, shown to the view of the company sets out to parody classical love poems. Quite daringly he inserts BUM, but exercises restraint when it comes to an ‘A-H-le’, for which I was at least a little grateful.

Oldham was obviously not the type to nash his teeth for two volumes – his superbly titled Upon a lady, who by overturning of a coach, had her coats behind flung up, and what was under, shown to the view of the company sets out to parody classical love poems. Quite daringly he inserts BUM, but exercises restraint when it comes to an ‘A-H-le’, for which I was at least a little grateful.

It was after this – revelation – that I read the introduction (or ‘memoirs of the life and writings of Mr John Oldham’). A friend of Oldham’s describes him thus: ‘his stature was tall, the make of his body very thin, his face long, his nose prominent, his aspect unpromising, but satire was in his eye.’ What on earth would an enemy say? I was soon to find out. A ‘virulent writer’ and ‘vile traducer’ called Mr WOOD, whose name ‘ought ever to be mentioned but with the utmost contempt’, had tried to blacken poor Oldham’s memory by insinuating that part of Oldham’s The Satires Against the Jesuits was reprinted in an obscene edition of the Earl Of Rochester’s poems. The author (and undoubtedly Rochester) was therefore, ‘mad, ranting, blasphemous and debauched’. Today, sadly, Oldham is neither recognised as a poetic genius or as a debauched madman. History is so rarely kind.

I recently purchased a children’s book, published just after the Second World War. The Bears’ Famous Invasion of Sicily combines fantastic illustrations with a rather sad commentary on mankind’s ability to corrupt. Author and illustrator Dino Buzzati does not stick to soft, wand-waving stereotypes. Instead, he gives us svelte, sword-waving (teddy) bears, a fact that amused me for far longer than you would think possible. A terrible winter forces the bears down into the valley in their search for food: they encounter fighting wild boars, a dubious sorcerer and a house-sized, bear-eating cat. Worse than all these monsters put together, though, is when they discover treachery in their own ranks. It is all very sad and I had to buy it, although the boards were just about off and a child had doodled unimaginatively on an endpaper. For about a week afterwards I kept it wrapped in my bag, ready to amuse anyone I met who was in the least bit susceptible to martial bears.

I recently purchased a children’s book, published just after the Second World War. The Bears’ Famous Invasion of Sicily combines fantastic illustrations with a rather sad commentary on mankind’s ability to corrupt. Author and illustrator Dino Buzzati does not stick to soft, wand-waving stereotypes. Instead, he gives us svelte, sword-waving (teddy) bears, a fact that amused me for far longer than you would think possible. A terrible winter forces the bears down into the valley in their search for food: they encounter fighting wild boars, a dubious sorcerer and a house-sized, bear-eating cat. Worse than all these monsters put together, though, is when they discover treachery in their own ranks. It is all very sad and I had to buy it, although the boards were just about off and a child had doodled unimaginatively on an endpaper. For about a week afterwards I kept it wrapped in my bag, ready to amuse anyone I met who was in the least bit susceptible to martial bears.

Dino Buzzati (1906 -1972) was a painter, playwright, poet, novelist, short story writer, opera librettist, mountaineer, and science fiction writer, and worked as a journalist with the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera. In writing his books, according to The New York Review of Books, he ‘drew on folk tales, but he believed that fantasy should be written with all the detail of a newspaper account’. The bear book was first published in 1947 – the year that the Treaty of Peace with Italy was signed, formally ending hostilities with the allied forced. Behind the gifted children’s storyteller it is difficult not to see a man weary of war and treachery. One of his beautifully vivid, full page illustrations depict bears over-imbibing in a giant wine cellar, some climbing up vats, others slogging back the hard stuff, a few fighting. The caption reads:

New symptoms of corruption among the bears. Ambrose says that in the cellars of a mysterious castle his discovered animals abandoning themselves to shameful orgies. The Account leaves King Leander perplexed and much disgusted.

New symptoms of corruption among the bears. Ambrose says that in the cellars of a mysterious castle his discovered animals abandoning themselves to shameful orgies. The Account leaves King Leander perplexed and much disgusted.

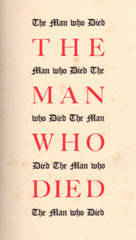

I found myself offering £27.10 (exactly) for a fine copy with D/J of The Man Who Died by D.H. Lawrence, with illustrations by John Farleigh, type format arranged by J.H. Mason, printed by W. Lewis and published by William Heinemann in London, 1935. I had slightly mixed feelings about this, but after I had gone back to see the book and found it packaged up and ready to depart the book fair, I had to make a decision – and fast. My offer was accepted after I had hastily counted small change, and I became the ambivalent owner of one of Lawrence’s last works. I had made it through Sons and Lovers in my teens and had of course read Lady Chatterley’s Lover, for who hasn’t? The latter surprised me for its hard-edged social commentary, but then I should have expected this. I too grew up in the Midlands and it is hard not to feel a societal malaise if you come from there.

Anyway, I tried to read Women in Love a couple of years ago and didn’t make it – I’m still unsure as to whether I really like Lawrence or absolutely detest him. I also had never heard of The Man Who Died. As I later found out, Lawrence finished it just before his death, at the same time as he completed the manuscript of Apocalypse. So, the ageing writer reflects upon death and the mystery of resurrection. Would he be cleaving to docile Christianity? As far as my hasty interpretation is concerned – he did not. The Man Who Died is a delightfully blasphemous re-imaging of what happened to Jesus when he rose from the dead.

To put matters in context: an early draft of this story was first published in 1929 in a limited edition by the Black Sun Press, Paris, under the title of The Escaped Cock. Yes, all kinds of interpretations are valid for this is Lawrence after all, and it was with barely concealed amusement that I came across Jesus’s ecstatic exclamation, ‘I am risen!’ His companion at this point is an attractive and devoted priestess. Shortly before this episode, Jesus philosophically ponders his betrayal by Judas: ‘and in the end I offered them only the corpse of my love… If I had kissed Judas with live love, perhaps he would never have kissed me death. Perhaps he loved me in the flesh, and I willed that he should love me bodylessly, with the corpse of love.’

To put matters in context: an early draft of this story was first published in 1929 in a limited edition by the Black Sun Press, Paris, under the title of The Escaped Cock. Yes, all kinds of interpretations are valid for this is Lawrence after all, and it was with barely concealed amusement that I came across Jesus’s ecstatic exclamation, ‘I am risen!’ His companion at this point is an attractive and devoted priestess. Shortly before this episode, Jesus philosophically ponders his betrayal by Judas: ‘and in the end I offered them only the corpse of my love… If I had kissed Judas with live love, perhaps he would never have kissed me death. Perhaps he loved me in the flesh, and I willed that he should love me bodylessly, with the corpse of love.’

Lawrence himself summarised The Escaped Cock in a letter to Earl Brewster:

I wrote a story of the Resurrection, where Jesus gets up and feels very sick about everything, and can’t stand the old crowd any more – so cuts out – and as he heals up, be begins to find what an astonishing place the phenomenal world is, far more marvellous than any salvation or heaven – and thanks his stars he needn’t have a mission any more.

I still haven’t a clue what to make of the content, but I certainly love the book’s aesthetic. The arrangement of the type format is studiously symmetrical and balanced, cleverly re-working the title. Farleigh’s red and black illustrations also dramatically complement the text -he was known to me previously for his illustrations to Bernard Shaw’s The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God.

I still haven’t a clue what to make of the content, but I certainly love the book’s aesthetic. The arrangement of the type format is studiously symmetrical and balanced, cleverly re-working the title. Farleigh’s red and black illustrations also dramatically complement the text -he was known to me previously for his illustrations to Bernard Shaw’s The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God.

The Man Who Died also has one very special characteristic – it escaped the great flood. I was rather struck by this coincidence. The only (blasphemous) story to feature Jesus in my tiny collection was the one to escape when my ceiling decided to develop a metre -long gap and pour forth water during a huge storm. In a scene reminiscent of the apocalypse (so the media, climate change proponents and stroppy bishops rushed to inform us) water splattered down onto the unprotected boards of Oldham and the bears, but washed harmlessly off the plastic cover in which The Man Who Died was firmly encased. By the time my horrified partner had rescued my books, Oldham and the bears had contracted the book equivalent of flu – namely superficial water damage. Thankfully only the boards were affected, but still, it was enough to make me feel like a bad custodian (I imagine, on a par with feeling like a bad parent) – namely, rotten.

Poor Oldham had made it through the centuries only to suffer another scathing attack: the bears had made it through famine and treachery only to be nearly drowned. And Jesus: what about Jesus? Sexually satisfied and warmed in his priestess’s arms (page 61) – he softly smiles.

© Hannah Adcock

Comments