Robyn Bolam

Angels and Babes

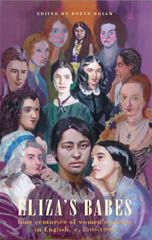

Robyn Bolam’s anthology of poems, Eliza’s Babes, spans some four hundred years of women’s poetry in English, from roughly 1500 to 1900, and draws together work from over 100 poets, including journalists, dramatists, novelists, translators, essayists, dairywomen, domestic servants, a spy, a mill girl, queens of the realm, titled court women, an artist’s model, post-mistresses, and social workers. The title is borrowed from a volume of eleven poems of that name, published in 1652, by a woman of whom we know nothing except that she called herself Eliza. All we know of Eliza is what comes from her poems which, being variously meditative, confessional and epigrammatic, sit alongside those of Eliza’s contemporaries Crashaw and Herbert, and those of the slightly later Traherne and Vaughan.

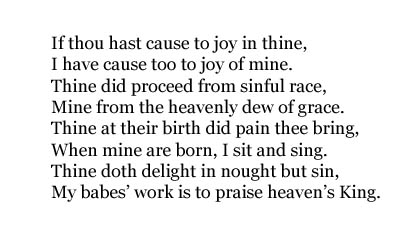

The most striking poem in Eliza’s 1652 volume, written in reply ‘To a Lady that Bragged of her Children’ and in defence of her own writing, expresses more than any of her metaphysical male contemporaries would ever have been able to consider giving voice to: that is, the chastening lyric quoted above. In this poem, Eliza rejects what, for a woman wishing to write, would be the most suffocating expectations of her age (and of every age until comparatively recently): principally those of the roles of wife and mother. In defiance of the mores of her times, by writing her poems and having them published, Eliza achieved what few women, save perhaps for the odd woman monarch, were able to do: to be creative as a literary writer and to hope, through publication, for the survival of her work. Introducing Marxist analysis into the discussion, and also in Woolfian terms, we must assume that Eliza was most certainly not a dairy-maid, but presumably from the upper classes, had an income of say a few hundreds a year and a room of her own, with a lock on the door. Eliza’s poems have shown themselves to be as long-lasting as bronze.

The most striking poem in Eliza’s 1652 volume, written in reply ‘To a Lady that Bragged of her Children’ and in defence of her own writing, expresses more than any of her metaphysical male contemporaries would ever have been able to consider giving voice to: that is, the chastening lyric quoted above. In this poem, Eliza rejects what, for a woman wishing to write, would be the most suffocating expectations of her age (and of every age until comparatively recently): principally those of the roles of wife and mother. In defiance of the mores of her times, by writing her poems and having them published, Eliza achieved what few women, save perhaps for the odd woman monarch, were able to do: to be creative as a literary writer and to hope, through publication, for the survival of her work. Introducing Marxist analysis into the discussion, and also in Woolfian terms, we must assume that Eliza was most certainly not a dairy-maid, but presumably from the upper classes, had an income of say a few hundreds a year and a room of her own, with a lock on the door. Eliza’s poems have shown themselves to be as long-lasting as bronze.

Robyn Bolam writes that ‘the works of male poets are already widely available, but women poets have always been less visible – and more of them wrote poetry during this period than can be included’; and, with understandable regret, ‘it would have needed many more pages to set these women where they belong – cheek by jowl with their male counterparts.’ Within the confines of a little under 400 pages she does bring together an extraordinarily wide variety of female voices which demonstrate the range and variety of poetry written by women through those four centuries, across a variety of poetic movements, styles and subjects and several continents. The only Scottish poets included are Lady Anne Lindsay, Joanna Baillie, Janet Hamilton and Dorothea Maria Ogilvy. Noticeable by their absence are Violet Jacob, Marion Angus, and Helen B. Cruikshank, whose dates alone would have qualified them for inclusion. This absence should be a matter for regret.

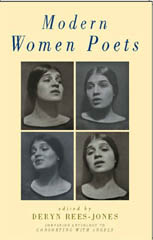

Modern Women Poets, edited by Deryn Rees-Jones, focuses on the female poetry of only one century. This anthology is a companion to Rees-Jones’s pioneering critical study, Consorting with Angels. The poems she has included in her selection both illuminate and illustrate the essays in her critical study, and also represent in their own right an excellent introduction to twentieth-century women’s poetry from Charlotte Mew (d1928) to Catriona O’Reilly (b1973). With its ‘emphasis on the British and Irish poetic traditions and those seminal poets from other countries and traditions who have helped to shape them,’ Modern Women Poets is wide-ranging, though it does not claim to be comprehensive – how could it be? In the introduction, Rees-Jones writes, ‘in making the many choices such an anthology as this requires, I have sometimes had to struggle with the questions that many of the poets were themselves forced to address: that is how to negotiate and value women’s experience in relation to poetry.’ While, as Rees-Jones points out, ‘poems are not simply about experience,’ she does include many ‘poems that address directly those issues that have an overt relationship to women’s writing,’ whether political, personal or aesthetic. In support of this, she quotes Edith Sitwell: ‘a woman’s problem in writing poetry is different to a man’s. This contention – and many others – Rees-Jones explores in depth in Consorting with Angels. While some of the poems selected are familiar, many, to my delight, were new to me. And that always doubles the pleasure. Anthologies, by their nature, are disparate and diffuse, and the poems featured in Modern Women Poets are as varied as the poets themselves. Among the poems that appeal to me most strongly are those written in memory and celebration of certain ‘seminal poets who have helped to shape the tradition.’ I think particularly of Mina Loy’s tribute to Gertrude Stein, which unites intertextually the worlds of science and literature: ‘Curie/of the laboratory/of vocabulary/she crushed/the tonnage/of consciousness/congealed to phrases/to extract/a radium of the word.’ Patricia Beer’s eulogy to Stevie Smith remembers ‘a heroine is someone who does what you cannot do/For yourself and so is this poet/… She struck compassion/In strange places: for ambassadors to hell, for smelly/Unbalanced river-gods, for know-all men.’

Modern Women Poets, edited by Deryn Rees-Jones, focuses on the female poetry of only one century. This anthology is a companion to Rees-Jones’s pioneering critical study, Consorting with Angels. The poems she has included in her selection both illuminate and illustrate the essays in her critical study, and also represent in their own right an excellent introduction to twentieth-century women’s poetry from Charlotte Mew (d1928) to Catriona O’Reilly (b1973). With its ‘emphasis on the British and Irish poetic traditions and those seminal poets from other countries and traditions who have helped to shape them,’ Modern Women Poets is wide-ranging, though it does not claim to be comprehensive – how could it be? In the introduction, Rees-Jones writes, ‘in making the many choices such an anthology as this requires, I have sometimes had to struggle with the questions that many of the poets were themselves forced to address: that is how to negotiate and value women’s experience in relation to poetry.’ While, as Rees-Jones points out, ‘poems are not simply about experience,’ she does include many ‘poems that address directly those issues that have an overt relationship to women’s writing,’ whether political, personal or aesthetic. In support of this, she quotes Edith Sitwell: ‘a woman’s problem in writing poetry is different to a man’s. This contention – and many others – Rees-Jones explores in depth in Consorting with Angels. While some of the poems selected are familiar, many, to my delight, were new to me. And that always doubles the pleasure. Anthologies, by their nature, are disparate and diffuse, and the poems featured in Modern Women Poets are as varied as the poets themselves. Among the poems that appeal to me most strongly are those written in memory and celebration of certain ‘seminal poets who have helped to shape the tradition.’ I think particularly of Mina Loy’s tribute to Gertrude Stein, which unites intertextually the worlds of science and literature: ‘Curie/of the laboratory/of vocabulary/she crushed/the tonnage/of consciousness/congealed to phrases/to extract/a radium of the word.’ Patricia Beer’s eulogy to Stevie Smith remembers ‘a heroine is someone who does what you cannot do/For yourself and so is this poet/… She struck compassion/In strange places: for ambassadors to hell, for smelly/Unbalanced river-gods, for know-all men.’

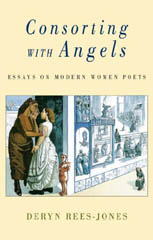

Instead of simply offering a history of twentieth century literary critical theories that can be applied to women’s poetry and attempting to assign to these poets labels from the critical tradition which might not too readily apply, Rees-Jones takes a much more rigorous approach to her subject and offers alternative paradigms for approaching modern women’s poetry. The title of her collection of critical essays is taken from Anne Sexton’s celebrated poem ‘Consorting with Angels’ – ‘I was tired of being a woman/… tired of the gender things./…I am no more a woman/than Christ was a man’. She examines the ways in which twentieth century women poets have attempted to explore and configure femininity in their texts. Part of Rees-Jones’s argument is that while women writers are constantly having to negotiate their gender, they are also constantly having to negotiate the literary tradition and what it means to write their gender within the potentially confining roles of ‘poetess’ or ‘woman poet’. Drawing on the work of Jacques Lacan, Michel Foucault, and Judith Butler, Rees-Jones considers the issues surrounding ‘performative theories of gender and sexuality’ and the concepts of ‘gender performativity’ and ‘performance of gender’ as they relate to text and poet, arguing that ‘performance of the poem and performativity of the self, specifically a gendered self, must be read as part of a complex matrix between poet, text and speech, which is mediated through culture, intentions, expression, language and the often prescriptive ideas of the woman poet and her role.’ Developing her thesis, Rees-Jones examines the literary and cultural constructions of the woman poet in the early part of the twentieth century, beginning with Edith Sitwell and her attempts to reconfigure herself as a woman poet and her lifelong interest in self-presentation. She then discusses the textual ‘performances’ of Stevie Smith, and how she challenged constructions of femininity through her appearance. In the first section of her book, Rees-Jones also discusses Sylvia Plath’s explorations of femininity and the roles of woman, wife and mother in relation to the role of a writing ‘self’, and the work of Anne Sexton. In the second section, Rees-Jones considers initially the work of those women who were writing in the context of the burgeoning Women’s Movement, before describing how Vicki Feaver, Selima Hill and Carol Ann Duffy were to negotiate feminism and the feminine in their work, while incorporating aspects of myth and fairytale. The final chapters of her study examine the work of recent women poets who construct versions of femininity in relation to national and ‘racial’ identities, discussing the work of Medh McGuckian, Moniza Alvi, Gwynneth Lewis, Kathleen Jamie and Jackie Kay, and the use made of science in the work of Jo Shapcott and Lavinia Greenlaw, and the natural world in the work of Alice Oswald.

Instead of simply offering a history of twentieth century literary critical theories that can be applied to women’s poetry and attempting to assign to these poets labels from the critical tradition which might not too readily apply, Rees-Jones takes a much more rigorous approach to her subject and offers alternative paradigms for approaching modern women’s poetry. The title of her collection of critical essays is taken from Anne Sexton’s celebrated poem ‘Consorting with Angels’ – ‘I was tired of being a woman/… tired of the gender things./…I am no more a woman/than Christ was a man’. She examines the ways in which twentieth century women poets have attempted to explore and configure femininity in their texts. Part of Rees-Jones’s argument is that while women writers are constantly having to negotiate their gender, they are also constantly having to negotiate the literary tradition and what it means to write their gender within the potentially confining roles of ‘poetess’ or ‘woman poet’. Drawing on the work of Jacques Lacan, Michel Foucault, and Judith Butler, Rees-Jones considers the issues surrounding ‘performative theories of gender and sexuality’ and the concepts of ‘gender performativity’ and ‘performance of gender’ as they relate to text and poet, arguing that ‘performance of the poem and performativity of the self, specifically a gendered self, must be read as part of a complex matrix between poet, text and speech, which is mediated through culture, intentions, expression, language and the often prescriptive ideas of the woman poet and her role.’ Developing her thesis, Rees-Jones examines the literary and cultural constructions of the woman poet in the early part of the twentieth century, beginning with Edith Sitwell and her attempts to reconfigure herself as a woman poet and her lifelong interest in self-presentation. She then discusses the textual ‘performances’ of Stevie Smith, and how she challenged constructions of femininity through her appearance. In the first section of her book, Rees-Jones also discusses Sylvia Plath’s explorations of femininity and the roles of woman, wife and mother in relation to the role of a writing ‘self’, and the work of Anne Sexton. In the second section, Rees-Jones considers initially the work of those women who were writing in the context of the burgeoning Women’s Movement, before describing how Vicki Feaver, Selima Hill and Carol Ann Duffy were to negotiate feminism and the feminine in their work, while incorporating aspects of myth and fairytale. The final chapters of her study examine the work of recent women poets who construct versions of femininity in relation to national and ‘racial’ identities, discussing the work of Medh McGuckian, Moniza Alvi, Gwynneth Lewis, Kathleen Jamie and Jackie Kay, and the use made of science in the work of Jo Shapcott and Lavinia Greenlaw, and the natural world in the work of Alice Oswald.

In her introduction to Eliza’s Babes, Robyn Bolam writes that ‘the works of male poets are already widely available, but women poets have always been less visible.’ She is, of course, referring to the period 1500-1900. In Consorting with Angels, Deryn Rees-Jones ends her introduction with a great flourish: ‘women’s poetry is now very much a visible part of contemporary poetry. It is the spectacularity of the work of these women poets – in all senses of the word – who wrote and who have shaped the writing which succeeds them, which demands, in every way, another and a different kind of look.’ In Consorting with Angels Deryn Rees-Jones has paid these women poets that different kind of look.

Eliza’s Babes, ed. Robyn Bolam, Bloodaxe (ISBN 1852245212 PBK £10.95); Modern Women Poets, ed. Deryn Rees-Jones, Bloodaxe (ISBN 1852246782 PBK £9.95), a companion anthology to Consorting with Angels, Deryn Rees-Jones, Bloodaxe (ISBN 1852243929 PBK £10.95).

© Michael Lister 2006

Comments