Dougal Graham

Dougal Graham, the Skellat Bellman

For nearly two hundred years the common folk of Scotland depended for their reading matter on the many thousands of chapbooks and broadsheets that the travelling packmen carried around among their ribbons, pins, garters, lace and other odds and ends. The visit of the packman, two or three times a year, must have been eagerly looked forward to by the folk in the remoter country districts.

For nearly two hundred years the common folk of Scotland depended for their reading matter on the many thousands of chapbooks and broadsheets that the travelling packmen carried around among their ribbons, pins, garters, lace and other odds and ends. The visit of the packman, two or three times a year, must have been eagerly looked forward to by the folk in the remoter country districts.

These chapbooks – literally ‘cheap books’ costing from a farthing to fourpence – dealt with a vast range of subjects. Humour, religion, history, legends, dreams, witchcraft, murders(the Burke and Hare murders produced a grand crop), and even do-it-yourself doctoring, as well as volume after volume of songs and poems, all well represented in the chapman’s pack.

Undoubtedly, the King of Scottish chapbook writers was Dougal Graham, the skellat bellman of Glasgow. He was born at Raploch, Stirling, around the year 1724, and although he was a tiny hunchback he joined the Jacobite army and followed the Prince right through the campaign to Culloden, as a non-combatant. After Culloden he used his experience to write a long doggerel History of the Rebellion, which became one of the most popular chapbooks although it cost the huge sum of fourpence. Dougal then went on to compose and sell a series of chapbooks, full of very broad humour. These were even more popular. One of his friends said of Dougal: ‘Dougal was an unco glib body at the pen and could screed aff a bit penny history in less than nae time. As his warks took weel – they were level to the meanest capacity and had plenty o coorse jokes to season them. I never kent a history o Dougal’s that stack in the sale yet, and we were aye fain to get a haud o some new piece frae him.’ Coarse they may have been , but Dougal’s prose tales are just about the only specimens we have of Scots as it was spoken among the country folk of the eighteenth century. It is wonderfully expressive and the vocabulary is very rich. To give an example of its flavour, here are two auld wives gossiping about their minister and his family:

‘Maggy: But what dae ye think o our minister, is he a guid man, think ye?

Janet: Indeed I think he’s a gey gabby body, but he two fauts, and his wife has three. He’s unco greedy o siller, and he’s aye preachin doun pride and up charity, and yet that fu o pride himsel that he has gotten a glass windae on every side o his nose, and his een is as clear as twa clocks to luck to. He has twa gigglet gilliegaukies in dochters comes into the kirk wi their cobltehow mutches frizzelt up as braids their hips, and clear things like starns aboot their necks, and at every lug a wallopin white thing like a snotter at the bubbly weans nose, syne aboot their necks a bit thin claith like a moosewab and their twa bits o paps playin aye nidity nod, shinin through it like twa yearnin bags, shame faa them and their fligmagaries baith, for I get nae guid o the preachin lookin at them: and syne aa the dirty sherney hought hizzies in the prish maun hae the like or lang gae!’

The quotation, from History of the Haverel Wives, shows that Dougal has great descriptive power. The simile describing the girls’ earrings may not be very delicate but it is certainly graphic.

Dougal’s other chapbooks include Jocky and Maggy’s Courtship, The Coalman’s Courtship, The Comical Transactions of Lothian Tom, Janet Clinker’s Oration, The Ancient and Modern History of Buckhaven and The Comical Sayings of Paddy From Cork. The most striking feature of all his work is its coarseness, its earthiness. Dougal’s Scotland was certainly not a land under a bleak and joyless Calvinist dictatorship, as some people have imagined. His Scotland seems to be a pagan society, scarcely touched by Christianity.

But Dougal’s is not a complete picture of the Scotland of our ancestors. While his bawdy tales sold in their thousands, so did many a dreich volume of sermons and lives of Covenanting martyrs. There were also accounts of the lives and deaths of children of unnatural saintliness. For example, A Brief Memoir of Urcilla Gebbie, who died at Galston on the 28th of August, aged 15 years – an age at which, if we are to believe Dougal, most young Scottish females were enjoying their first seduction.

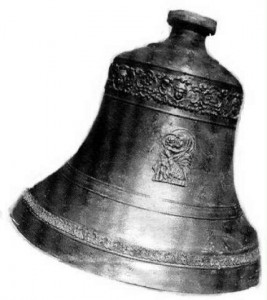

In addition to being a best selling author, Dougal enjoyed the official position of skellat bellman of Glasgow. The skellat bell was the one used for ordinary announcements by the town cryer, whereas the mort bell was used to intimate deaths. And a kenspeckle figure he must have made as he paraded the streets, ringing his bell and advertising the latest beef that the butcher had to sell – ‘a little man scarcely five feet in height, with a Punch-like nose, with a hump on his back, a protuberance on his breast, and a halt in his gait, donned in a long scarlet coat nearly reaching to the ground, blue breeches, white stockings, shoes with large buckles and a cocked hat perched on his head, and you have before you the comic author, the witty bellman, the Rabelais of Scottish ploughmen, herds and handicraftsmen.’

As specimens of the Scots language before it went into decline, Dougal Graham’s works are well worth reading. And as for the bawdiness that shocked the Victorians, a generation that can accept Billy Connolly will find nothing too outrageous in Dougal Graham.

© David Fergus 1989

Comments