David Roylance

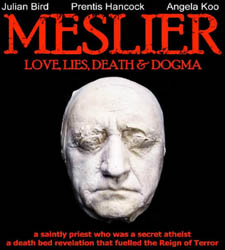

Meslier

I would like, and this would be the last and most ardent of my wishes, I would like the last of the kings to be strangled by the guts of the last priest. Jean Meslier

There are two stories to the play Meslier. First the extraordinary story of Jean Meslier himself, a man virtually unknown outside his home country, France, and a man who unknowingly fanned the flames of a movement that would change the shape of Western Europe forever. Second is the fascinating story of how this play came about.

There are two stories to the play Meslier. First the extraordinary story of Jean Meslier himself, a man virtually unknown outside his home country, France, and a man who unknowingly fanned the flames of a movement that would change the shape of Western Europe forever. Second is the fascinating story of how this play came about.

My name is David Roylance and I am a theatre director. Born and bred in Edinburgh, I find it a real treat and a privilege to be able to return home most Augusts and deliver a piece of theatre to my home city. This year I have directed Meslier by David Hall, from an idea by Julian Bird and Colin Brewer. It has been produced by Abreaction Theatre Company and will be playing in Sweet Venue’s Edinburgh College of Art in the Cabaret space every night at 8.30pm from the 14-27 August.

Jean Meslier (1664-1729) was a Catholic priest in the poor country parish of Etripigny in the Ardennes, where he remained until his death. He was a dutiful priest, beloved by his flock, living in virtual poverty through his entire working life – and secretly was the most ardent atheist.

Jean Meslier (1664-1729) was a Catholic priest in the poor country parish of Etripigny in the Ardennes, where he remained until his death. He was a dutiful priest, beloved by his flock, living in virtual poverty through his entire working life – and secretly was the most ardent atheist.

He did not believe a word of the book he preached from. He wrote his own book, a Testament that he left us on his deathbed, having hastened his own death after finishing his work. His Testament is a vicious and uncompromising attack on all forms of organised religion and the divine right of kings and the aristocracy.

By his own admission, within the Testament, Meslier was a coward. Since the punishment for preaching atheism was burning alive at the stake this is perhaps something we can understand and empathise with. As the director of the play I find it interesting that we are bringing this story to Edinburgh, the home of Thomas Aikenhead, the last man in the United Kingdom to be hanged for preaching atheism.

Meslier died so his Testament could live. He spoke to us from beyond the grave, despite not believing in any afterlife at all. Eventually his work reached Voltaire, who was very impressed with its passionate fervour and sentiment (despite his criticism of the writing style). Voltaire bowdlerised Meslier’s Testament, turning it into a deist document rather than an atheist one and he downplayed the criticism of the monarchy. The text, as you guess from the above quote, provoked strong reaction and contributed to the French Revolution.

The play has been constructed around understanding a man who lived one life by day and another at night. Unlike Deacon Brodie or any of his gothic literary offshoots, Meslier was a passionate defender of a moral code during the day and a fighter for the proletariat during the night. No hedonistic alter ego for this man. In the play we see him through the eyes of his closest friend, Father Claude Buffier, a career churchman and politician who was almost diametrically opposed to Meslier’s ideals. We also see him through the eyes of a woman we named Delphine, who Meslier took into his house as a teenager and educated. She was his housekeeper. We know that these two people did exist. Unfortunately we do not know much more than that. However, as dramatists that has left us a freer hand to create our own understanding of what this man’s life might have been like.

The second story in this tale is how the play came to be. My old friend Julian Bird came to me in January of this year with an outline of Meslier’s life written by fellow psychiatrist Dr Colin Brewer. Julian asked me if I thought the Meslier story had real theatrical potential. Julian is a psychiatrist who turned actor nearly four years ago. Having grown up in an artistic household with a mother who was an actress and father who was a painter, he felt the urge to return to his artistic roots, bringing to bear his unique professional insight. Colin Brewer is one of his closest friends; they have known each other since they trained as psychiatrists together, thus slightly echoing the friendship of two of our major characters.

I told Colin and Julian that the story oozed with potential so they decided to find a writer to turn their idea into a script. Eventually they met with David Hall, author of last year’s Fringe success Cross Road Blues, (a play that received a five star review in the Scotsman) and after an initial exchange of ideas and scenes he was commissioned to put flesh on the creation. It was immediately clear that David writes things for real human beings to say – we have been enormously lucky in finding a writer of this quality.

Three fine actors of talent also grace the play. Bird is playing Meslier himself, Angela Koo is Delphine, and Scottish actor Prentis Hancock completes the team as Father Claude Buffier.

Meslier’s story deserves to be heard and remembered. Politically and philosophically he played his part in a movement that has radically changed the way we think and live our lives. Perhaps without Jean Meslier, there would have been no David Hume.

© David Roylance 2006

Comments