playing cards

The History of Playing Cards

Scotland seems an unlikely place for looking into the history and variety of playing cards. Its tradition would seem, at first sight, likely to frown on such things. But Peter Bruschi, the Dutch or possibly German engineer who, in 1681, set up the first supply of piped water in Edinburgh, is also said to have been one of the first printers of playing cards in the country. So cards have been produced as well as played here for at least some three hundred years. And although the United Kingdom, unlike some European countries, does not have a museum devoted to playing cards, since 1982 Edinburgh has had the only shop in Britain which is exclusively dedicated to playing cards, and to books and information about them – the specialist dealer Roderick Somerville, at whose shop cards from all over the world are available.

Scotland seems an unlikely place for looking into the history and variety of playing cards. Its tradition would seem, at first sight, likely to frown on such things. But Peter Bruschi, the Dutch or possibly German engineer who, in 1681, set up the first supply of piped water in Edinburgh, is also said to have been one of the first printers of playing cards in the country. So cards have been produced as well as played here for at least some three hundred years. And although the United Kingdom, unlike some European countries, does not have a museum devoted to playing cards, since 1982 Edinburgh has had the only shop in Britain which is exclusively dedicated to playing cards, and to books and information about them – the specialist dealer Roderick Somerville, at whose shop cards from all over the world are available.

For those who enjoy the stimulation and tension of bridge or who relax in quiet moments with a game of patience, the interest and excitement of cards is self-evident. But there is clearly a further element about these somewhat unlikely systems of numbers, symbols and pictures which has attracted not only the enthusiasm of players but the interest of artists, designers, writers, composers, occultists, advertisers and philosophers. Among the packs recently and currently available, there are many which have been designed with a far greater degree of invention and sophistication, both aesthetically and conceptually, than would be required purely for purposes of play.

There is a pack, still available, which was originally designed for his own use by Arnold Schoenberg, a painter as well as a composer. Two packs, both under the auspices of cigarette companies, have been produced to designs by Erie, famous for his theatre and fashion work, and for his covers for the magazine Harper’s Bazaar. The expressionist painter Alfred Kubin, author of the novel The Other Side, produced illustrations for a thirty two card fortune telling pack.

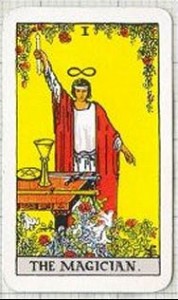

One of the most attractive of Tarot packs was designed at the turn of the century by Ditha Moser, the wife and a former student of the Austrian artist Koloman Moser, one of the leaders of the Vienna Secession and a professor of applied art. The trumps of this Tarot pack are illustrated with domestic and everyday scenes from Vienna and the countryside around. She also produced a whist pack with red, white and black geometric designs, again in the Jugendstil fashion.

There are surrealist cards too. Salvador Dali has created illustrations for two – a tarot pack and the more standard fifty two card game. The French surrealists – including, amongst others, Andre Breton, Rene Char, Rene Daumal and Tristan Tzara – designed a pack during the time they spent at a chateau in the south of France in 1940-41. Some of the background to this project was given by Andre Breton in an article included in the book La Cle des Champs and reprinted as notes to the commercial version of the pack. The views of the surrealists led them to change the suits and their symbols, and the hierarchy of the court cards. The new suits were Love, Dream, Revolution and Knowledge, represented respectively by flames, a black star, a wheel with blood and a lock. The new hierarchy for the court cards was Genius, Siren and Magus (in descending order), represented by Baudelaire, the Portuguese Nun (the writer of the 17th century love letters) and Novalis for the suit of Love; the poet Lautreamont, Lewis Carroll’s Alice and Freud for Dreams; the Marquis de Sade, Lamiel and Pancho Villa for Revolution; and Hegel, Helen Smith and Paracelsus for Knowledge. Altogether a heady mixture for one’s game of bridge.

Since then there have been many packs with new concepts and new illustrations, some of them incorporating designs from a wide selection of contemporary artists – for example, the French Jeu des Peintres in the 1970s (still available) and the recent British Deck of Cards with illustrations by 56 contemporary artists (the designs are also available as postcards).

One of the strongest and most straightforward interests of playing cards for designers is that they represent a cheap and very widely distributed form of applied art. They can combine the satisfaction of getting one’s illustrations to a large audience with a sound commercial project. Other applied arts – glass, pottery, fabrics, fashion clothes, even furniture – only reach a relatively small audience. Playing cards are items which people want to use, rather than having to be persuaded of their cultural importance, and which even in the more sumptuous packs are relatively inexpensive. So it is not surprising that Sonia Deiatnay, wife of the French painter Robert Delaunay and an artist who was much interested in applied arts, should have designed a very practical but striking standard pack – the bridge simultane. The pack remains sufficiently close to the traditional design to allow for its being used in actual play – serious card players are notoriously reluctant to play with non-standard sets – while creating a new, bright and aesthetically pleasant effect.

Another less immediately practical aspect of cards, which has taken the attention of those not initially attracted by the card games, is their existence as a rather strange conceptual of hierarchical values and artificial order, which is disrupted, subjected to the laws of chance, and returned to order by the individual players in competition with others. The shuffling of the pack, and the slow re-establishment of some desired ordering by each of the players, provide a system of symbols operating according to chance and human choice. Even the most simple of games involve some element of matching up the ordering which has been dissolved by shuffling for play, This is the aspect which not only intrigued and delighted the surrealists, but inspired the imagination of the occultists and those interested in psychology.

The decision of the surrealists to create a new modernist hierarchy was not gratuitous – the usual order of king, queen, jack is, after all, explicitly linked to the symbols of a social system. After the French Revolution, there were “revolutionary packs” which replaced the kings with such characters asVoltaire and Rousseau. A later French pack of 1850 replaced the kings with liberators – Simon Bolivar, Washington, Bonaparte and William Tell; the queens were Equality, Republic, Fraternity and Liberty.

Rather than such rearrangements being unlikely, it seems more strange that new packs of cards were not produced in the first years after the Soviet revolution, at the time when the painted trains full of intellectuals such as Mayakovsky were circulating in an attempt to bring a new version of art to the people at large. I asked Mr. Somerville about this recently, hoping that there might be interesting cards from this period. But apart from a couple of packs, not easy to find these days, of anti-religious cards (with God on a cloud pulling the strings of puppets), the answer was that no innovations had been made, and to this day Russian card sets retain the traditional hierarchy of king, queen and jack.

The Tarot pack, although originally created during the 15th century in Italy for game playing, lends itself particularly to more sophisticated systems of symbolic ordering, if only because it has twenty two extra illustrated cards with which to do this. Although the occultists, inspired by the erroneous suggestion of the 18th century French antiquary, Antoine Court de Gebelin, that the Tarot cards were of immense antiquity and contained the ancient wisdom of the Egyptians, got their history wrong, they were not entirely distant from the truth in believing that the ordering of the Tarot pack had some significance beyond the purely functional. The historians of playing cards tell us that the extra cards probably were inspired by the popularity of the illustrations to the poems by Petrarch called the Triumphs (of Love, Charity, Death, Fame, Time and Eternity). This connection was put forward by Gertrude Moakley in 1956, and is discussed in John Shephard’s The Tarot Trumps and the very comprehensive The Game of Tarot by Michael Dummett (a writer on cards who is a philosopher and has written an important book on Frege).

On this explanation the “Trionfi” of Petrarch are seen as the source of the name “trumps”. The poems provide an allegory of the movement of the soul through a progression of states, which form another system of structured symbolism, and give some limited basis, in terms of concept though not of history, to the less extreme claims made for Tarot cards.

The occultists also receive some support from modern psychology for their view that people’s subjective interpretation of the cards thrown up by chance might give some insight into their character, even if not of the future. Today there are many modern Tarot packs, using a wide variety of occult and mythical material, which are intended primarily for fortune telling (although more traditional packs are still used for Tarot or ‘Tarock’ game playing in several European countries). Many of these are designed and produced in Italy, the original home of Tarot.

Other versions of this aspect of chance and choice have been created for card packs without an attempt to link up with “ancient wisdom”. The “Jaro” cards – the name is apparently derived from the Arabic word for neighbour – were invented by Andre Voisin in 1942. The cards are in black and gold, and the lengthy instructions suggest that they can be used for discovery of oneself, and as the basis for plays, stories and poems. They have been used to help create plays and add to theatrical training at various institutions in France and Africa. They have been further developed over a period of forty years, and a pack published in 1983 is commercially available.

In Britain relatively little use has been made of the potential of cards in recent years, but interest seems to be growing. In Scotland, there have recently been a Commonwealth Games pack, a pack depicting Scottish historical characters, a Tartan snap with good reproductions of the designs, a pack to be given away with whisky – presented in a rhomboid box designed to fit on the bottle – and a set of Scottish landscapes taken by the photographer Colin Baxter. Perhaps if museums and galleries become involved in promoting such applied art, the potential of cards can be shown in catalogues and exhibitions, and a new generation of art students can be inspired to keep a pack of cards in their portfolios.

Comments