Arthur Johnston

Apollos of the North

Not exactly household names, except perhaps amongst the most erudite, it was only twenty years ago that I first came across the Scottish Humanist poets George Buchanan (1506-82), historian, satirist and Latin tutor to James VI, and Arthur Johnston (c1579-1641), physician to James VI and Charles I. This was through the translations that Robert Garioch had made into Scots of a few of their poems (and two of Buchanan’s plays), from the Latin in which their work was wrought. At that high point of the Renaissance, it was still the European lingua franca. MacDiarmid too had made some prose translations of their poems, which he included in his 1940 The Golden Treasury of Scottish Poetry.

Not exactly household names, except perhaps amongst the most erudite, it was only twenty years ago that I first came across the Scottish Humanist poets George Buchanan (1506-82), historian, satirist and Latin tutor to James VI, and Arthur Johnston (c1579-1641), physician to James VI and Charles I. This was through the translations that Robert Garioch had made into Scots of a few of their poems (and two of Buchanan’s plays), from the Latin in which their work was wrought. At that high point of the Renaissance, it was still the European lingua franca. MacDiarmid too had made some prose translations of their poems, which he included in his 1940 The Golden Treasury of Scottish Poetry.

Other than a few biographies that appeared in the early years of the twentieth century, to mark the quatercentenary of the birth of Buchanan, and some scholarly editions of his work published in the 1980s to mark the four-hundredth anniversary of his death, Buchanan’s work as a poet has been neglected. The publication in 2000 of The New Penguin Book of Scottish Verse did however begin in its own small way to undo some of the neglect.

Johnston has fared even worse. Though his poems were published and admired during his lifetime, and some were again made available in 1709 by Freebairn and Ruddiman (who also published Buchanan’s Opera omnia in 1715), the only centenary of his that was marked in any way seems to have been the first one, with the publication in 1741, in London, of a new edition of his translations into Latin of the Hebrew Psalms of David. While Dr Samuel Johnson considered Arthur Johnston to be ‘among the Latin poets of Scotland in the next place to the elegant Buchanan,’ he has no entry in any of the editions of The Oxford Companion to English Literature that I have consulted, but he does appear in the new Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Indeed, Crawford writes, ‘in modern times Johnston’s name is almost unknown: so much so that when I first published a few versions of his poems around 2000, some people thought I had made him up.’

Thus Robert Crawford’s undertaking to revive the reputations of these poets in the vigorous translations or ‘versions’ he has made of a selection of their poems is a truly noble enterprise. It is to his great credit that he has taken up the literary torch and in this ‘poetic succession’ paid his own homage to these two formidable poets. The appearance of Crawford’s versions can and should be added to that list of ‘reasons to be joyful.’ One Scottish makar, that is the current Scottish Makar, Edwin Morgan expresses his own joy at these versions. In his foreword to Crawford’s book he writes, ‘Latin was one of Scotland’s literary languages for centuries, and the reawakening of its neglected or forgotten European spirit is the task Robert Crawford gives himself in this remarkable, thought-provoking book. Task is perhaps the wrong term to employ of a work which has been compiled with so much gusto, taking many risks and offering the modern reader so many surprises.’

Without the requirement to be slavishly faithful to the original, Crawford’s versions demonstrate that it is possible to make the old new again. Pedants and Latin bores will not be disappointed by some of the liberties that Crawford has taken, and because this is a bilingual edition they will be able to compare his versions with the originals that appear on facing pages. But let them fall on their pens!

The selection from Buchanan includes the ‘Epithalamium for Francois of Valois and Mary Stuart, Monarchs of France and Scotland’ (of his own prose translation of this poem, MacDiarmid was to say that it ‘should certainly be known by heart by every Scottish child’); and a startling ‘Elegy for Jean Calvin’ in which Buchanan fervently desires for Calvin’s Roman detractors a fate far worse than the traditional Christian Hell ever promised. The poems and extracts from Buchanan’s ‘Beleago’ series refer to the time he spent in Portugal, at the University of Coimbra, where he was ‘confined and interrogated by the Inquisition.’ Convinced that he had been ‘grassed-up’ by his dislikeable colleague Belchior Beleago, Buchanan displays in these pieces something greater and deadlier than mere invective. Crawford must have had much fun in making his version of Buchanan’s litany of praise:

‘cretinous, silly-git, syllogist, philosobutcher, Zeno of Lard,/Exhibitionist, inquisitionist…/Throatslitter, nestshitter, brainquitter, inkspitter, Grand/Inquisitor’s Portuguese…Supergrass who grassed/Me up, got me arrested, tested, tortured, chucked/In prison.’

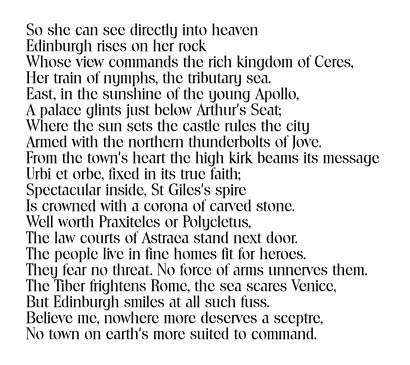

Edwin Morgan notes that ‘Johnston is a gentler soul that Buchanan’: this is readily seen in his poems in praise of Scottish towns and cities and in some of his occasional pieces. His celebration of Edinburgh has to be quoted in full, although it perhaps takes the notion of civic pride a touch too far:

Crawford’s book also has an indispensable and generously long introduction that gives bio-critical studies of his two poets – for who but the scholars know much about these poets? – as well as a short but powerful polemic deploring the fact that Latin has all but disappeared from the school curriculum. The reasons for the demise of this literary language Crawford describes as part cultural, part social and part political. In an ideal world, Crawford’s plea for some kind of restoration of Latin would be heard by the senior policy-makers within the Education and Training Department of the Executive and HM Inspectorate of Education. Fat chance of that, though. Very tellingly, Crawford points out that even during the Reformation, as a literary medium, Latin continued to be used ‘vigorously and even viciously’ by some of the Protestant Reformers, and by none more eloquent than Buchanan. ‘But,’ he adds, ‘you need some access to Latin education to appreciate that.’ If I were to rehearse here all of Crawford’s persuasive arguments, you would not need to buy the book to read his passionate essay. But then you would also be deprived of experiencing his engaging versions of Buchanan and Johnston. And that would never do. Buy Crawford’s book: be open to the arguments in his essay and enjoy the vitality, vigour and inventiveness of his versions of the poems.

© Michael Lister 2006

Apollos of the North. Selected Poems of George Buchanan and Arthur Johnston, edited by Robert Crawford, is available from Polygon (ISBN 1904598811 PBK £14.99).

Comments