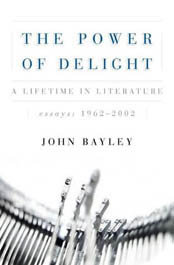

The Power of Delight

The Power of Delight

‘A learned, indeed an erudite book; but also one that is so absorbing, so readable, so quietly and deftly humorous, that it shows up all the dull pretentiousness of the stuff that gets written nowadays about English literature’. This is what John Bayley said about John Sutherland’s Is Heathcliff a Murderer? Puzzles in Nineteenth-Century Fiction in his review in the London Review of Books in 1996. In many ways, this single sentence pretty much sums up Bayley’s own most appealing The Power of Delight.

‘A learned, indeed an erudite book; but also one that is so absorbing, so readable, so quietly and deftly humorous, that it shows up all the dull pretentiousness of the stuff that gets written nowadays about English literature’. This is what John Bayley said about John Sutherland’s Is Heathcliff a Murderer? Puzzles in Nineteenth-Century Fiction in his review in the London Review of Books in 1996. In many ways, this single sentence pretty much sums up Bayley’s own most appealing The Power of Delight.

Lexico-semantic arguments aside, when is an essay not an essay? When it is a review by Professor John Bayley. These reviews – most of which first appeared in the New York Review of Books and the London Review of Books – cover an extraordinarily wide range of works and are insightful, provocative and on occasion startlingly original pieces of criticism. An important critic who has published widely on the English and the Russian Novel and has written a history of the short story, Bayley is probably better-known beyond the academic world for his recent writings about Iris Murdoch: Elegy for Iris, Iris and her Friends and The Widower’s House. These essay-reviews however put Bayley back in the frame as a critic and demonstrate his critical writing to better advantage. It is perhaps the range of his literary sympathies that is most impressive, and not un-naturally he writes best when he is engaged with his subject. Divided into eight sections – ‘English Literature’, ‘The English Poets’, ‘Mother Russia’, ‘American Poetry’, ‘Out of Eastern Europe’, ‘Aspects of Novels’, ‘Correspondences’, and ‘How It Strikes a Contemporary’, this collection constitutes a survey of world literature, almost.

Perhaps unusually for a university professor of English literature, Bayley leaves aside his expected stock-in-trade, and in presenting his arguments does not adopt any high-falutin’ or obfuscating jargon that belongs to current critical theories. He writes clearly and effortlessly and communicates insightful thought after insightful thought.

In his Introduction to the collection, and reviewing his own reviews of the last forty years (Bayley is no mathematician and turns forty years into fifty!), he asks ‘whether the piece would make me want to read again the book or author I had once reviewed. Very often I found I did want to; and I began to wonder whether that wasn’t, perhaps, the most valuable service a critic could render: not only inspiring a member of the reading public to read the book, but to persuade some of them to read it again’. This in itself is a good criterion for helping to establish what is the point of a review, as well as what is the point of a critic. Bayley adds, ‘every reviewer knows that of the work he produces over as span of fifty (ie forty!) years or more very little will deserve to see the light of day again, and of that little he is in luck if some of it actually does get reprinted’. Ensuring that some of Bayley’s work does see the light of day again, this thoughtful selection of reviews has been made by Leo Carey, one of the editors at the New Yorker.

Eminently readable and rewardingly so, each of Bayley’s reviews has some deeply perceptive comments to offer. ‘Best and Worst’, for example, is a review of Fred Kaplan’s 1989 Dickens: A Biography. Here Bayley reminds us just how disconcerting and contradictory Dickens’s genius is. But genius is genius is genius. Bayley delights in making an aside about Dickens’s cannibalism in Bleak House, crediting Kaplan for the observation that Dickens nowhere else mentions cannibalism so directly, though he chastises him for not referring it ‘specifically to the energies and spirit of the novel.’ The suggestion alone of cannibalism is enough. And it is with such helplessness that Bayley in the same piece feels the urge to take a swipe at ‘those two formidable critical lawgivers of Cambridge, England, Dr and Mrs Leavis’. But he does not spend too much time on the dismissive Leavises and returns soon to Dickens, shrewdly concluding that, ‘being a literary genius was for Dickens both the best of fates, and the worst of them.’ Here Bayley is doing more than simply providing a review of Kaplan’s study of Dickens; he is also mediating his own thoughts about one writer writing about another, while bringing himself and his own understanding of and relationship with Dickens to the piece. Quoting Anthony Powell’s ‘a writer writes what he is,’ Bayley adds this is ‘as true of a critic as of a novelist or poet’.

Bayley writes authoritatively and generously about the writings of PG Wodehouse, Philip Larkin, George Orwell, Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, Jane Austen, Sterne, Rupert Brooke, WH Auden, the Russian Novel, American Poetry from Whitman to Ashbery, Byron, Barthes and JM Coetzee, William Golding, Bruce Chatwin, Edward Said, and Gore Vidal. Of those writers he might have missed had he not been asked for a review, Bayley says that ‘doing a review brought us together’. The Power of Delight does indeed bring reviewer and writer together, and reviewer and reader.

The Power of Delight: a lifetime in literature – essays: 1962-2002 by John Bayley is available from Duckworth Publishers (ISBN 0715633120 £25 HBK).

© Michael Lister 2005

AMAZON_SIDEBAR_TEXT <0715633120> <Buy The Power of Delight>

Comments