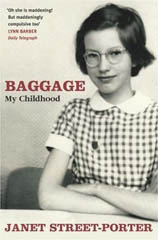

Janet Street-Porter

Baggage

The stork, like the Post Office, can get it wrong. Throughout her childhood, Janet Bull was convinced that she must have been delivered to the wrong address, enduring this outrageous travesty of natural justice in a state of chronic resentment. Her contempt for her family knew no bounds. To confirm her perception of her own innate superiority, she took to counting her talents the way some people count their blessings, seeking confirmation from school reports and Girl Guide badges that she was, indeed, the bee’s knees. After twenty years of this tick-box existence, she launched a venomous salvo at her hapless mother and quit the stultifying confines of the family to seek her fortune in swinging London. The in-your-face phenomenon known as Janet Street-Porter was born.

The stork, like the Post Office, can get it wrong. Throughout her childhood, Janet Bull was convinced that she must have been delivered to the wrong address, enduring this outrageous travesty of natural justice in a state of chronic resentment. Her contempt for her family knew no bounds. To confirm her perception of her own innate superiority, she took to counting her talents the way some people count their blessings, seeking confirmation from school reports and Girl Guide badges that she was, indeed, the bee’s knees. After twenty years of this tick-box existence, she launched a venomous salvo at her hapless mother and quit the stultifying confines of the family to seek her fortune in swinging London. The in-your-face phenomenon known as Janet Street-Porter was born.

Street-Porter’s one-woman show All the Rage, a hit at last year’s Edinburgh Festival, was conceived on the cusp of depression after the breakdown of a relationship. Neil Tennant of the Pet Shop Boys, a close friend, suggested she might convert angst into entertainment. Competitive to the marrow, she rose to the challenge and proceeded to string together chain-saw verbals for her stage rant, incorporating various husbands, work colleagues and her mother as prime targets. With All the Rage on tour, she has now produced Baggage: My Childhood, an autobiography looking at her early life.

It opens promisingly enough. Her parents, Cherrie and Stan, no strangers to the sexual freedoms of wartime Britain, meet at a dance in the summer of 1942. Although both are already married to other people, they embark on a ‘tempestuous relationship’ in which ‘what wasn’t said was more important than what was’. For Cherrie it meant permanent escape from the privations of the tiny stone cottage in North Wales where she was raised. The couple stuck together and in December 1946 along came Janet. It took a further seven years to legalise their union. As their eagle-eyed daughter would observe, the display of wedding photos that signalled respectability in every other household was, in hers, conspicuous by its absence.

The mortgage of £4 a week on a terraced house in Fulham was too steep for her father’s salary as an electrical engineer and so the top two floors, including the inside toilet, were let to a bus driver and his family. This meant that the Bulls had to use the outside lavatory and wash in the scullery, much to Janet’s umbrage. Cherrie’s best friend Eileen also became a paying guest but Cherrie, eight months pregnant with her second child, discovered her in a compromising position with Stan and showed her the door. Cherrie’s younger sister Violet was wrenched out of school and drafted in as a substitute, her potential career casually sacrificed in the service of domestic harmony. However, the arrangement seems to have been congenial. The sisters could chat away together in Welsh, enjoying a privacy denied the rest of the household. Even the budgie spoke Welsh, unlike Janet, who felt even more alienated than usual on family holidays in her mother’s home village of Llanfairfechan.

Stan Bull made no secret of the fact that he would have preferred sons. Generally reserved, he asserted his position as head of the household in table-thumping, martinet moments. Keeping up appearances involved insisting that his wife should wear a spotless white apron when serving food, even on picnics.

It came as a bombshell to the teenage daughters that they were all moving to Perivale, an anonymous London suburb. They had no say in the matter. This triumph of the philistines still gets to Street-Porter. She actually seems to believe that the experiences she enumerates with such wounded astonishment were uniquely awful. It was all so unfair, she is constantly saying. The hypocrisies of her parents may have been legion, but they were bog standard for the time. Far from being ‘extraordinarily bizarre’, her childhood milieu was unexceptional.

Abortions, rebellions, boys and bands dominate her late teens. Nifty with a sewing machine, she runs up trendy little numbers to sell through boutiques and becomes a face on London’s happening scene. On meeting her future husband, Tim Street-Porter, she dumps the previous model with the ruthless single-mindedness that will fuel the rise and rise of the mouf of yoof. By 1988 she was BBC Head of Youth and Entertainment Features, and is now Editor at Large for the Independent on Sunday.

Street-Porter confesses to having a low boredom threshold. She makes no concessions to that possibility in her readers. In the flesh she comes over as forthright, resilient and entertaining but on the pages of this memoir she is petulant, vulnerable and tediously point-scoring. Despite the Ortenesque material to hand, large tracts are dull as ditch water, although we are left in no doubt that in her own fine opinion of herself she is unremittingly amusing and ironic. Janet Street-Porter is an unabashedly self-made and self-promoting baggage. Goodness has nothing to do with it.

Review of Baggage: My Childhood by Janet Street-Porter. This article originally appeared in the Sunday Herald.

Copyright Jennie Renton 2004

Comments