Eric Dickson

Inflamed by Sparks

Muriel Spark is one of the most collectable of contemporary writers. Critical studies, essays, poems, novels, short stories – all glitter with her signature wit and energy. At the age of eighty-five her powers are undiminished and she is working on an eagerly anticipated novel. New York publisher New Directions is preparing to issue her collected poems next year and the Paris publisher La Table Ronde has plans for a bilingual edition of her selected poems. Appreciation of her work is reflected in the blossoming success of the Muriel Spark Society.

Right: Michael Ayrton’s specially commissioned etching for the Observer Books 1971 limited edition of Not to Disturb.

Right: Michael Ayrton’s specially commissioned etching for the Observer Books 1971 limited edition of Not to Disturb.

In 1933 messrs Millar and Burden of Leith published a penny broadside, the result of a poetry competition to mark the 100th anniversary of the death of Sir Walter Scott. The winning poem was by a fifteen-year-old pupil of James Gillespie’s School for Girls. How apt that Muriel Spark, who has always considered herself a poet, should have this as her first published work. It is an extreme rarity – the only copy in a public collection is in St Louis, Missouri.

In 1951, the Observer held a short story competition on the subject of Christmas. Muriel Spark entered ‘The Seraph and the Zambesi’; she has spoken movingly of how she almost had to beg for paper on which to type her story. It is a great thrill for me to own a copy of its only separate publication, by the American publisher, Lippincott. The £250 prize money was a godsend for Spark, but times would remain hard for her for some while yet. Graham Greene, however, was a great support. At his Memorial Requiem Mass at Westminster Cathedral in 1991, Spark gave a moving address in which she recalled:

My debt to him is personal as well as cultural. In the mid-1950s I was a comparatively unknown writer in very difficult circumstances. In those days there were no grants and very few prizes. We were out there on our own. Graham Greene who had read some of my stories heard at third hand of my predicament and offered of his own accord to support me until I had managed to make enough to live on. This encouragement, his faith in my possibilities and his material support meant an enormous amount to my efforts to write a first novel. How proud I was to be his protegée. It was typical of Graham that with the monthly cheque he often sent a few bottles of red wine to take the edge off cold charity. I finished the novel and had it published.

The novel was The Comforters and the year 1957. Then, it would have set you back 13s 6d. Its ‘first novel’ status makes it particularly desirable to collectors and it now sells for as much as £800. I don’t yet have a copy myself. Nor one of Reassessment, originally priced at 6d; I recently saw it offered for sale at £775. I would particularly love to have this 1948 pamphlet, because it was the first publication to carry the name of Muriel Spark, and as such it is a piece of literary history. There is a certain, not uncommon, irony in the fact that her most famous novel, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, fetches a comparatively modest £100-£150. The Comforters had a print run of just over 3000, while Brodie‘s was more than five times that number. (To put these figures into perspective, over 1.7 million copies of Spark’s books have been sold by Penguin alone.) With the publication of The Comforters, Spark began an association with Macmillan that would last for more than twenty years, until 1979 and the publication of Territorial Rights. The Spark/Macmillan papers in the National Library of Scotland demonstrate the publisher’s role in steering the young poet and critic down the road of the novel.

John Alcorn’s jacket design for Territorial Rights (Macmillan, 1979) signals the novel’s Venetian setting.

John Alcorn’s jacket design for Territorial Rights (Macmillan, 1979) signals the novel’s Venetian setting.

The dust wrappers of Spark’s early books, designed by artists such as Victor Reinganum and Hal Siegel, burst with colour and vigour. I can see how they tempted readers back in the 1950s and ’60s. The dust wrapper on my first edition of The Girls of Slender Means carries contemporary tributes:W.H. Auden wrote, ‘I find Miss Spark’s novels beautifully executed… she seems to know exactly what she is doing… funny, moving, and like nobody else’s.’ Praising her ‘penetrating imagination,’ Evelyn Waugh called her ‘the only living exponent of the uncanny (save Mr Greene in a rare mood).’

The different author portraits publishers used constitute a kind of mini-biography in themselves. On the lower panel of The Girls of Slender Means, Spark looks intently into the future. By the 1960s and The Driver’s Seat, Spark sits by a fountain in dolce vita Rome in an elegant black dress. In the American edition of The Abbess of Crewe she gazes dreamily out the window of a Tuscan farmhouse. By the 1980s and A Far Cry from Kensington, we see an image of a poised, assured author, established on the world stage.

The first US edition of The Girls of Slender Means (Knopf, 1963) carries W.H. Auden’s tribute to Spark’s “beautifully executed” novels on the front of the dust wrapper; on the back, reviews include John Updike’s comment that “detachment is the genius of her fiction.”

The first US edition of The Girls of Slender Means (Knopf, 1963) carries W.H. Auden’s tribute to Spark’s “beautifully executed” novels on the front of the dust wrapper; on the back, reviews include John Updike’s comment that “detachment is the genius of her fiction.”

I sometimes despair of much contemporary book production. The earlier Spark books are from an era when higher standards prevailed:printed well, on non-acidic paper, they are destined to outlive many books produced decades after them. Booksellers have developed their own technical jargon to describe the idiosyncrasies conferred on books by the passage of time. Sometimes I amuse myself by applying this argot to myself:’slightly sunned’, or ‘rare in this condition’. (In reality, the epithets ‘slight spine lean’ or ‘frayed at the edges’ might be more appropriate.) The reflection in my computer monitor confirms that I possess a few nicks and tears of my own!

I couldn’t have built my collection of Spark first editions without the internet. Items have come from as far afield as Elvaston (Illinois), Albany (CA), New York and London. I picked up my excellent copy of The Girls of Slender Means in Alnwick, Northumberland. So far, not one of my first editions, not even Brodie, has come from an Edinburgh bookseller.

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (Macmillan, 1961), Spark’s most famous book, which she sometimes refers to as her “old milch cow.”

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (Macmillan, 1961), Spark’s most famous book, which she sometimes refers to as her “old milch cow.”

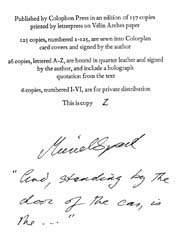

Limited editions have their own special pleasures. I regard the Colophon Press edition of 111 Years Without a Chauffeur as a work of art. Printed on hand-made, cream wove paper, bound in quarter calf, its spine embossed in gold and with a stitched binding, it shows that the bookbinders’ craft remains alive and well, at least in some small publishing houses! This book is a sensual object, a delight to touch, hold and smell. When I hold it, I am aware that Muriel Spark herself has held it:she has not only signed it, she has provided a holograph quotation from the text. 111 Years Without a Chauffeur is a jewel of a story. I first read it before publication in book form, when it appeared both in the Scotsman and the New Yorker. When I heard there was going to be a limited edition, each with a different holograph, I immediately decided to go for the last copy in the series in the hope that the tale’s moral sting would be the one I would receive. Luckily, this proved to be the case.

I also have the Colophon edition of The French Window and The Small Telephone, two children’s stories; as far as I know, this was their only publication in book form. I found on the internet The Very Fine Clock, another story for children, and was very keen to acquire it until the bookseller mentioned the crayon markings on some pages. I took a rain check.

I also have the Colophon edition of The French Window and The Small Telephone, two children’s stories; as far as I know, this was their only publication in book form. I found on the internet The Very Fine Clock, another story for children, and was very keen to acquire it until the bookseller mentioned the crayon markings on some pages. I took a rain check.

In 1971 Observer Books published an edition limited to 500 deluxe copies of Not to Disturb, containing a specially commissioned print by Michael Ayrton. For me, it is a unique pleasure to see Ayrton’s and Spark’s signatures side by side. Limited editions also give me the chance to have some fun with numbers. For example, I managed to buy copy no. 111 of… yes, you’ve already guessed. And when a friend and fellow member of the Muriel Spark Society recently reached the age at which life begins, I bought him copy No. 40.

Left: Muriel Spark’s autobiography, Curriculum Vitae (Constable, 1992) covers events up to 1957 and the publication of her first novel, The Comforters. Celebrating its positive reception by critics, her agent Alan Maclean expressed the belief that this would be the shape of things to come. Spark concludes her autobiography with the now famous words, “I took great heart from what he said, and went on my way rejoicing.”

Left: Muriel Spark’s autobiography, Curriculum Vitae (Constable, 1992) covers events up to 1957 and the publication of her first novel, The Comforters. Celebrating its positive reception by critics, her agent Alan Maclean expressed the belief that this would be the shape of things to come. Spark concludes her autobiography with the now famous words, “I took great heart from what he said, and went on my way rejoicing.”

My American Franklin Library copy of The Only Problem is signed by Spark and it has a two-page introduction by her which is unique to this edition. In it she speaks of her friend, the critic Allen Tate, and his view that the best novels and stories aspire to the condition of poetry. She states that this is the criterion by which her work should be judged.

One book in my collection, rather like its author, has had a rather intriguing international genesis:The Portobello Road and Other Stories, published in 1990 by Eurographica Press in Helsinki, Finland and printed on Michelangelo paper at the Magnani Paper Mills in Pescia, Italy. I have No. 217 of 350 copies signed by the author. I work at the National Library of Scotland and when I realised that it did not have a copy, I wasn’t sure quite who to alert. The international buyer? The Scottish buyer? Or perhaps Rare Books?

In The Mandelbaum Gate (Macmillan, 1965), the complicated dichotomies of the divided city of Jerusalem parallel those of Barbara Vaughan, who is half English and half Jewish.

In The Mandelbaum Gate (Macmillan, 1965), the complicated dichotomies of the divided city of Jerusalem parallel those of Barbara Vaughan, who is half English and half Jewish.

An area of collecting I recently broached is that of the inscribed copy:books with a dedication from Spark. Some do come onto the market, but certainly not many. When offered an American edition of The Mandelbaum Gate inscribed by Spark to her American agent Dorothy Olding, I was sorely tempted. But would I be invading private space? In the end I took Oscar Wilde’s advice, that the way to deal with temptation is to succumb to it.

The above reflections remind me of a proverb that could almost have come from Spark’s own pen: ‘What you own ends up owning you.’ In collecting books by Muriel Spark I can do no other than ignore that warning, for I am more than happy to be possessed by these works – by their life, their humour and their humanity.

Copyright Eric Dickson 2005.

Comments