needlework

Fashionable Reading

‘To know the history of embroidery is to know the history of women’ says Rozsika Parker in The Subversive Stitch. Embroidery and the making of the feminine. Aldyth Cadoux, teacher of Russian and collector of needlework books agrees.

‘To know the history of embroidery is to know the history of women’ says Rozsika Parker in The Subversive Stitch. Embroidery and the making of the feminine. Aldyth Cadoux, teacher of Russian and collector of needlework books agrees.

It’s only recently that there has really been an interest in the sub-culture of women. Women’s interests have always been wide-ranging, even when they have been confined to the domestic sphere. I think that women tend to have a more subtle approach to most subjects than men.

I inherited my love of needlework from my mother. If she had been born nowadays she would probably be working in a museum as a restorer of textiles. Modestly, she would have called what she did darning.

I’m particularly fascinated by the sort of life led by the person I might have been if I had been born 150 years ago, part of the new middle class rather than of the gentry. The sort of life that Dickens shows in David Copperfield. Think of David Copperfield’s first wife, Dora Spenlow, who, poor dear, didn’t know how to cook, she was brought up so genteelly. Even not very prosperous middle class households would have some servants, not necessarily good servants, to keep up appearances. The clothes women wore were hardly geared to sensible lives. Tight corsetting didn’t do a lot for your insides. Many women died in childbirth. Women usually had a separate life from men. They still do.

To the books.

‘You might call my collection Best Squirrell.

I have about all of Jane Gaugain’s books on Knitting, Netting and Knotting which heralded the arrival in the drawing room of these traditionally peasant pursuits. Her books weren’t cheap, and it’s evident from her subscription lists that wealthier people in Edinburgh, both gentry and middle class, were buying them. She published supplements illustrating how to knit and how to sew in the new, delicate way instead of the country, efficient way. Tatting and crochet also became tremendously popular as ways of showing off a lady’s hands. I have an oil painting of a lady doing crochet, so painted that the very centre of the picture shows her hands.

The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine was the first ever cheap magazine for women to include fashion plates and inserts of paper patterns. It was started by Sam Beeton, Isabella Beeton’s husband, an entrepreneur publisher. I have a few separate copies of the original magazines (including inserts). It first appeared in 1852 at twopence a copy. I prefer these individual issues to bound volumes. Having them in their original state, you see how people saw them when they were first purchased. The magazine was aimed at a thinking, literate public, and by the 1860s dealt openly with controversial issues, notably women’s rights.’

It was a radical departure from the usual run of fashion journals of the period such as The New Monthly Belle Assemblee, which were aimed at the well-to-do. Their main attraction was hand-coloured engravings illustrating the latest Paris fashions; articles were typically prudish, vapid and sentimental. The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine courted a different readership. Under Sam Beeton’s editorship, the tone of the articles was determinedly thought-provoking. Until the 1860s he had to muzzle direct statement of his unacceptably progressive views on the rights of women, though, even in the early days, he dealt acerbic critical comment on issues like the inadequacy of girls’ education, which was no more than a training for decorative uselessness. (Obviously, little of this applied to working class women).

The magazine regularly included features on cookery, dressmaking, child-care, gardening and family medicine. In addition, there were a number of serialisations of books by contemporary writers, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Wilkie Collins among them, and a monthly essay competition for readers; one subject set, perhaps in an attempt to break the rather staid monotony of readers’ offerings, was, ‘Do Married Rakes Make the Best Husbands?’

But it was perhaps the dressmaking feature, with the innovative inclusion of diagrams for the home dressmaker, which clinched the popularity of the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine with a readership who couldn’t afford to buy their clothes from Paris couturiers.

In 1860, after the death of her first child, Isabella started to write fashion features for the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, and to collaborate with Sam on its redesign. They made a business trip to Paris to establish an arrangement to receive from M. and Mme. Goubaud, who ran Le Moniteur de la Mode, detailed descriptions of the latest Paris fashions and coloured fashion plates (hand-coloured by girls, each assigned a different colour to fill in). The result was a larger, more glamorous production that sported coloured fashion plates and needlework patterns, at the higher price of 6d. A full-size paper pattern, ready tacked, could be ordered for 3s 6d for any of the styles illustrated in the plates. Individual copies, complete with inserts and plates are scarce as the proverbial hen’s tooth.

‘Dressmaking patterns were all tried out by Isabella and her sister on the drawingroom floor. Can you imagine them down on their knees in their crinolines? The new style magazine went from strength to strength.

Madame Riego de la Branchardiere was a contemporary of Mrs. Beeton. Another marvellous woman. I have a complete volume of her publication The Needle, 1854. She was an amazing woman. She had a very enhanced view of her own importance. For instance, in one issue she writes, To a constant subsubscriber. A reference to the Government Gazette Official Catalogue or the List published in the newspaper of 1851 will convince you that the statement of my being the only one who received the prize medal for crocheting point is correct. In the exhibition, nearly all the exhibitors of this description of needlework did me the honour to use my designs, and some have since asserted that they have the prize. But there are unprincipled persons in all professions. I should not have deemed it necessary to contradict their assertions if my veracity had not been called in question.

Madame Riego de la Branchardiere was a contemporary of Mrs. Beeton. Another marvellous woman. I have a complete volume of her publication The Needle, 1854. She was an amazing woman. She had a very enhanced view of her own importance. For instance, in one issue she writes, To a constant subsubscriber. A reference to the Government Gazette Official Catalogue or the List published in the newspaper of 1851 will convince you that the statement of my being the only one who received the prize medal for crocheting point is correct. In the exhibition, nearly all the exhibitors of this description of needlework did me the honour to use my designs, and some have since asserted that they have the prize. But there are unprincipled persons in all professions. I should not have deemed it necessary to contradict their assertions if my veracity had not been called in question.

I do like having the original numbers. The adverts show what people were buying at the time. But I only have one original of The Needle. I have several other magazines devoted to fashion, often with hand coloured plates. The Courier Dedans, a French magazine. The Supplement to The Young Ladies Journal. And inside, of course, the actual patterns. Look at the pretty plates. Women lost a lot when they cut inches off the bottom of their skirts!

Aldyth’s collection includes all sorts of items of ephemera.

The sewing machine was invented in 1845 by an American, Elias Howe. Here is the Howe Exhibition Catalogue. The cover, front and back, is printed in colour and gold by Kronheim & Co., 9 Dey Street, New York. From the introduction we learn Elias Howe was: Born at Spencer Mass., in 1819, his early years were spent in toil as the son on an humble farmer and miller, and at the age of 19 years we find him learning the trade of a machinist in a shop in Boston, when he overheard a conversation in which the remark was made: ‘Invent a Sewing Machine, and I will assure you an independent fortune.’ He commenced to reflect upon the art of sewing, to watch the process, as performed by hand, and to wonder whether it could be accomplished by machinery….

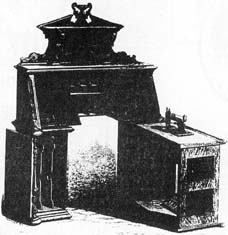

All the early machines were small. But before long, they were making magnificent ‘sewing machine cabinet and secretary combined’, very similar to things you find in the latest sewing machine catalogues. It’s odd how things come round again.

All the early machines were small. But before long, they were making magnificent ‘sewing machine cabinet and secretary combined’, very similar to things you find in the latest sewing machine catalogues. It’s odd how things come round again.

I have some examples of books teaching dressmaking to the poor. Here is an early nineteenth century book, Instructions for Cutting out Apparell for the Poor. Principally intended for the assistance for the patronesses of the Sunday Schools and other charitable institutions but useful in all families, containing patterns, directions and calculations whereby the most inexperienced may readily buy the materials, cut out and value each article of clothing of every size without the least difficulty and with the greatest exactness. With a preface containing a plan for assisting the parents of poor children belonging to Sunday schools to clothe them and other useful observations – published by the benefit of the Sunday School children at Hertingfordbury, County of Hertford.

What I would like to do is look at the development of the teaching of needlework. Here is a book published in1816 by the British and Foreign School Society which contains absolutely lovely specimens of needlework. The System of Teaching Reading, Writing, Arithmetic and Needlework. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, embroidery went out and then came in again as a subject to be taught in schools in the 1920s. I’d love to go through the history of its disappearance, when it stopped, and then it’s re-introduction. In Scotland, Ann MacBeth played an important part in this process. The book that demonstrates her approach is Educational Needlecraft by Margaret Swanson and Ann MacBeath. Glasgow School of Art, 1925.

Rozsika Parker recounts that Jessie Newbery, who was responsible for embroidery at the Glasgow School of Art between 1894 and 1908, did much to hasten the re-evaluation of embroidery ‘as an art with a history that determines but need not limit its practice…around1900 the Scottish Education Department made embroidery an important part of the normal school curriculum, and the Glasgow classes were opened to women teachers from the city and throughout the West of Scotland. Ann MacBeth who had studied at the Royal School of Needlework was put in charge of classes. She developed a way of teaching the art which still forms the basis of contemporary embroidery instruction.

If Jessie Newbery loosened the hold of femininity on embroidery, Ann MacBeth could be said to have undermined its class connections. The siks and satins of Art needlework were abandoned in favour of cheaper fabrics. Her basic principle was that the design should arise out of the technique employed.’

‘Another thread of my book collection is on travel in Uzbekistan and anything about the embroideries of the region. Uzbek embroideries have links with Indian embroideries. One tends to think of the silk roads going East and West but they also ran North and South, through Bukhara, through Samarkand, South into India. From what I’ve read about the trade caravans, the cities of Uzbekistan sound like Piccadilly Circus in the rush hour. You feel that at times they needed a very good traffic controller to tell the camels which way to go. All trade was done by camel caravan.

‘Another thread of my book collection is on travel in Uzbekistan and anything about the embroideries of the region. Uzbek embroideries have links with Indian embroideries. One tends to think of the silk roads going East and West but they also ran North and South, through Bukhara, through Samarkand, South into India. From what I’ve read about the trade caravans, the cities of Uzbekistan sound like Piccadilly Circus in the rush hour. You feel that at times they needed a very good traffic controller to tell the camels which way to go. All trade was done by camel caravan.

I am extremely interested in the women embroiderers of 19th century Uzbekistan, groups of whom embroidered enormous hangings – 2.5 x 2 metres. Each one took over two years to complete. What I like about them is that they are domestic. They are not ‘important’, like the rugs. They are what the local people used in the home. I refuse to believe they were done for mere decoration. You don’t work for two years of your life, particularly when your life expectancy is only about 40 years at most, for pure decoration. I think they had various significances. As well as being ornamental they were symbolic and talismanic. They had medicinal significance. They were to remind you what granny used to use when the baby was ill and so on. The majority had embroidered floral patterns – flowers that were medicinal. The huge poppies represented opium, a very important medicinal drug in those days.

These embroidered hangings were traditionally used as bridal sheets as part of the dowry, but were also used to cover the corpse of the girl if she died between being affianced and finally married, not uncommon. Life was tough for the Uzbeks. The Burrell Collection has about ten of these hangings which will be put on show in two years time. The Curator of Textiles has asked me to contribute an essay on their collection of Uzbek Textiles which are known as Bukharan embroideries to the antiques trade. Funnily enough, I’m probably better known in Russia for my knowledge of Uzbek embroideries than I am in Britain.

The Subversive Stitch, Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine by Rozsika Parker, The Women’s Press, 1984.

Copyright Jennie Renton, Photograph Copyright Allan Stewart

Comments