Scottish Nationalist

Designing Woman

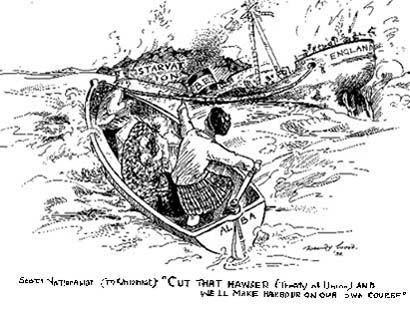

Wendy Wood understood the power of popular communication in art and in the press. Her reputation, however, lies in her political role, primarily as a Scottish Nationalist. She was an agitator, a lawbreaker who was spurred to direct action over sensitive issues such as national identity and nuclear energy. However, she asserted that as an artist she was not a propagandist and that she had ‘only painted one picture with patriotism as its subject’. With hindsight, her division of art and politics may have been a tactical form of self-preservation.

Wendy Wood understood the power of popular communication in art and in the press. Her reputation, however, lies in her political role, primarily as a Scottish Nationalist. She was an agitator, a lawbreaker who was spurred to direct action over sensitive issues such as national identity and nuclear energy. However, she asserted that as an artist she was not a propagandist and that she had ‘only painted one picture with patriotism as its subject’. With hindsight, her division of art and politics may have been a tactical form of self-preservation.

Wood was adept at using her visual imagination. At public meetings, some more turbulent than others, flags, badges, banners and road signs were used to great effect. Some of her political escapades were pure performance art: subversive, anti-authoritarian, irreverent and humorous in the tradition of pageants of chaos and carnivalesque.

Wendy Wood adopted her mother’s maiden name in 1927. Her birth name was Gwendoline Meacham. She was born in Maidstone on 29 October 1892 and the family moved to Cape Town, South Africa in 1894. If challenged as to her Scottish birthright, she would reply, ‘One does not have to be a horse to be born in a stable.’

Both parents were amateur artists. Her mother, descended from the Ross clan, told her Scottish cradle tales that included the adventures of William Wallace. Each Sunday afternoon the Meacham children saw slides of Scotland taken by their father, a research chemist and a founder of the South African Society of Artists. They were encouraged to think of Scotland as ‘home’. Wood noted that, from childhood, she ‘cared for little but art’. At the age of five years, she wrote her first poem ‘To my Mouce’; at seven, she met Rudyard Kipling; and when she was nine she produced an illustrated version of The Further Adventures of Sexton Blake with her brother. During the Boer War her father gave her a miniature rifle to defend herself; she must have been keenly aware of the distinctly different views about political and territorial rights held by British, Dutch and indigenous African constituencies.

But it was art that continued to matter most… Of her time as a pupil at Hamilton House secondary school in Tunbridge Wells, she wrote:

But it was art that continued to matter most… Of her time as a pupil at Hamilton House secondary school in Tunbridge Wells, she wrote:

It was to draw and paint that I rose at six on winter mornings and stole on tiptoe to the cold school studio to work in secret… Drawing filled every margin of my exercise books, painting filled every second of my spare time…

Holidays at Kippford near Dumfries in a house designed by her father inspired some of her early illustrations, which include narratives about boats and the sea. Figures in the landscapes indicate her interest in folk and fairy legends and the magic realism of fantasy worlds of nature as well as the enchantment of childhood. Art historian Elizabeth Cumming has discussed the connection between late Victorian Scottish Arts and Crafts practitioners and the environmental concerns of Patrick Geddes as a project of social and aesthetic reform. Such aesthetics formed a potent connection between nature and the genius loci. This latent relationship between nature and romantic visions of elysian national identity grew slowly but steadily in Wood’s work. On leaving school in 1905 she moved to London where she joined her sisters – one of whom married Irish poet and folklorist Herbert Hughes – and their cosmopolitan friends. She moved in the same circles as Eric Gill and his family, the Morrow brothers (George was an illustrator for Punch), H.G. Wells, G.K. Chesterton, W.B. Yeats and Bernard Shaw. She read Nietzsche, Balzac, de Maupassant, Celtic legends and Omar Khayyam. She enrolled for drawing lessons at Westminster School of Art and also for evening classes from Walter Sickert.

For ten shillings per quarter at the London County Council one could be taught by one of the greatest masters, that is to say, the pupils could enrol, but if for any reason Sickert did not approve of them, somehow they did not turn up again. I was a lot younger than the other students. It was my first experience of a life class and I was terribly nervous of the great man… Sickert took my pencil from me, also my India rubber which he threw out of the window… Everyone in the class either fell in love with or loved Sickert or fell foul of him and loathed him.

Sickert encouraged her interest in print and in the traditional discipline of drawing. The legacy of the classes she attended between 1905 and 1909 rooted her work in naturalism and descriptive aspects of balance, proportion, harmony, colour, tone and perspective. In 1907 she approached William Rothenstein, for whom she wanted to work as an assistant. He told her: ‘You’ve got a terrific imagination. I have none. I can’t paint a ribbon without seeing it. I’d curb you and exhaust you in a short time. Keep away from art schools and just keep on drawing and painting.’ She ignored his advice and completed art school training. Sickert complimented her by keeping one of her drawings and signed her passe-partout to European galleries with the word ‘artist’.

Gwen Meacham was the beneficiary of a liberal education in an age of radical social reform. By the age of seventeen she had the credentials of a ‘new woman’, a professional qualification as an artist. But while she ‘believed ardently’ in Votes for Women she also ‘avoided militant action’. At this time she admired Keir Hardie and the Independent Labour Party and believed they could achieve real change. Her practical contribution was to begin nursery nursing in London’s East End. She lost interest in organised religion and stopped drawing ‘fat and happy children’. The hiatus in her practice of drawing and painting lasted several years until well after her marriage in 1913 to Walter Cuthbert, although she designed and worked appliqué for a local shop at 9d an hour. Inhibited to some extent by the strict religious practices of her husband’s family, who were Original Seceders (close to the practices of ‘Wee Free’ Presbyterians), and absorbed by the demands of married life, she became ill and she found that drawing and painting helped restore her health. Her husband added a studio to their home in Ayr. In 1917 she began to look for a niche in the film industry and the following year, although the mother of two young daughters, Cora and Irralee, she founded a documentary film company. However, her initiative with Ayrshire Cinematographic Theatres Limited failed and she suffered further bouts of ill health. Her doctor, who saw her as ‘an artist out of her element’, introduced her to Jessie M. King and her husband E.A. Taylor, who encouraged her to refresh her skills at Glasgow School of Art. They also urged her to join Ayr Sketch Club.

Her confidence grew and in 1923 she produced illustrations and poems for her first book, The Baby in the Glass, for which Jessie M. King wrote the preface. Wood’s line drawings were expressive of the relationship between a mother and her children; they might be called child-centred images and child-like poems. That same year family finances provoked a move to Dundee. There she met kindred spirit, artist and nationalist Stewart Carmichael, who painted her portrait in the same year. She took a job as ‘Auntie Gwen’ on a children’s radio programme broadcast from Dundee and worked as an illustrator for the children’s magazine Little Dots. Her second collection of verse for children, The Chickabiddies Book, appeared in 1927, illustrated with her own line drawings.

In 1927 she made a decisive break from her marriage and from Dundee. That summer she began a fresh account book, which records an extraordinary level of activity. She produced drawings, poems, plays and articles and started moving in new social and artistic circles. She formed a fruitful friendship with William Gordon Burn Murdoch who hosted meetings of artists and writers of the PEN club at his home in Arthur Lodge. There she met David Foggie, a teacher of Drawing and Painting at Edinburgh College of Art, who, as was his habit, asked her to sign the portrait he completed of her in 1932. Through Burn Murdoch she also met Lewis Spence, a linguist, mythologist and folklorist. He persuaded her to join the Scottish National Movement and she supported his campaign as a Nationalist Candidate for North Midlothian in 1929.

Spence wrote the preface to Wood’s first extended prose work, to which she added her own landscape illustrations. The Secret of Spey (1930) was a travel book about the Spey Valley but it was more than a bland travelogue. It reflected Wood’s attachment to nature and her desire to engrave pictures and compose with words. It demonstrated her eye for etiological details of places, names, legends and superstitions. It included Gaelic words and place-names that signified her linguistic identification with Gaelic Scotland. In it she seconded the opinion of Elizabeth Grant of Rothiemurchus, that the concentrated power of faith and fantasy in Highland life was:

Spence wrote the preface to Wood’s first extended prose work, to which she added her own landscape illustrations. The Secret of Spey (1930) was a travel book about the Spey Valley but it was more than a bland travelogue. It reflected Wood’s attachment to nature and her desire to engrave pictures and compose with words. It demonstrated her eye for etiological details of places, names, legends and superstitions. It included Gaelic words and place-names that signified her linguistic identification with Gaelic Scotland. In it she seconded the opinion of Elizabeth Grant of Rothiemurchus, that the concentrated power of faith and fantasy in Highland life was:

a very reasonable mixture surely. For the Daoine Sith are the spirits of the dead, disembodied souls awaiting rebirth. The faerie faith, surviving as it does in Celtic lands… is in line with all other faiths in which angels and spirits hold their place, and only those ignorant of even the little that is known about psychic energy, and those who are blind to the beauty of the Celtic Tradition, will lift the nostril or raise the eyebrow in scorn. The Faeries of Glenmore are only a further illustration of the belief in that something indestructible of which sage and savage have been equally aware…

This is a romantic vision and a celebration of pantheistic forces that draws on nature as a source of descriptive and symbolic meaning. In contrast to The Secret of Spey, A Lad of Dundee (1935) had a completely different function and purpose. This relatively simple storybook published in America, co-written with American author Elizabeth Marion King and illustrated by a Canadian-born artist working in New York, Helene Carter, was a deliberate act on Wood’s part to support the export drive of Scottish goods to the transatlantic market. As such, it gives a somewhat stereotypical view of a family in Dundee as well as the Dundee jute and marmalade industries, Edinburgh and the castle and country life in Scotland. Wood had not yet arranged a formal divorce and the book was published with her married name, Gwen Cuthbert.

Wood was sceptical about the Second World War and remained sceptical about the relationship of Scotland to England. In 1939 she left Edinburgh with Oulith MacAndreis, an editor of Smeddum and allegedly a member of the IRA. Crofting offered an escape from the war and the demands of the city as well as the realisation of a magnificent and romantic dream with her ideal lover in Alt Ruig, their cottage near Glenuig. A 1944 illustration of the Children of Lir shows greater fluidity than previous work and it presages the abstract drawings and paintings that Wood produced after 1960. During the Forties she illustrated and wrote articles about crofting for Chambers’ Magazine, the Edinburgh Evening News, the Evening Dispatch and the Daily Record which were subsequently collected for publication as Mac’s Croft (1946) and Highland Croft (1952) – by which time the relationship with MacAndreis was over. He admitted he was already married and she moved to another croft.

Wood was sceptical about the Second World War and remained sceptical about the relationship of Scotland to England. In 1939 she left Edinburgh with Oulith MacAndreis, an editor of Smeddum and allegedly a member of the IRA. Crofting offered an escape from the war and the demands of the city as well as the realisation of a magnificent and romantic dream with her ideal lover in Alt Ruig, their cottage near Glenuig. A 1944 illustration of the Children of Lir shows greater fluidity than previous work and it presages the abstract drawings and paintings that Wood produced after 1960. During the Forties she illustrated and wrote articles about crofting for Chambers’ Magazine, the Edinburgh Evening News, the Evening Dispatch and the Daily Record which were subsequently collected for publication as Mac’s Croft (1946) and Highland Croft (1952) – by which time the relationship with MacAndreis was over. He admitted he was already married and she moved to another croft.

On 6 August 1949 in Fort William, The Scottish Patriots, an avowedly ‘non-political’ organisation, held their first meeting. Wood was a founder of the organisation and wrote, produced magazines, minted badges and designed stamps to subsidise the cause. Meanwhile, in 1950, what was possibly her most polished and vivid account of Scottish landscape was published: Moidart and Morar contains photographs of the countryside and only two small sketches and endpaper maps by the author. The text is shot through with allusions to art and illustration, and begins with reflections on the role of the artist as portraitist:

In portraying the face of someone with whose mind he is well acquainted, though his survey be as exact, the artist cannot help portraying character and thought within the limning, of which outsiders are unaware. There is some mental exchange, some understanding sympathy passing continually between sitter and painter, that makes his task complex in the nature of a dedication… it is with such familiarity that I approach the writing of a book on this part of the Highlands.

She wrote self-consciously as an artist. Her descriptions of the senses – smells, colours, tastes, sounds, physical forms – are transmitted in the text. She also conveys the qualities of friendship and companionship on her travels. She threads the text with Jacobite adventures. She projects concrete images of the size and scale of sites as well as abstract emotions and atmospheres. At the site of Resipol she noted:

She wrote self-consciously as an artist. Her descriptions of the senses – smells, colours, tastes, sounds, physical forms – are transmitted in the text. She also conveys the qualities of friendship and companionship on her travels. She threads the text with Jacobite adventures. She projects concrete images of the size and scale of sites as well as abstract emotions and atmospheres. At the site of Resipol she noted:

long green heather clung wherever an inch of ledge gave it foothold, and silver threads of shining water filled their length to splash among the broken stones below. Their spray had frozen on the withered grass, encasing it in a glass covering two inches thick. I crouched down and looked at it from ground level… the ice-encrusted grass made a full-size forest containing rainbows and mirrored lights, spears and silver pennants and could my body have accompanied my mind into the faerie land of scintillating lights, I would have been drawing rainbows with every breath.

She used her sense of place and her relationship to Scotland as an extended reflection on nature and art. This almost anatomical relationship with Scotland was a persistent theme in further publications.

Wood continued to campaign, to write and to illustrate her books and she continued to enjoy the company of other artists, often accompanied and supported by her daughters. From 1956 onwards Wendy Wood shared the home of the artists Florence and Agnes St John Cadell. Living with these cousins of the Scottish Colourist F.C.B. Cadell was mutually beneficial: Florence Cadell painted Wood’s portrait in 1959.

A friend since she arrived in Edinburgh in 1927, Compton Mackenzie dedicated his book On Moral Courage to her in 1960. Her second volume of autobiography, Yours Sincerely for Scotland, published in 1970, presaged another phase of TV broadcasting: as a storyteller, she appeared in the children’s programme Jackanory between 1973 and 1979.

Wendy Wood did not appear to connect her own design and art with politics. One might suggest that she kept an ironic and tactical distance between them. But if the term ‘design’ includes a broad concept of plans brought to fruition, then it is worth reconsidering her role. If, as Philip Taylor suggests, ‘propaganda is a process of persuasion and… persuasion is a welcome and necessary means of forging democratic consensus in a civilised world…’, then Wendy Wood used any means at her disposal to propagandise: to propagate her beliefs about Scotland and its need for a Parliament and independent status. The underlying evangelical and practical functions of texts, however humble, linked the practical exercise of design, art and politics. Wood’s ideas spilled out in her illustrations, painting, writing and broadcasting. Her taste for travel, adventure, inquiry and dogmatic criticism may be considered as a parallel to other Scottish artists’ discourses. For her, the processes of inscription were not limited to illustrations and text. The propagandist in Wendy Wood can be seen in a satirical cartoon, a self-image published posthumously in Astronauts and Tinklers in Edinburgh in 1985. Her authorised biographer, Rowena Love, is currently documenting her life with reference to the political and historical context. She remains a controversial figure. Historian Christopher Harvie has commented dismissively that her ‘support of Nationalism was rarely significant’. But Joy Hendry, editor of Chapman and Wood’s literary executor, takes a very different view, contending that Wood was driven by her belief ‘in freedom, of the individual, of the nation’.

The illustrations and photographs accompanying this article are reproduced with the kind permission of the executors of the estate of Wendy Wood; particular thanks to Joy Hendry and Cora Cuthbert.

Copyright Rosemary Addison 2005

Comments