Marjorie McNaughtan

McNaughtan’s Bookshop

I first went into McNaughtan’s Bookshop when I was eight with an aunt who was looking for a copy of Francis Hodgson Burnett’s The Little Princess. I felt as if I had entered a land of precipitous canyons composed of books, and though I longed to touch them, a daunting glance from Mrs McNaughtan curbed my investigative ardour, and made me aware of the rather grubby state of my hands.

Much later, during my student days, I once more ventured into McNaughtan’s, and found it the most inviting and fascinating haven. Every time I went in, Major or Mrs McNaughtan would show me one of their latest prizes; both were generous with the sort of information a less confident or enthusiastic bookseller might well regard as trade secrets. Major McNaughtan didn’t mind talking about his mistakes either: he once sold for a shilling the exceedingly scarce though physically unprepossessing first of Hadrian the Seventh (1904), by Frederick Rolfe, Baron Corvo. (The discovery of this work of tortured and bizarre genius had inspired A J A Symons to write The Quest for Corvo, ‘an experiment in biography’ published by Cassell in 1934, a brilliant, engrossing account of bibliographical and biographical detective-work which sparked off a small but fanatical Corvo cult). Major McNaughtan’s customer was kind enough to explain the significance of what he had just bought and, indeed, offered to pay more, an offer that was refused on the grounds that the original price must stand, and at any rate, a valuable piece of information had been received as part of the transaction.

Much later, during my student days, I once more ventured into McNaughtan’s, and found it the most inviting and fascinating haven. Every time I went in, Major or Mrs McNaughtan would show me one of their latest prizes; both were generous with the sort of information a less confident or enthusiastic bookseller might well regard as trade secrets. Major McNaughtan didn’t mind talking about his mistakes either: he once sold for a shilling the exceedingly scarce though physically unprepossessing first of Hadrian the Seventh (1904), by Frederick Rolfe, Baron Corvo. (The discovery of this work of tortured and bizarre genius had inspired A J A Symons to write The Quest for Corvo, ‘an experiment in biography’ published by Cassell in 1934, a brilliant, engrossing account of bibliographical and biographical detective-work which sparked off a small but fanatical Corvo cult). Major McNaughtan’s customer was kind enough to explain the significance of what he had just bought and, indeed, offered to pay more, an offer that was refused on the grounds that the original price must stand, and at any rate, a valuable piece of information had been received as part of the transaction.

To conclude our feature on McNaughtan’s Bookshop in Edinburgh, I asked Marjory McNaughtan to recall the early days of the shop, established in 1957.

‘Believe me, the first seven years were very hard. Everything we made was put back into the business to build up the stock, a general stock with a strong law section. When we first bought these premises in Haddington Place, we thought: as soon as we can possibly afford it we’ll move into town. But we became known and people started coming to us, until eventually we wouldn’t have moved for anything.’

It takes a cool head and a sharp eye to do well at auction:

‘The lane sales run by Lyon and Turnbull in Edinburgh were great fun. But after a while I realised that one of the other booksellers had noticed that we always did our homework, and that he was always trying to top my bids without really checking the books for himself…until the day I took him for a ride and bid him up on something that wasn’t worth two hoots.

‘I loved country house auctions; books tended to be sold by the shelf lot, and the only drawback to that was that there were one or two shady characters who would come on the last morning and shift books from shelf to shelf, trying to get all the best ones in the same lot.’

Mrs McNaughtan became well respected as an authority on early children’s books. I asked her how her special interest in juvenilia started.

‘It developed through my friendship with a customer, Professor Mason, who had a wonderful collection of children’s books. I first met him shortly after we started the shop. He heard that I had bought about forty ‘Books for the Bairns’ at what was then Dowells in George Street, and asked me if I would sell him some he lacked. I agreed to break the run for him. He was quite an expert both on German and English children’s book and we went on to become very friendly. He bequeathed his collection to the National Library of Scotland. I once got him two beautiful Horn Books. The earliest Horn Books are from the sixteenth century, and were used by children for learning their ABC. They’re in the shape of a baton, framed in wood, the older ones often leather-backed, with a piece of clear horn over the paper to protect them, and they display an ABC often in capitals and small letters, and frequently with a text underneath. By the way, I found Mrs E M Field’s The Child and his Book, published by Wells, Darton, Harvey and Co. in 1891, the most readable and instructive of all the books on children’s books, and it contains quite a lot of information on Horn Books.

‘I started collecting books about children, their games, toys and upbringing, and then incorporated the subject of early education, particularly the history of the development of free primary education, I also love children’s toys and games, and once had a lovely set of bricks which arranged properly showed maps of different parts of the world, all hand-coloured and with pictures of the inhabitants – boxed along with separate hand-coloured maps.

‘I remember in the early days buying a large library which had been left to a customer which contained Mrs Trimmer’s six volume Guardian of Education. I think I paid £5 for it because it really looked dull, but on closer inspection I found that at the end of each section – it was published first in monthly and then in three monthly parts – it contained reviews of all the contemporary children’s books. Very useful reference. Some of the comments were so funny. One story had a village girl marrying a squire’s son. Mrs Trimmer thought this was absolutely disgraceful! And then I established that The Guardian of Education was rare. At that point, I went back and paid the seller some more. Sheer conscience made me.

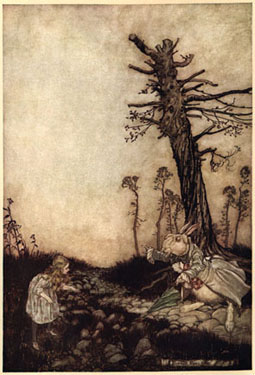

‘One of my great disappointments was when I went to Yorkshire to look at a big collection of books which had been left to a friend of my sister. I arrived to find that all the children’s books, including two Victorian musical picture books, had been given to the local Sunday School, where they were destroyed within a week. Incidentally, even at that time, twenty-five years ago, such musical picture books were worth sixty or seventy pounds apiece. I felt a similar sort of dismay when I walked into John Migdalski’s Broughton Books one Saturday afternoon, and there he was, a bucket of water beside him, washing the first edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. I immediately bought it from him. But the cover was ruined. If he’d only left it alone it could have been cleaned and repaired properly. It had to be rebound. The first issue of Alice was withdrawn, but this (1866) was the first fully published one, and there are very few of them.

‘One of my great disappointments was when I went to Yorkshire to look at a big collection of books which had been left to a friend of my sister. I arrived to find that all the children’s books, including two Victorian musical picture books, had been given to the local Sunday School, where they were destroyed within a week. Incidentally, even at that time, twenty-five years ago, such musical picture books were worth sixty or seventy pounds apiece. I felt a similar sort of dismay when I walked into John Migdalski’s Broughton Books one Saturday afternoon, and there he was, a bucket of water beside him, washing the first edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. I immediately bought it from him. But the cover was ruined. If he’d only left it alone it could have been cleaned and repaired properly. It had to be rebound. The first issue of Alice was withdrawn, but this (1866) was the first fully published one, and there are very few of them.

I particularly like the children’s books published by John Harris, successor to Newbery at the Corner of Old St Paul’s Churchyard. When I moved into a smaller house I sold most of my collection, but I still have one of my joys, The Cabinet of Lilliput, John Harris, 1802. It consists of twelve tiny volumes, each with two or three stories and engravings, housed in a miniature bookcase. When I first got it, there were only ten volumes. I was lucky enough to find the other two in somebody’s catalogue and bought them, but these haven’t been cropped to fit into the box.’

Mrs McNaughtan went on to show me Tales for Youth in thirty poems: to which are annexed, historical remarks and moral applications in prose by the author of Choice Emblems for the Improvement of Youth, Ornamented with Cuts, neatly engraved and designed on wood by Bewick, London, Newbery, The Corner of Old Saint Paul’s Church Yard, 1794.

‘They never could resist the moral applications. The engraver is John Bewick. He never was quite as good an engraver as his brother Thomas. But these are very nice cuts.’

‘They never could resist the moral applications. The engraver is John Bewick. He never was quite as good an engraver as his brother Thomas. But these are very nice cuts.’

Sydney Roscoe says in his bibliography John Newbery and his Successors 1740-1814, Five Owls Press 1973, ‘John Newbery’s achievement was not to invent these juvenile books, not even to start a fashion for them, but to produce them as to make a permanent and profitable market for them, to make them a class of books to be taken seriously as a recognised and important branch of the book-trade.’ Through the research and enthusiasm of people like Marjory McNaughtan there is now established what seems to be a permanent and profitable market for old children’s books, and while there’s a certain sadness at seeing books intended for younger readers locked well out of the way of their depredations, they are preserved to delight the child that is still there however old we grow.

© Jennie Renton 1986

Comments