Richard Woodhead

RLS and Bluidy Jack

I was seven years old when I first became aware of the name Robert Louis Stevenson. My friend’s mother – a bookish woman, clever at encouraging children to read – told me that my first two initials (R.L.) meant that I would like his books. ‘Start with Kidnapped,‘ she said,’not Treasure Island‘. By the time that I’d reached the House of Shaws in Chapter two, I was captivated. Since then, like so many others before and after me, I have devoured much of his glorious literature.

I was seven years old when I first became aware of the name Robert Louis Stevenson. My friend’s mother – a bookish woman, clever at encouraging children to read – told me that my first two initials (R.L.) meant that I would like his books. ‘Start with Kidnapped,‘ she said,’not Treasure Island‘. By the time that I’d reached the House of Shaws in Chapter two, I was captivated. Since then, like so many others before and after me, I have devoured much of his glorious literature.

My career was in hospital medicine; for a good number of years was a district general hospital physician in Bradford, Yorkshire (my home county). During these years my reading and interpretation of novels and biography was influenced, inevitably, by medical experience. Stevenson, affected by illness from an early age, was peculiarly fascinating: it was illness that dictated much of his extensive travelling, and it was travelling that restrained his illness, enabling him to become a prolific writer within a relatively short life span.

Since Stevenson’s death in 1894, numerous books and articles about him have contained the assumption – underlying or stated – that his illness was tuberculosis or, to use the nineteenth-century term, consumption. Admittedly, this has been questioned in some of the more recent biographies (such as Jenni Calder’s RLS: A Life Study and Frank McLynn’s Robert Louis Stevenson), but the general impression of Stevenson as a ‘consumptive’ persists.

This interpretation is based on his appearance (the scrawny body, the narrow chest, the brilliant eyes) and the opinion of his wife Fanny, who had a strong interest in medical matters, dating back to the death of her young son Hervey, from consumption, a few months before she met Stevenson.

I began to doubt that Stevenson had tuberculosis from the time that I read Graham Balfour’s 1901 biography The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson. In keeping with the conventions of his time, Balfour was discreet in writing of his cousin’s ill health (the word consumption being mentioned only once or twice) but he did describe how periods of illness were often triggered by colds. For this reason, I began to question a diagnosis of tuberculosis.

When I retired from my hospital post in 1997, I decided to look into Stevenson’s medical history in more depth. My interest in the subject was fuelled by reading those magnificent eight volumes, The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, edited by Booth and Mehew (Yale University Press, 1994 – 95); Stevenson’s correspondence is a fascinating adventure story in itself, rich in detail of everyday events. I focused on references to illness and followed up any source of information that was indicated. In this way I had the enjoyable experience of discovering such gems as W.G. Lockett’s Robert Louis Stevenson at Davos and Adelaide Boodle’s RLS and his Sine Qua Non.

When I retired from my hospital post in 1997, I decided to look into Stevenson’s medical history in more depth. My interest in the subject was fuelled by reading those magnificent eight volumes, The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, edited by Booth and Mehew (Yale University Press, 1994 – 95); Stevenson’s correspondence is a fascinating adventure story in itself, rich in detail of everyday events. I focused on references to illness and followed up any source of information that was indicated. In this way I had the enjoyable experience of discovering such gems as W.G. Lockett’s Robert Louis Stevenson at Davos and Adelaide Boodle’s RLS and his Sine Qua Non.

I realised that the question of Stevenson’s supposed tuberculosis couldn’t be proved or disproved, but that there was a wealth of information on which to base conjecture. If he didn’t have tuberculosis, then who created the myth that he did? – and why? Perhaps it was his doctors (he saw many doctors: eleven are named in his generous dedication of Underwoods, and he said ‘I forget as many as I remember’). Or perhaps it was his mother, or his wife, or even Stevenson himself (although he was no hypochondriac).

As so much of this was conjecture, I decided that fiction would be the best and most interesting way of releasing speculation. I began to write the story through the eyes of five physicians – real people – who treated Stevenson in various parts of the world. Their fictional first-person narratives allowed me to imagine how these doctors would have seen and influenced Stevenson, and how he would have influenced them. The fiction had to be based on a matrix of factual information in such a way that everything described was possible and believable.

The doctors proved to be interesting characters. In their younger days two (perhaps three) of them suffered from consumption and this coloured their views of the disease later on. They all seemed to mould their advice and treatment in accordance with the wishes and prejudices of Stevenson and his family in a way that contrasts with modern medical practice, which is driven by standardisation and protocol. Nineteenth-century physicians had little available in the way of diagnostic tests and effective therapy but they did have one great asset: time to listen to their patients.

There was only a limited amount of information available about ‘my’ doctors (Andrew Clark of London, Karl Ruedi of Davos, Thomas Bodley Scott of Bournemouth, E.L. Trudeau of Saranac Lake and Bernard Funk of Samoa), but I dug out what I could find.

Andrew Clark, although a famous man in his day (he became a baronet), never wrote much: his popularity depended on word-of-mouth recommendation. Fortunately for me, he left an archive to the library of the Royal College of Physicians of London. Reading Clark’s handwritten ‘Directions for managing an incipient feverish cold’ seemed to give more insight than the printed word into his character. In the same way, looking at Fanny Stevenson’s forcefully penned letters in the National Library of Scotland revealed something of her intense character.

In Bournemouth Library I found a memoir of Thomas Bodley Scott and some books relating to Bournemouth medical practice in the nineteenth century. For E.L. Trudeau’s history, I relied heavily on his autobiography, published in 1916. Trudeau was an eminent scientist who founded a sanatorium at Saranac Lake; the modern-day Trudeau Institute has a staff of over 100, working mainly in immunology. Information about Bernard Funk was more limited but the staff of the Apia Public Library kindly sent me a photograph and short biography from the 1907 edition of The Cyclopedia of Samoa.

In Bournemouth Library I found a memoir of Thomas Bodley Scott and some books relating to Bournemouth medical practice in the nineteenth century. For E.L. Trudeau’s history, I relied heavily on his autobiography, published in 1916. Trudeau was an eminent scientist who founded a sanatorium at Saranac Lake; the modern-day Trudeau Institute has a staff of over 100, working mainly in immunology. Information about Bernard Funk was more limited but the staff of the Apia Public Library kindly sent me a photograph and short biography from the 1907 edition of The Cyclopedia of Samoa.

I wrote the tale with the thread of another story running through it: the story of consumption in the second half of the nineteenth century, a time when over 50,000 people a year died of the disease in Britain alone. It was also a time of great scientific advance, most spectacularly in 1882 when Koch discovered the tubercle bacillus. Regardless of whether or not Stevenson actually had tuberculosis, the perception that he was suffering from the disease determined many important developments in his adult life. I found most of what I needed on the history of tuberculosis in that wonderful mine of information, the Wellcome Institute Library in London.

I made a deliberate decision not to follow in the footsteps of Stevenson (that would have produced an altogether different book) but I did make a few small-scale expeditions, to Edinburgh to seek out places associated with RLS and to Bournemouth, to stand on ‘Skerryvore’ territory and breathe in the wonderfully pure air breezing up Alum Chine. My trip to Cavendish Square, London, to look at Dr Clark’s home was less successful: not realising that the house had become a branch of Coutts Bank, I was startled by the emergence of the manager, worried that I was ‘sizing up’ his bank. (Fortunately my explanation satisfied him, leading to a courteous invitation inside to look through old photographs of the building.)

Writing and researching the story over nearly three years, I needed help to release my pen from the ‘control’ of more than thirty years’ experience of writing innumerable medical reports, but no fiction (at least, not consciously), and so I attended an Arvon Foundation course at Moniack Mhor, near Inverness, led by Hilary Mantel and Leslie Wilson, which I found invaluable.

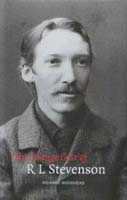

The resultant book, The Strange Case of R.L. Stevenson, offers more questions than answers. Was Stevenson master or victim of his illness? How did this affect his writing? Did Fanny Osbourne use the illness to further her own ambitions? How far did their own histories and prejudices influence the doctors? My hope is that readers will enjoy reaching their own conclusions.

The resultant book, The Strange Case of R.L. Stevenson, offers more questions than answers. Was Stevenson master or victim of his illness? How did this affect his writing? Did Fanny Osbourne use the illness to further her own ambitions? How far did their own histories and prejudices influence the doctors? My hope is that readers will enjoy reaching their own conclusions.

The Strange Case of Robert Louis Stevenson by Richard Woodhead is published in hardback at £16.99 by Luath Press. Contact: Luath Press, 543/2 Castlehill, Edinburgh, Scotland. Tel: 0131 225 4326 www.luath.co.uk

© Richard Woodhead 2005

Comments