Daiches bibliography

One of the Exceptions

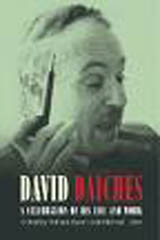

Not every academic (alas) deserves to be remembered after death, and even fewer academics deserve to be remembered by those outside the academic community. David Daiches, who died at age 92 in 2005, was one of these few. William Baker and Michael Lister have given us this collection of memories and assessments of Daiches, which will certainly stand as a major monument to Daiches’ achievement in many different fields, celebrating his invaluable contributions to the study of Scottish literature and culture, to English and American literary criticism and to the development of English literature studies. Then there is the celebration of what for many was his most significant work, of articulating the duality at the heart of our cultural identity, which has given us new understanding of Scottish themes and shed new light on the wide range of writers of all ages and locations whom Daiches wrote about during his long and productive career. Daiches’ scholarly and critical writing serves as a model of balanced, humane engagement with literature; his autobiographies (which have not dated) have long been accepted as important accounts of Scottish and Jewish culture and his poems will survive as thoughtful and compassionate insights delivered in witty and elegant language. Daiches also embraced the role of the academic in the public media, both on radio (143 radio appearances, stretching from 1951 to 1989, are listed in the bibliography) and on television (especially in the 1950s on The Brains Trust and Who Said That?).

Not every academic (alas) deserves to be remembered after death, and even fewer academics deserve to be remembered by those outside the academic community. David Daiches, who died at age 92 in 2005, was one of these few. William Baker and Michael Lister have given us this collection of memories and assessments of Daiches, which will certainly stand as a major monument to Daiches’ achievement in many different fields, celebrating his invaluable contributions to the study of Scottish literature and culture, to English and American literary criticism and to the development of English literature studies. Then there is the celebration of what for many was his most significant work, of articulating the duality at the heart of our cultural identity, which has given us new understanding of Scottish themes and shed new light on the wide range of writers of all ages and locations whom Daiches wrote about during his long and productive career. Daiches’ scholarly and critical writing serves as a model of balanced, humane engagement with literature; his autobiographies (which have not dated) have long been accepted as important accounts of Scottish and Jewish culture and his poems will survive as thoughtful and compassionate insights delivered in witty and elegant language. Daiches also embraced the role of the academic in the public media, both on radio (143 radio appearances, stretching from 1951 to 1989, are listed in the bibliography) and on television (especially in the 1950s on The Brains Trust and Who Said That?).

The breadth of Daiches’ achievement is indicated merely by the variety of topics discussed in the essays Baker and Lister collect: Jewish culture in pre-1939 Edinburgh; Hebrew literature, including the Bible; Scottish education between the wars; the early years of New Criticism; the renaissance in twentieth-century Scottish literary criticism. Essays highlight the significance of Daiches’ contribution to critical appreciation of writers including Milton, Prior, Austen and Conrad. He is shown against a variety of different academic backgrounds: first the University of Edinburgh and Balliol College, Oxford, where he studied, and then through his career at the University of Chicago, Cornell University, Cambridge University, the University of Sussex and back to the University of Edinburgh as Director of the Institute for Advanced Studies.

The breadth of Daiches’ achievement is indicated merely by the variety of topics discussed in the essays Baker and Lister collect: Jewish culture in pre-1939 Edinburgh; Hebrew literature, including the Bible; Scottish education between the wars; the early years of New Criticism; the renaissance in twentieth-century Scottish literary criticism. Essays highlight the significance of Daiches’ contribution to critical appreciation of writers including Milton, Prior, Austen and Conrad. He is shown against a variety of different academic backgrounds: first the University of Edinburgh and Balliol College, Oxford, where he studied, and then through his career at the University of Chicago, Cornell University, Cambridge University, the University of Sussex and back to the University of Edinburgh as Director of the Institute for Advanced Studies.

In only the first three pages of Martin Bidney’s opening article, there are references to Stevenson, Matthew Arnold, the psychologist Frank Sulloway, Hume, Kant, the Talmud, the modern Hebrew poet Saul Tchernikhovsky, John Stuart Mill and Freud, as well as several members of Daiches’ family, an account of various approaches to Jewish practices and identity, an account of morning prayers in the Daiches household and the education of David’s father, Rabbi Salis Daiches.

The book consists of twenty-four essays and poems by friends, colleagues and family members, as well as short introductions by each of the editors and an extensive primary and secondary bibliography stretching over eighty-seven pages, which the editors acknowledge is still incomplete. The contributions are short and for the most part free from obstructive jargon, making this an easy, friendly book to read. If anything, some of the pieces tend to become a little too friendly and anecdotal. At their best, though, they achieve what we would desire (and what Daiches himself desired from literature): an engagement with a fascinating subject located in an intricate context, interesting in himself and also for the insight he gives into our own lives.

The articles appear alphabetically by author, from a comparison of Daiches’ early poetry with Muriel Spark’s schoolgirl poems written at the same time also in Edinburgh, to a review of his critical writing on Milton, followed by three essays examining his achievements in promoting Scottish literary studies and an assessment of the slogan ‘One City’ in the light of the dualities found in Stevenson’s and Daiches’ accounts of Edinburgh. This arrangement makes for invigorating reading – like moving among a mixed group of interesting people gathered to celebrate this man they hold in common. ‘Oh, you here too? Join the party!’

(That reminds me of one omission. Although Daiches’ love for whisky is acknowledged in many places, I would have liked to learn more about what effect his books on whisky may have had on other books of this genre or on popular appreciation or understanding of whisky. Or are we to regard these books as just trifles in the larger, more serious oeuvre?)

To take us a little further into the different aspects of David Daiches this book offers us, let me de-alphabetise the contributions and discuss them under different categories.

David Daiches the person

Many of the contributors offer biographical details (which perhaps inevitably tend to repeat themselves through the book). Many of the details come from Daiches’ autobiographies, many from personal anecdotes. Janet Burroway, for instance, shows the private side of Daiches’ relationships with his students and younger colleagues. Her article is particularly welcome for the only sustained description in the book of Daiches the man: ‘David was in these years [the 1960s, at Sussex] large-hearted, witty, erudite, and vain. He expected to be the centre of attention, but he had no tinge of the little-man’s Napoleonic meanness. His natural state of being was delight: delight in language, family, history, babies, rhyme schemes, verbal trickery, anybody’s happiness, unblended whisky, high discourse, repartee, and praise.’

Many of the contributors offer biographical details (which perhaps inevitably tend to repeat themselves through the book). Many of the details come from Daiches’ autobiographies, many from personal anecdotes. Janet Burroway, for instance, shows the private side of Daiches’ relationships with his students and younger colleagues. Her article is particularly welcome for the only sustained description in the book of Daiches the man: ‘David was in these years [the 1960s, at Sussex] large-hearted, witty, erudite, and vain. He expected to be the centre of attention, but he had no tinge of the little-man’s Napoleonic meanness. His natural state of being was delight: delight in language, family, history, babies, rhyme schemes, verbal trickery, anybody’s happiness, unblended whisky, high discourse, repartee, and praise.’

Alastair Fowler shares time spent with Daiches in his later years, most memorably a long discussion they had walking back through George Square after a lecture. The topics covered were typically wide-ranging: the averted sacrifice of Isaac in Genesis, Kierkegaard, and the mediaeval poems Piers Plowman and The Court of Sapience. As Fowler’s Christian and Daiches’ Jewish viewpoints came into conflict, Daiches abandoned what Fowler calls ‘the tact and caution requisite in treating charged topics at the edge of cultural divides’ and threw himself into ‘freely exchanged disagreements’. An angry, bitter quarrel? Not at all: this was ‘disaccord expressed in an amicable tone’ – a serious argument but always with that respect and humanity shaping the engagement.

But it is the two poetic contributions that come closest to the man (who would have been pleased to see this). Jenni Calder’s poem ‘Longer Days’ describes a visit to her father late in his life on ‘a calm, grey autumn evening’. Here is the closing section: We sit at the window and talk/ not of the troubled world or promised lands/ but of the magnolia across the street,/ a candelabra of creamy flames.

We talk not of God or war,/ love or hate or other extremes,/ not of absence or loss or grief,/ but of longer days and leaves and light,/ the haunted tenacity of life.

Alan Riach produces a portrait of Daiches through the ‘co-ordinate points’ of nine short poems, creating a unity larger than its parts. Here is the sixth poem, ‘In the Caledonian Hotel’: ‘If you come upstairs, your table will be ready.’/ The waitress had gone before she could have seen/ your face already smiling at/ the multiple strangeness of that: ‘If we don’t go upstairs,/ will it not be ready? And how could she know/ that it will be, not/ that it already is?’ The momentary/ pleasure of it privilege allows, that vulnerable,/ almost-nonsense thing, savoured, saved.

David Daiches as critic

We will want to divide the essays on Daiches’ literary criticism into a few subgroups.

The critic as a mediator or bridge

Two fine essays focus particularly on Daiches’ ability to span attitudes and approaches. Martin Bidney discusses the way Daiches’ balanced critical writing combines, among other things, ‘a formalist attentiveness to language’ with ‘the cultural historian’s feeling for the dilemmas of people living in a society and within a tradition’. He focuses on the important later book God and the Poets (1984, based on his Gifford Lectures), ‘colorfully Hebraeo-Caledonian’ book, as Bidney puts it, but one that speaks to other interests besides the central Jewish and Scottish subjects: Wallace Stevens, Milton, Dante, Horace. The article concludes with a serene and touching eulogy: ‘Daiches, the Scots Jew, is a classical humanist, at home in his plural worlds, and with his plural identity.’

Jenni Calder’s essay connects vivid family vignettes into a coherent and insightful intellectual context. She stresses the difficulties and complexities of living in ‘two worlds’ and dealing with ‘the degrees of assimilation, synthesis and alienation. Assimilation is not a steady process, working its way by stages down through the generations. It is diverted and disrupted in all kinds of ways, as well as being resisted and challenged.’ It is no good studying the context of a life or a text without remembering that all context is dynamic and complex. We need bridges to make sense of this complexity, and Daiches was proud to say, ‘Bridge-building is my vocation.’ No wonder literature was so important to him, as (perhaps only temporarily) a way out of our confusion. He stressed ‘the role of literature as an illumination of life, a bridge between different kinds of experience, different environments, physical, cultural emotional and spiritual’. Here we see the most significant bridge Daiches constructed again and again, between the literary text and the human experience of those reading the text.

Critic of Scottish literature

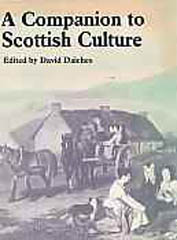

Douglas Gifford acclaims Daiches categorically as ‘the father of modern – and international – Scottish literary criticism, whose revaluations have changed our maps forever’. He calls attention to the three central revaluations, all within a few years of each other, of Stevenson, Burns and Scott. Also central is Daiches’ articulation of the thread of dualism in Scottish identity and literary themes. Gifford also draws our attention to the important work Daiches performed beyond his writing, as director, founder and supporter of many literary and cultural bodies and his work promoting many anthologies and new editions of important writers.

Like Gifford, Andrew Hook has no doubt about the praise owing to Daiches as ‘the finest and most creative scholar and critic of Scottish literature in the twentieth century’. He especially praises Daiches’ work on ‘the cultural history of eighteenth-century Scotland, the poetry of Robert Burns, and the fiction of Sir Walter Scott’.

R.D.S. Jack takes a different angle, digging up the literary texts Daiches would have studied when reading English at Edinburgh University in the early Thirties (none of them Scottish), and then contrasting this absence to the place in the curriculum of Scottish writers today, thanks to a great extent to the early and important voice of Daiches.

These articles took me back to when I myself studied under Ron Jack, Ian Campbell and John MacQueen in 1969 – the first year Edinburgh offered a Scottish literature course. What I accepted then as a long-standing, established approach to Scottish literature, so confidently and coherently presented to us, I discovered only later was radically new and, as these three essays clearly demonstrate, derived largely from the work of David Daiches.

Critic of English literature

Ira Nadel assesses Daiches’ work on Modern writers, and the way Daiches’ criticism balanced different critical traditions (the Edinburgh tradition he inherited from Saintsbury and Grierson, for instance, alongside the New Criticism he encountered in Chicago), and was shaped by Daiches’ insistence that the aim of criticism was to ‘assist the experience of literature’. Nadel catalogues much of Daiches’ writing on Modern literature (including high praise for the concision, clarity and depth of the introductions to the twentieth-century writers in the Norton Anthology of English Literature) and the influence of this writing on other critics.

I want to single out Roger Savage for his exceptional essay. Savage limits his subject to only a minor poem by Matthew Prior, ‘Written in the Beginning of Mézeray’s History of France’ but his affable and intelligent inquiry into Daiches’ connection to the poem takes us far beyond the poem itself. Savage performs the kind of critical balance sometimes praised by others as a feature of Daiches’ criticism, as he uses the poem to study Daiches’ intellectual and academic roots (the context) as well as Daiches’ comments on the language itself (the text). Then back to context again as he connects the poem to Daiches’ work on Milton and the Bible, and to his own poetry. Savage offers us, the readers, a place at the end of a long and distinguished chain, linking Prior to Scott, who quoted the poem to Lockhart in the last year of his life, and to Saintsbury and Grierson, both of whom commented on the poem. And as Daiches passed the poem on to Savage, so Savage passes it on to us. This is criticism as a living tradition.

The final essay of the collection, by Melora Vandersluis, speaks about Jane Austen (Daiches’ favourite author in his last years, as Fowler tells us). Although Daiches claimed Austen was ‘firmly rooted in one world’, the world of women’s domestic concerns, Vandersluis shows that the same kind of duality found in Two Worlds and in so many other places in Daiches’ writing can also be found in Austen’s ‘navigating between the world of women and, at least professionally, the world of men’. Gender politics enables her to adjust Daiches’ view at the same time as Daiches’ theme of duality gives shape to the gender politics. This is the only essay in the book that engages in a critical debate with Daiches, and it fits well.

Critic of Jewish literature

There is some, but not enough, attention to Daiches’ work on Jewish literature. Martin Bidney devotes some attention to Daiches’ work on the Bible and David Daiches Raphael offers us a run-through of some of the work on Jewish subjects, but it would have been good to have a more sustained discussion.

David Daiches in the university context

Asa Briggs, Angus Ross and Ian Simpson Ross, among others, document Daiches’ contribution to academia, especially to the founding of the University of Sussex. I am unable to judge how valuable these facts and anecdotes are for the historian of British universities, or to what extent they are of interest to people of later generations. It is right, however, that they should be an important feature of this book.

David Daiches as public figure

Paul Henderson Scott reminds us of the many roles Daiches undertook to promote Scottish culture through the Saltire Society, the Advisory Council for the Arts in Scotland and other bodies.

Paul Henderson Scott reminds us of the many roles Daiches undertook to promote Scottish culture through the Saltire Society, the Advisory Council for the Arts in Scotland and other bodies.

The Sussex Academic Press web site tells us that this book will speak about ‘the academic as populariser’ but we don’t see much of this. The long list in the bibliography of addresses and radio and television appearances is impressive. But those of us who missed these appearances or who cannot remember them would have been grateful for some intelligent assessment of how well Daiches adjusted to this different medium and of how he helped inform popular attitudes towards fine literature.

Other contributions

I was disappointed in a handful of contributions to the book that mention Daiches once at the start and then proceed with their own subject – on Milton and Prior, Carlyle, Hebrew poetry. Interesting though they may be, these studies added no further insight into or celebration of Daiches’ life or work.

I hope that the Sussex Academic Press will issue a new edition soon, correcting the many errors that have been allowed to pass into print here. But this is not the note to end with. Instead, let us remember what Daiches once wrote to Janet Burroway: ‘Most academics are fools (this is a secret, and mentioned in confidence) [

...]. I say most, not all; academic life is lit up by the exceptions.’ As we read this book we learn, if we did not know already, that David Daiches was one of the exceptions, and we celebrate him.

David Daiches: A Celebration of His Life and Work edited by William Baker and Michael Lister is published by Sussex Academic Press, 2008

© Robert Louis Abrahamson 2008

Comments