Ballantyne

Words for the Young

In an Introduction to an edition of Ballantyne’s Coral Island in 1913, J.M. Barrie began ‘To be born is to be wrecked on an island’.

Scottish writers have made a notable contribution to children’s fiction. A tradition of literacy, and access to the huge English reading market have helped, the result being books memorable in most instances for everything except their Scottishness, though, as with our quote from Barrie, the Scottishness will always find a way out.

Scottish writers have made a notable contribution to children’s fiction. A tradition of literacy, and access to the huge English reading market have helped, the result being books memorable in most instances for everything except their Scottishness, though, as with our quote from Barrie, the Scottishness will always find a way out.

The first notable work for children was Walter Scott’s Tales of a Grandfather (1st series 3 vols 1827-28). This retelling of stories from Scottish history broke into a market monopolised by works designed to ‘teach lessons and convey information to assist in forming and strengthening the character’. Sandwiched between ‘Lines on the Death of an Infant’ and yet another Intercession of Christ the Redeemer one might learn that ostriches habitually ate iron nails. Facts were heavily outweighed by ponderous moralising, fantasy turned out in the straitjacket of morbid religiosity. No collection of early Scottish children’s books should be without The Nursery Offering or Children’s Gift, or its stable-mate The Excitement, annual productions from Edinburgh publisher Waugh & Innes, contemporaneous with Scott’s Tales of a Grandfather. These strong poisons were attractively packaged in Arabesque bindings, illustrated with hand coloured plates and wood engravings.

An important departure from this school was Catherine Sinclair’s Holiday House published in 1839, in which juvenile mischief is treated in a light-hearted manner. Miss Sinclair wrote one other children’s book, Charlie Seymour, 1832, although her Letters, 1861-64 should also be included, being amusing ‘hieroglyphics’ small pictorial representations replacing many words.

R M Ballantyne is one of the most important writers for children from the middle of the nineteenthth century with such books for boys as The Young Fur Traders (originally titled Snowflakes and Sunbeams (1856), Coral Island (1858), Martin Rattler (1859) and The Gorilla Hunters (1861), through some hundred books in all until his death in 1894. His early works were a major influence on the young Robert Louis Stevenson, and are read avidly to this day. The settings (rarely Scottish) represent the almost limitless horizon for middle-class Victorian boys; the empire their oyster. Ballantyne also wrote some grimly humorous works for younger children in the 1850s, such as The Robber Kitten (1858) under the pseudonym ‘Comus’. As with his books for boys they contain his own illustrations (except for The Butterfly Ball, 1857).

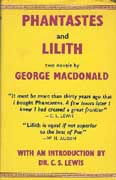

A contemporary of Ballantyne’s writing very different works for children was George Macdonald, whose allegorical and dream world novels and stories make him one of the fathers of modern fantasy writing. His first work for children, a collection of short stories called Dealing with the Fairies was published by Strahan in 1867. It was illustrated by Arthur Hughes, Macdonald’s most trusted illustrator. For two years Macdonald edited Good Words for the Young (1870-72) in which were serialised several of his works; Ranald Bannerman’s Boyhood (1871) Gutta Percha Willie (1872) and before his editorship, possibly his best known work, At The Back of the North Wind (1869-70).  All Macdonald’s works are difficult to find in first editions and are extremely expensive, especially At The Back of the North Wind (1871), The Princess and the Goblin (1872), The Princess and Curdie (1883) and Phantastes (1858), his first prose work, which though not expressly written for children has been adopted by them to some degree. Although ‘firsts’ might prove prohibitive to the average collector there are many early editions to be found for a few pounds each.

All Macdonald’s works are difficult to find in first editions and are extremely expensive, especially At The Back of the North Wind (1871), The Princess and the Goblin (1872), The Princess and Curdie (1883) and Phantastes (1858), his first prose work, which though not expressly written for children has been adopted by them to some degree. Although ‘firsts’ might prove prohibitive to the average collector there are many early editions to be found for a few pounds each.

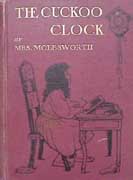

A writer not always thought of as Scottish was Mrs Molesworth, author of, amongst over a hundred others, The Cuckoo Clock (1877) and Carrots (1876). Both of these were written under the pseudonym Ennis Graham, and both were illustrated by Walter Crane. Born in Rotterdam of Scottish parents, she spent childhood holidays in Scotland and wrote some of her books in Edinburgh where she lived for several years.

A writer not always thought of as Scottish was Mrs Molesworth, author of, amongst over a hundred others, The Cuckoo Clock (1877) and Carrots (1876). Both of these were written under the pseudonym Ennis Graham, and both were illustrated by Walter Crane. Born in Rotterdam of Scottish parents, she spent childhood holidays in Scotland and wrote some of her books in Edinburgh where she lived for several years.

Perhaps the best loved of Scotland’s writers for children is Robert Louis Stevenson. His first book for children was Treasure Island, serialised in Young Folks between October 1881 and January 1882, under the pseudonym Captain George North, only established its success when published in book form in 1883. His Child’s Garden of Verses, a small powder blue volume, was published in 1885 although thirty-nine of the sixty-four poems were privately printed in 1883 under the title Penny Whistles. There were subsequently many illustrated editions of the Child’s Garden, probably the most enduring being that illustrated by Charles Robinson (1895). All of Stevenson’s other juvenile works are relatively easy to find in first edition: Kidnapped (1886) and its sequel Catriona (1893), The Black Arrow (1888) and The Master of Ballantrae (1889).

At the end of the nineteenth century on the tide of folklore revival,  Andrew Lang edited his celebrated series of colour Fairy Books. He wrote other works for children but it is the Fairy Books which collectors hunt. The Blue Fairy Book was the first (1889) followed by the Red (1890), Green (1892), Yellow (1894), Pink (1897), Grey (1900), Violet (1901), Crimson (1903), Brown (1904), Orange (1906) and finally Lilac (1910). Reprints of many of these can be found quite easily and cheaply in second-hand bookshops, first editions less easily, and really good to fine copies are very expensive indeed. Some colours are almost impossible to find in their original finery, particularly the paler colours, where colour and gilt work have been ravaged by sunlight and dust. Only copies preserved (as some were) in brown paper are likely to have survived in all their glory, and such a copy might cost ten times as much as a marked, dull one. All the Fairy Books are illustrated in Pre-Raphaelite style by H J Ford (the Blue Fairy Book in conjunction with G P Jacomb Hood, the Red with Lancelot Speed).

Andrew Lang edited his celebrated series of colour Fairy Books. He wrote other works for children but it is the Fairy Books which collectors hunt. The Blue Fairy Book was the first (1889) followed by the Red (1890), Green (1892), Yellow (1894), Pink (1897), Grey (1900), Violet (1901), Crimson (1903), Brown (1904), Orange (1906) and finally Lilac (1910). Reprints of many of these can be found quite easily and cheaply in second-hand bookshops, first editions less easily, and really good to fine copies are very expensive indeed. Some colours are almost impossible to find in their original finery, particularly the paler colours, where colour and gilt work have been ravaged by sunlight and dust. Only copies preserved (as some were) in brown paper are likely to have survived in all their glory, and such a copy might cost ten times as much as a marked, dull one. All the Fairy Books are illustrated in Pre-Raphaelite style by H J Ford (the Blue Fairy Book in conjunction with G P Jacomb Hood, the Red with Lancelot Speed).

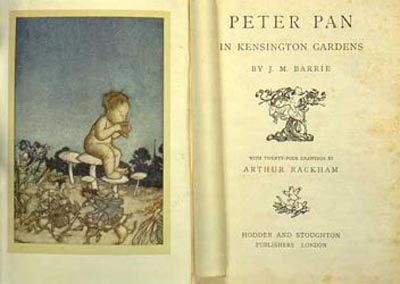

Finally we come to the two ‘Home Counties’ Scots – J M Barrie and Kenneth Grahame. Barrie’s famous work Peter Pan was produced as a play in 1904 although its earliest appearance occurs in The Little  White Bird (1902). The most desirable edition of the book is probably Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906), illustrated by Arthur Rackham and produced as a sumptuous Christmas gift book, though whether any but the most goody-goody child wearing cotton gloves ever handled it is debatable. Another version entitled Peter and Wendy, illustrated by F D Bedford was published in 1911.

White Bird (1902). The most desirable edition of the book is probably Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906), illustrated by Arthur Rackham and produced as a sumptuous Christmas gift book, though whether any but the most goody-goody child wearing cotton gloves ever handled it is debatable. Another version entitled Peter and Wendy, illustrated by F D Bedford was published in 1911.

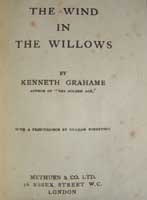

Kenneth Grahame’s classic, The Wind in the Willows (1908) sported only a frontispiece by Graham Robertson. Arthur Rackham was asked to illustrate the first edition but was unable to accept the commission (this he remedied late in life and ‘his’ version was published by the Limited Edition Club of New York in 1940; a British published edition, 1951). The most popular of the many illustrated editions has proved to be that by E H Shepherd (38th edition, 1931).

Kenneth Grahame’s classic, The Wind in the Willows (1908) sported only a frontispiece by Graham Robertson. Arthur Rackham was asked to illustrate the first edition but was unable to accept the commission (this he remedied late in life and ‘his’ version was published by the Limited Edition Club of New York in 1940; a British published edition, 1951). The most popular of the many illustrated editions has proved to be that by E H Shepherd (38th edition, 1931).

Although these works mentioned might be considered the High Road of Scottish Children’s Books, there are many others. Early tracts, chapbooks and regional printings may be found. Individual taste might include Mrs George Cupples, Ian Maclaren, S R Crockett, Eric Linklater, Compton Mackenzie, John Buchan, Dorita F Bruce, or any of the different runners from the rich D C Thomson stable.

Copyright Bookworm.

Comments