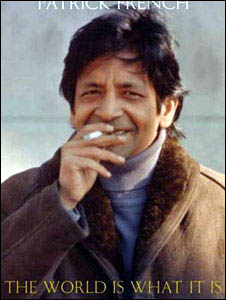

The World Is What It It

Naipaul Mapped

Life lived as polemic. That’s one way to see V.S. Naipaul, through the lens of Patrick French’s brilliant account of a writer whose identity has been forged in the struggle against stereotyping and yet who has sometimes seemed to provoke it. French gets behind Naipaul’s public persona – ‘the mask that eats into the face’ – allowing ambiguities the power to illuminate, or even to perplex. In laying down his credo as a biographer, he refutes any notion that a biography can be the ‘key’ to its subject: The World Is What It Is may be seen as a map of Naipaul’s doings and identity, but map and territory are not one and the same, as has been famously said.

French’s reluctance to ‘possess’ his subject represents a real strength. He is an excellent stylist and a great admirer of Naipaul’s work. On being approached to write this authorised biography, he was cautious about taking on the project and armoured himself to resist egotistical demands from his notoriously vain subject. There were none. Anticipating the danger of being seen as a ‘yes man’, he insisted on an entirely free hand to report his researches. There was no demur. He requested access to the author’s complete archive at the university of Tulsa, which includes material that Naipaul himself had never examined. Permission was granted. There ensued a series of face-to-face, sometimes highly emotional interviews, which French describes as the most extraordinary of his professional career.

Naipaul stuck to his stated conviction that writers’ lives ‘are a legitimate subject of enquiry; and the truth should not be skimped’. The interplay of his recollections with divergent accounts of the same events, by others or by his earlier self, is deftly managed and much fascination lies in discrepancies of narrative, whether subtle or irreconcilable. For example, when he was working for the BBC, Naipaul had a bitter falling out with a producer called Billy Pilgrim (this was long before Vonnegut penned Slaughterhouse-Five). The issue was a finger raised in a gesture which might have been contemptuous or a simple indication that silence was required in the recording studio. Naipaul, who measured every ounce of contempt he dealt or received, insisted that he had been insulted. Having reported his furious rant, French wryly observes: ‘So it goes.’

‘His public position as a novelist and chronicler was inflexible at a time of intellectual relativism: he stood for high civilization, individual rights and the rule of law.’ All the more shocking, then, the gulf French reveals between Naipaul’s public accomplishments and private shortcomings, particularly in his behaviour towards many of the women closest to him. He met his wife Pat at Oxford, where both had gained entrance through scholarships. Perhaps their attraction lay partly in the fact that they were outsiders, she with her English working-class background and efforts to iron out her vowels with elocution, and he with the crowded home and complicated politics of extended family back in Port of Spain, a hugger-mugger way of life that he describes as ‘peasant’, but which gave him the seed-corn for his first novels.

Naipaul attributes the nervous breakdown he suffered at university to the racism he encountered. His sister Mira, with whom he conducted a lively and fond correspondence, didn’t ‘get’ what he meant until she came to Britain herself: ‘It took me six months in Edinburgh to understand class and people and behaviour. You had read Jane Austen

… but you had not lived in the country.’

On graduating, he struggled to find work. Asked why he didn’t go back to Trinidad and ‘serve his country’ he would respond, ‘What country? A plantation?’ Like his father – their relationship and its influence on his work is beautifully delineated – Naipaul’s self-belief was precarious. Pat’s devotion steadied him; she was prepared to ‘sacrifice life to self sacrifice’. Although he now asserts that he never wanted children, this is not borne out by letters quoted here and his very denial indicates quite how painful childlessness was to him. In a letter written in her early twenties, Pat imagines them at thirty: he will have his first literary success and they will have two children, a little boy named Humphrey and a little girl wearing plaits. He is frank about how shy they were when it came to sex. The unspoken tensions about fertility must surely have exacerbated their awkwardness.

In a bout of terrible honesty, Naipaul gave an interview reporting that he had turned to prostitutes for sexual satisfaction from early on in their marriage. He suggests to French that this may have hastened Pat’s death from cancer, ending a remission. In the final pages of The World Is What It Is we find him sobbing at Pat’s grave – in the company of her swiftly installed successor. French regards Patricia Naipaul’s diaries as ‘an essential, unparalleled record’, putting her ‘on a par with the other great, tragic literary spouses such as Sonia Tolstoy, Jane Carlyle and Leonard Woolf.’

Following Pat’s death, Naipaul terminated a 20-year relationship with his Argentinian-Scottish mistress. In an early letter to him, Margaret Gooding quotes Robert Graves: ‘love is the disease worth having’. With her, Naipaul discovered his ‘carnality’. It was no sweet and gentle thing. He also discovered that he was not firing blanks. Shocked and elated at the news of her first pregnancy, he wondered aloud to acquaintances at a dinner party whether he might raise the child with his wife. A few days later, he was informed that the ‘problem’ had been seen to.

All this messiness raises the difficult question, should the genius or integrity of the artist be expected to extend to personal life? Humphrey Bogart was an informer to Senator McCarthy’s notorious Un-American Activities committee. Do we therefore turn a deaf ear when he asks Sam to play it again? (Or listen up, according to attitude.) Jean Rhys could be a crude racist when drunk. Does that subtract from the extraordinary sensitivity of her fiction? French insists that Naipaul’s ‘moral axis was

… internal, it was himself.’

Descended from Indian indentured labourers who settled in Trinidad in the late nineteenth century, Naipaul first visited the land of his forbears in 1962, when he was 29. He and Pat had intended to drive all the way in a converted Volkswagen van but failed to get comprehensive insurance and travelled instead, ‘securely if prosaically’, by sea. His impressions of India, including a six-month stay in Kashmir, were published as An Area Of Darkness. Naipaul did not stint himself when it came to expressing his disgust at the sight of people defecating in public. He succeeded in stirring up outrage. No stranger to controversy, he responded with disdain: ‘I begin to feel that I coined the word and devised the act.’

French gives an engrossing account of Naipaul’s childhood and shows how life events influenced his direction as a writer. Among the array of opinions which balance his own perspective on ‘the man without loyalties’ is Linton Kwesi Johnson’s view of Naipaul, as ‘a living example of how art transcends the artist ‘cos he talks a load of shit but still writes excellent books.’

The World Is What It Is: The Authorized Biography of V.S. Naipaul by Patrick French. Picador. Hardback. £20.

© Jennie Renton

Comments