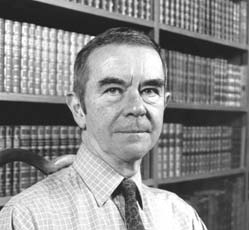

John Sibbald

Booked for Life

By any standards, John Sibbald’s career in the world of books has been extraordinary. At the age of thirteen, it was his habit to devote every Saturday morning to going round the Edinburgh secondhand bookshops, ‘trying to make booksellers part with things at improbable prices.’ He still has in his possession the booklet he typed up, listing the books he acquired 1958-59, and noting the prices paid. ‘I suppose that was a way of trying to encourage my not-so-doting parents to fork out more pocket money,’ he comments dryly. Every inch a bookman, his latest role is book expert for auctioneers Lyon and Turnbull.

At sixteen, John Sibbald decided he had a vocation for the church and made what (from the book-trade perspective) might be described as a sideways move by taking himself off to an Anglican religious house to train as a priest. As part of that training, he spent a year working in an Electrical Works in Manchester.

At sixteen, John Sibbald decided he had a vocation for the church and made what (from the book-trade perspective) might be described as a sideways move by taking himself off to an Anglican religious house to train as a priest. As part of that training, he spent a year working in an Electrical Works in Manchester.

‘It was thought to be useful for people who had led a privileged, middle-class life to see how the industrial masses heaved and sweated. Right in the middle of Trafford Park was a grid of houses where the workers lived, surrounded by miles of factories, furnaces and railway lines. I had digs there in a two-up two-down with a lean-to kitchen. I remember one rainy day straight out of a Lowry painting:thousands of people dispersing to their various factories, and me the only figure in the crowd holding an umbrella. It appeared to be the only umbrella in Salford.’

Left:The Book Review for 1958-59

Having tested his vocation and found it wanting, he went to live in France for three years. By the time he came back to Britain, he had conceived the ambition to enter the Fine Art world. In order to get a foothold in London, he applied for a job with W.H. Smith’s and was offered a sales position in their Cambridge branch. But it was when he moved on to a post as a librarian at one of the university colleges that he began to get to know people in the rare books trade. In 1969 he was head-hunted by Deighton Bell & Co. Founded in 1700, Deighton Bell was the second-oldest book business in the world. Its narrow, early eighteenth-century premises stood on the corner of Green Street and Trinity Street.

He had been taken on to catalogue the residue of the library of Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, recently acquired through Sotheby’s by Dawsons of Pall Mall (owners of Deighton Bell); the library had been put up for sale by the legendary London booksellers, Lionel and Philip Robinson.

‘Fletcher travelled extensively and acquired many of his books abroad and in 1682, he, or his agent, attended the sale of the great library of Nicolaus and Daniel Heinsius. I myself have Fletcher’s copy of the sale catalogue (known as the Heinsiana), which contained nearly 13,000 entries, with the prices marked in ink. His library remained virtually intact until the 1940s, when the Robinson brothers were allowed to purchase certain items. Their 1948 catalogue offered such plums as Fletcher’s first editions of Descartes’ Discours and Locke’s Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina. In 1966 the whole library went to Sotheby’s. The Book Department was then under great pressure, handling the Clements Library, Part Two of Major Abbey’s great travel collection and Part Two of the Bibliotheca Phillippica, and the Fletcher books perhaps did not receive the attention they deserved. They were eventually acquired by Dawsons of Pall Mall for a mere £2000.’ Ninety-four tea chests containing over 4000 volumes were despatched to Cambridge.

‘Fletcher travelled extensively and acquired many of his books abroad and in 1682, he, or his agent, attended the sale of the great library of Nicolaus and Daniel Heinsius. I myself have Fletcher’s copy of the sale catalogue (known as the Heinsiana), which contained nearly 13,000 entries, with the prices marked in ink. His library remained virtually intact until the 1940s, when the Robinson brothers were allowed to purchase certain items. Their 1948 catalogue offered such plums as Fletcher’s first editions of Descartes’ Discours and Locke’s Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina. In 1966 the whole library went to Sotheby’s. The Book Department was then under great pressure, handling the Clements Library, Part Two of Major Abbey’s great travel collection and Part Two of the Bibliotheca Phillippica, and the Fletcher books perhaps did not receive the attention they deserved. They were eventually acquired by Dawsons of Pall Mall for a mere £2000.’ Ninety-four tea chests containing over 4000 volumes were despatched to Cambridge.

From his office on the fourth floor (complete with Orwellian hissing gas fire), John Sibbald developed a whole new department. However, there was as little interest in classical books then as there now is in theology.

Right:John Sibbald training to be an Anglican priest.

Right:John Sibbald training to be an Anglican priest.

‘My approach was to release books from obscurity by setting them in their cultural and historical context. I started buying wherever I could, although I never attended an auction – the actual bidding was dealt with by Dawsons; I would view and suggest what to pay, and purchases were delivered to Cambridge by post. Because my field was unconsidered, even despised, I was also able to buy very profitably from other booksellers’ catalogues. Reviewing these in order to get orders in quickly was my first task of the day. While there were few booksellers working in my field, a number of catalogues were always exciting to receive. I am thinking of E.K. Schreiber (New York), Erasmus (Amsterdam), Jorg Schaffer (Zurich), E.P. Goldschmidt (London), Ludwig Rosenthal (Hilversum), Gilhofer & Ranschburg (Lucerne), William Salloch (New York), and Diana Parikian (Oxford). Alex Rogoyski (London), too, was an inspiration, though I don’t ever recall seeing a catalogue, as such, from him.’

The very first task he was set at Deighton Bell illustrated how fascinating a challenge his job would be. Among some items a bookseller wanted to buy, there was a small volume of Latin poetry.

‘I priced it at nine pounds and the bookseller turned it down. However, a few weeks later I came across an Italian translation and commentary which made me revisit it. Its true significance came into focus. What had been refused as too expensive at nine pounds, was the first edition of Santorio’s De Statica Medicina (Venice, 1614). Santorio was the founder of the physiology of metabolism. He placed his worktable, bed and all that he needed for existence on a specially constructed weighing machine and literally weighed everything that went in and out over a period of thirty years.’

The results of what has been described as ‘one of the most courageous affirmations of experimental medicine’ were published in poetic form.

‘The first edition turned out to be of staggering rarity, with only two imperfect copies traceable (Welcome and the bookseller L’Art Ancien’s catalogue of Early Books on Medicine). It was not in the BM, the Biblioth

èque Nationale, Library of Congress, Surgeon General, Osler, Cushing or Waller. The time spent on research was more than justified by my selling it for the rather improved figure of £1900. Incidentally, it reappeared in 1998 at Christie’s, where it made $63,000.’

On another occasion, he deciphered faint pen scratchings on the vellum cover of a commentary on the works of Cicero, as ‘D. Montani’. This turned out to be a volume from Montaigne’s library.

Andrew Fletcher’s fine collection was rich in association copies and included works once owned by many of the great humanist scholars of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. By the time of his death in 1716, his ms catalogue (now in the National Library of Scotland) listed 6000 titles.

Cartoons (left and below):Cambridge chat by John Sibbald.

Cartoons (left and below):Cambridge chat by John Sibbald.

‘My catalogues were issued against a background of a revival of interest in the history of classical scholarship and study of textual transmission, typified in such works as Kenney’s The Classical Text, Reynolds and Wilson’s Scribes & Scholars and Pfeiffer’s History of Classical Scholarship 1300-1850. Two books which particularly inspired my endeavours were Sandys’ monumental History of Classical Scholarship and E.P. Goldschmidt’s Mediaeval Texts and Their First Appearance in Print, of which I have the late Professor Denys Hay’s copy. There was a growing appreciation of the scientific value of some texts, in particular of some mediaeval commentaries. One of my customers was Dr Denis O’Brien of Caius College, who divided his time between Cambridge and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris, where he worked on theories of weight in Democritus, Plato and Aristotle. Looking back, it now seems quite incredible as to what it was possible to assemble between the covers of one catalogue.’

Cambridge in the 1970s was a wonderful place to be if your were interested in the printed book.

‘The 450th anniversary of the arrival of printing in Cambridge, where John Siberch set up his press in 1521, was marked in 1971. Brooke Crutchley was then the University Printer presiding over the publication of scholarly books, many of great typographical distinction, as well as issuing his inimitable series of Christmas books. Products of equal distinction and innovation poured forth from Will and Sebastian Carter’s Rampant Lions Press. The annual Sandars lectures was eagerly anticipated:the Cambridge Bibliographical Society attracted speakers of great distinction, as did the Edward Capell Society and, on occasion, the Cambridge Library Group, of which I was secretary for a couple of years. Heffers, Galloway & Porter, Bowes & Bowes, David’s and Deighton Bell provided a seemingly endless array of bibliophilic temptations to suit every taste and pocket.’

The city was home to some of the most illustrious bibliographers of the time – J.C.T. Oates, F.J. Norton, A.N.L. Munby and Philip Gaskell, author of New Introduction to Bibliography. John Sibbald regularly attended his ‘awe-inspiring’ lectures on bibliography in the Syndics’ Room in the University Library.

Cambridge was full of great literary characters, and was haunted by those of the past.

‘Patricia Huskinson, who managed the shop part of Deighton Bell, used to point out to anyone interested, the chair on which Houseman used to sit on his visits there. One sometimes felt that Dr Leavis was lurking, ready to pounce on any corrupt use of English. I often used to encounter the economist Geoffrey Keynes searching for sepia coloured ink. And little did I think as I saw E.M. Forster vanish down the passage by the Senate House that I would later share a flat with some 5000 of his letters and his biographer, the writer and critic P.N. Furbank.’

College hospitality was generous, though high tables could be ‘bitchy’.

‘I remember hearing C.P. Snow, who at the time I think was being considered as a Master for Churchill, being dismissed as ‘Neither a particularly good novelist, nor even physicist.’ Or, summing up the novelist Simon Raven, ‘I like Simon. No nonsense about him. Good honest, straightforward vices:boys, girls and drink.’ I also recall an aged St Catharine’s don across the table enquiring, ‘crystalographer?’, to which my reply of ‘shop assistant’ seemed something of a let down. On apparently being addressed by another don as ‘whore’s delight’, I was considering whether I should give my interlocutor a punch on the nose or congratulate him on his discernment, when I realised Whore’s Delight was the name of the snuff he was offering me.’

Among John Sibbald’s customers was the late Tom Driberg, who started to take an interest in rare books on his retirement from the House of Commons.

‘He once turned up with some highly obscene poems in manuscript by Auden, asking for them to be photocopied as he no longer had access to a photocopying machine. After lunch I momentarily lost him in the crowd in Sidney Street where he had lingered to engage a newspaper boy in conversation. As I put him into a taxi for the station, tucking under one arm his latest acquisition (the Koberger edition of Henricus de Herpf’s Speculum Aureum, Nuremberg, 1481), he expressed the wish that under the other arm he could be taking away the news vendor. The taxi roared off before I could offer an appropriate response.’

‘He once turned up with some highly obscene poems in manuscript by Auden, asking for them to be photocopied as he no longer had access to a photocopying machine. After lunch I momentarily lost him in the crowd in Sidney Street where he had lingered to engage a newspaper boy in conversation. As I put him into a taxi for the station, tucking under one arm his latest acquisition (the Koberger edition of Henricus de Herpf’s Speculum Aureum, Nuremberg, 1481), he expressed the wish that under the other arm he could be taking away the news vendor. The taxi roared off before I could offer an appropriate response.’

In 1977 John Sibbald, now married, returned to Edinburgh where he worked briefly for the firm of R. and J. Balding. After a spell at the National Library of Scotland he became Deputy Librarian at the Advocates’ Library where he later took over as Librarian. An important part of that role was to introduce modern technology to the Bar. In 1988 he set up his own business, Professional Library Services, which continues to flourish.

‘There are very few librarians in Scottish law firms, although all lawyers are basically information processors. Most of my clients are law firms. I was chairman of the Scottish Society for Computers in Law for five years, and became its first honorary Vice-President; I now edit the E-Law Review, a journal devoted to electronic law. I’m also on the advisory boards of the Joseph Bell Centre for Forensic Statistics and Legal Reasoning, and the Scottish Research Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Technology at Edinburgh University.’

John Sibbald is involved in developing the Virtual Hamilton Trust, due to be lanched as part of the SCRAN website:a consortium of scholars have come together to recreate – virtually – Hamilton Palace, which was demolished in 1936. A substantial pilot project has just been completed, undertaken with the Royal Commission on Ancient Historical Monuments of Scotland as the lead body, and with National Opportunities funding.

When he stepped into the breach at auctioneers Lyon and Turnbull (Peter Nelson is on leave following an illness), John Sibbald’s grounding in cataloguing rare books at Deighton Bell came flooding back. He is very much enjoying adding this new string to his bow.

With gentle demur, he describes himself as a man without ambition.

‘If I had one, it was to be a clergyman, but that came and went and I’ve been casting around ever since. I’ve been very lucky. Doors have always opened for me. Perhaps a wiser man wouldn’t have gone through some of them, but I’ve always wanted to know what’s on the other side.’

Catalogue 132 (1971) contained eighty-four items of which thirty-five were printed before 1500 and included St. Augustine’s Enchiridion de Fide. (Cologne, Zel, c. 1467), Jacobus de Bergamo’s De Claris Selectisque Mulieribus (Ferrara, Rubeis, 1497), the Nuremburg Chronicle (Nuremburg, Koberger, 1493), the first edition of Agricola’s De Re Metallica (Basle, Froben, 1556), Archimedes (Basle, Hervagius, 1544) and Vesalius De Humani Corporis (Basle, Operinus, 1555).

Catalogue 140 (1972) contained no less than twenty-seven editiones principes of Greek and Latin authors (including Dionysius of Halicarnus, Epictetus, Hermes Trisgemistus, Homer, Lucian, Photius, and Procopius). For good measure it also included the Foulis Press Homer, Pine’s Horace, the Baskerville Terence and the Ibarra Sallust.

Catalogue 148 (1974) offered over 400 items of Greek and Latin authors and commenced with over seventy items on or by Aristotle, of which some forty-five were printed before 1600 and four before 1500. Also included was the Jenson Pliny (Venice, 1472), the Strassburg Ptolomy (1513), Mela’s Cosmographia (Venice, 1495) and the Mainz Bible of 1472.

Catalogue 209 (1977) The Classics section opened with the editio princeps of Aelian (Rome, Blado, 1545) and included twelve other editiones principes of Greek authors; Parr’s copy of Aristotle’s Posteriora Analytica (Venice, heirs of Aldus, 1534) with the ms. notes of Richard Porson; the first book by the first King’s printer in Greek in France (Aristotle, Rhetorica, Paris, Neobar, 1539); the first book to be printed entirely in Greek in England (John Chrysostom, Homiliae Duae, London, Cheke, 1543); an example of the first Greek type cut in France (Lactantius, Opera, Paris, Petit, 1513); and one of the first books to be printed almost entirely in non-ligatured Greek (Pausanias, Leipzig, Fritsch, 1696). Amongst other rarities, the catalogue also offered the first printing of the Florentine Pandects (Florence, 1553), Montfaucon’s Palaeographica Graeca (Paris, 1708), Estienne’s magnificent edition of the Poetae Graeci (Geneva, 1566), and Scaliger’s famous exposition of the physics and metaphysics of Aristotle, the Exotericarum Exercitationum (Frankfurt, heirs of Wechel, 1582). The catalogue also contained some thirty-six works by or commentaries on Aristotle, for the most part printed before 1600. To be able to assemble so many important Greek books within the confines of one catalogue was tremendously exciting and, of course, wholly appropriate to Cambridge, where the Greek type made its first appearance in England in 1521.

Copyright Jennie Renton 2005.

Comments