Pictish studies

Pictish Studies

My first introduction to the Picts came in the flickering firelight of a West Highland school. I was raised in Glencoe, attending the primary school there. In those days (the early 1950s) electricity had not yet come to the village. The single schoolmistress had to teach all subjects to all age-groups; history came late in the afternoon, hence many a lesson was conducted in the gathering dusk, under the fitful illumination of a paraffin lamp which was often outshone by the roaring open fire. It was here that I first learned

My first introduction to the Picts came in the flickering firelight of a West Highland school. I was raised in Glencoe, attending the primary school there. In those days (the early 1950s) electricity had not yet come to the village. The single schoolmistress had to teach all subjects to all age-groups; history came late in the afternoon, hence many a lesson was conducted in the gathering dusk, under the fitful illumination of a paraffin lamp which was often outshone by the roaring open fire. It was here that I first learned

how in ancient times the Picts and the Scots held the might of imperial Rome at bay, and, after the departure of the legions, saw off attempts by the Angles to make the whole island their own.

Of course, history as presented in a primary school text-book tends to be somewhat over-simplified, although in those days it would have been difficult to have found any alternative information on the Picts, mostly presented from an archaeological viewpoint in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, was somewhat indigestible. It was also problematic in that it proved extremely difficult to identify a Pictish site, and if anything it was worse for historians because of the total lack of Pictish literature (apart from very late King-lists) and the paucity of literary references in general, as demonstrated by Alan Anderson in his two-volume work Early Sources of Scottish History of 1992.

Almost alone among Victorian studies as a work of reference was William Skerne’s Chronicles of the Picts, Chronicles of the Scots, and other Early Memorials of Scottish History (1867). Though there is much within its covers which the reader should treat with caution. Most other books in this vintage about the Picts are highly fanciful, and probably the kindest thing that can be said about them is that they are entertaining rather than instructive. They are certainly of interest to bibliophiles, though of little help – and at times of considerable hindrance – to serious students of the Picts.

If a straightforward approach to Pictish history was proving something of a difficult hurdle, then a different course might provide the key. It centred around the most visible reminder of this vanished society -the carved standing stones which were left over much of Pictland, (which comprised the greater part of northern and eastern Scotland), close on 200 of which still exist. They are remarkable for their quality of craftsmanship, command of line, ornate decoration, and especially for their enigmatic symbols. This unique corpus of evidence hinted at various aspects of the nature and structure of Pictish society, yet even today most of its secrets remain locked within their splendid artistry. A scheme was initiated to create a comprehensive illustrative record of all Pictish stones, for the majority at that time were still standing as field monuments, gradually succumbing to the weathering forces of a millennium and more.

Such a notion had been developing throughout the nineteenth century. IN 1814, the historian John Pinkerton called for an illustrated volume of all early medieval sculptured stones in Scotland. He was critical of early eighteenth century attempts, especially regarding the quality of those illustrations.  Those of Thomas Pennant were ‘too diminutive’, likewise those of Charles Cordiner, ‘whose representations cannot be trusted, his imagination being strangely perverted by some fantastic ideas’, whiel those of Alexander Gordon were ‘too rude and inaccurate’. This theme clearly required a more disciplined approach. The first systematic study was the Ancient Sculptured Monuments of the Country of Angus by Patrick Chalmers, published in 1848. Although confined to one county, it did include a large proportion of all known Pictish stones, and Chalmers was a skilled and respected antiquarian. The book was welcomed – though not for its size: it consisted of imperial pages measuring 22 x 30 inches making it difficult to use and impossible to shelve.

Those of Thomas Pennant were ‘too diminutive’, likewise those of Charles Cordiner, ‘whose representations cannot be trusted, his imagination being strangely perverted by some fantastic ideas’, whiel those of Alexander Gordon were ‘too rude and inaccurate’. This theme clearly required a more disciplined approach. The first systematic study was the Ancient Sculptured Monuments of the Country of Angus by Patrick Chalmers, published in 1848. Although confined to one county, it did include a large proportion of all known Pictish stones, and Chalmers was a skilled and respected antiquarian. The book was welcomed – though not for its size: it consisted of imperial pages measuring 22 x 30 inches making it difficult to use and impossible to shelve.

The next advance came with the publication of a more wide-ranging work, The Sculptured Stones of Scotland by John Stuart, issued in two volumes in 1856 and 1867, an interdisciplinary study, with extensive references to historical sources, associated topographical and archaeological material, and much art-historical analysis.

The next major development stemmed from the delivery of the Rhind Lectures to the Society of Antiquaries in 1879 and 1880, and their publication in 1881, by Jospeh Anderson. He adopted a rigorously scientific approach, building upon a groundwork of exact knowledge based on the collection of as complete a store of data as possible; only then could valid deductions be made. Anderson’s two-volume work, Scotland in Early Christian Times, covered an enormous range of material, among which he included the artistry and symbolism of the Pictish stone-cut designs. This encouraged a subcommittee of the Society of Antiquaries to issue a report in 1890 recommending the creation of a complete register. No special provision had been made for a Scotland in the Ancients Monuments Protection Act, and so the moral responsibility for overseeing the protection of the Pictish stones fell on the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Tow men then embarked upon this mighty project: J. Romilly Allen compiled a classified, descriptive, and illustrated inventory of all the Pictish stones then known, and such other material as existed, while Joseph Anderson undertook an artistic analysis of Pictish designs. Their weighty volume, The Early Christian Monument of Scotland, which remain the ‘Bible’ of Pictish Art, was published in 1903, but it was very expensive to produce, and a limited edition of only 400 copies was printed. It has long been out of print, and, with demand growing, second-hand copies have been fetching very high prices. Now, ninety years on, a reduced-scale two-volume reprint has been published by the Pinkfoot Press.

With the original publication of ECMS Pictish art at last received a treatment worthy of it, yet the Picts themselves remained very much in the shadows for the next half-century. Indeed, they did not receive a scholarly appreciation until the publication by Nelson in 1955 of The Problem of the Picts, a multi-author book edited by Frederick Wainwright. Some parts may be a little dated now, but it did provide a very thorough consideration of the issues. It became a classic of its kind, but it also has been long out of the print, and the 1980 Melven Press reprint is, likewise, hard to come by.

A different approach was adopted in a booklet published by HMSO in 1964 entitled The Early Christian and Pictish Monuments of Scotland by Stewart Cruden. Following a brief introduction to the subject, he provided a catalogue of the stones in the two specialist museums run by his department (then known as the Ministry of Public Buildings and Woks) at Meigle and St. Vigeans.  This little volume has also been out of print for a long time, and surely a reprinting, or better still a rewriting, is very much overdue. A similar approach, though in much broader social and historical terms, was adopted for the booklet Foul Hordes: the Picts in the North-East and their Background, written by Ian Ralston and Jim Inglis to accompany an exhibition in the Anthropological Museum at Aberdeen University in 1984. Two other catalogues have been produced: Dark Age Sculpture in the National Museum by Joanna Close-Brooks and Robert Stevenson (HMSO, 1982), which deals with Pictish stones (and Scottish, Anglian, and Norse ones also); and Pictish Stones in Dunrobin Castle Museum by Joanna Close-Brooks (Sutherland Trust and Pilgrim Press, 1989). All these catalogues are attractively produced and well illustrated. A major step forward in Pictish studies took place in 1967 when Thames and Hudson published The Picts by Isabel Henderson as volume 54 of their Ancient Peoples and Places series. The author is a renowned scholar and respected historian, and this book rapidly achieved the status of ‘the standard work’. Interest, continuing to grow, was further fostered by the 1971 BBC television series Who Are the Scots? Isobel Henderson wrote the Pictish chapter in the accompanying book, going back to Wainwright’s volume for her title. Another educational publication was The Kingdom of the Picts by Anna Ritchie (Chambers, 1977), which was aimed specifically at schoolchildren.

This little volume has also been out of print for a long time, and surely a reprinting, or better still a rewriting, is very much overdue. A similar approach, though in much broader social and historical terms, was adopted for the booklet Foul Hordes: the Picts in the North-East and their Background, written by Ian Ralston and Jim Inglis to accompany an exhibition in the Anthropological Museum at Aberdeen University in 1984. Two other catalogues have been produced: Dark Age Sculpture in the National Museum by Joanna Close-Brooks and Robert Stevenson (HMSO, 1982), which deals with Pictish stones (and Scottish, Anglian, and Norse ones also); and Pictish Stones in Dunrobin Castle Museum by Joanna Close-Brooks (Sutherland Trust and Pilgrim Press, 1989). All these catalogues are attractively produced and well illustrated. A major step forward in Pictish studies took place in 1967 when Thames and Hudson published The Picts by Isabel Henderson as volume 54 of their Ancient Peoples and Places series. The author is a renowned scholar and respected historian, and this book rapidly achieved the status of ‘the standard work’. Interest, continuing to grow, was further fostered by the 1971 BBC television series Who Are the Scots? Isobel Henderson wrote the Pictish chapter in the accompanying book, going back to Wainwright’s volume for her title. Another educational publication was The Kingdom of the Picts by Anna Ritchie (Chambers, 1977), which was aimed specifically at schoolchildren.

1985 provided a special occasion to get to grips with a very special Pictish event, because it was the 1300th anniversary of the Battle of Dunnichen, in which the Picts routed the Northumbrians and thereby laid the foundations of the Scottish nation. Such an event could not be allowed to pass uncelebrated, and so I laboured away for many months beforehand, but the ‘big guns’ in the world of Scottish history did not, and so it was with some embarrassment but soon after with a sense of elation that I became the sought-after ‘expert’ on the subject, being called upon to deliver a lecture to the Forfar and District Historical Society, to lead an outing of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, and to give three interviews for radio and make two television presentations.

The most lasting of my contributions to that event was a booklet, Nechtansmere 1300: A Commemoration, for the Forfar Society (Nechtansmere being the English name for the battle, which for some illogical reason was widely used until recently). Just as this went out of print in 1991, shocking news broke. A firm of local quarry-masters had applied to blast away Dunnichen Hill, without which our ability to appreciate the visual explanation of the Picts’ battle strategy would be destroyed. Showing commendable enterprise the Pink-foot Press (located within sight of the Hill) promptly produced a rewritten, redesigned version of my booklet, retitled The Battle of Dunnichen, which made its contribution to the Save Dunnichen Hill campaign. To date, the hill remains unmolested.

Most new work on the Picts continued to appear in learned journals, some of them rather obscure. Occasionally papers were gathered together in volumes, such as Pictish Studies: Settlements, Burial, and Art in Dark Age Northern Britain edited by J. Friell and W. Watson: British Archaeological reports, British Series 125, 1984; and The Picts: a new look at old problems edited by Alan Small, Dundee, 1987. While some of these papers were useful, their overall contribution was patchy. What the subject badly needed was a new approach, and happily this appeared in several refreshing guises.

In 1988 the Pictish Arts Society was founded with a very broadly-based membership, eager both to build upon the past and to adopt novel approaches to Pictish studies. Sacred Stones, Sacred Places was written by one of its founder members, Marianna Lines. The Society’s thrice-yearly Journal has quickly gained a sound reputation. Another landmark was reached in 1989 with the publication of Picts by Anna Ritchie, one of an HMSO series dealing with various aspects of Scotland’s history and culture. The work of an experienced archaeologist and respected antiquarian, this really is a little gem, not only interestingly written, beautifully produced, and superbly illustrated, but also very reasonably priced. I was invited to write a detailed appraisal of it, which appeared as the Pictish Arts Society Occasional Paper No. 1.

Two other events occurred in 1989. A booklet entitled The Pictish Trail by Anthony Jackson was published by the Orkney Press. It opens with his view of the purpose of the Pictish symbols (a simplified version of his 1984 book The Symbol Stones of Scotland from the same publisher), and goes on to give brief details of eleven trails which lead to Pictish stones between Edinburgh and Golspie. In that year, too, Groam House Museum at Rosemarkie, which had developed into a Pictish centre, initiated a series of annual lectures, published them in the year following. The first, The Art and Function of Rosemarkie’s Pictish Monuments by Isabel Henderson, set a high standard. Pictish studies is indeed in a healthy situation, with new publications coming thick and fast. This article is not intended to provide a complete survey of the literature (which it does not), but more to indicate the range of material available. The latest is a handsome, if pricey, production by Alan Sutton Publishing intriguingly entitled The Pcits and the Scots by Lloyd and Jenny Laing. Having examined it under the steadfast glare of an electric light, the subject seems much more complicated than it was back in Glencoe forty years ago. For me, Pictish studies has come full cycle.

© Graeme Cruickshank

From the Scottish Book Collector archives.

For more information contact the Pictish Arts Society: www.pictart.org

Images:

Graeme Cruickshank is photographed holding a copy of his booklet, The Battle of Dunnichen, published by The Pinkfoot Press in 1991. He is pictured at Dunnichen, three miles south-east of Forfar, beside a fibreglass replica of the Dunnichen Stone. (The actual stone was removed to Dundee museum in 1971, to the great dissatisfaction of the local community; the replica was erected in 1977.) Photo: Kim Cessford Studio, Forfar.

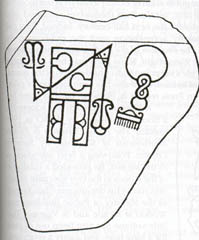

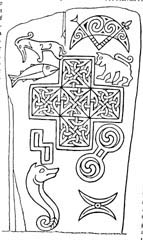

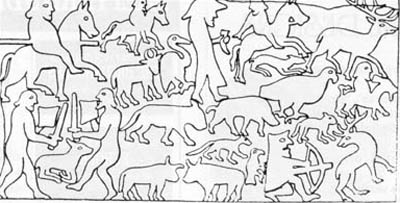

The line drawings are taken from The Early Christian Monuments of Scotland by J. Romilly Allen and Joseph Anderson. The first picture is of Clynemilton no. 2 stone (Dunrobin Castle Museum), the second of Ulbster Stone (Thurso Museum), and the third of a panel from the Shandwick Stone field monument (Easter Ross).

Comments