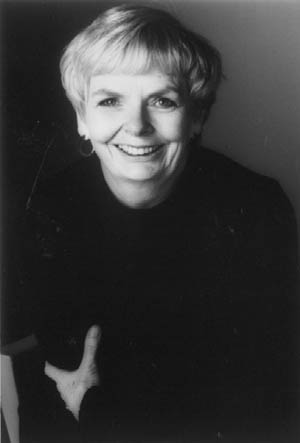

Carol Shields

Carol Shields

How did you feel when your first book was published?

The first book I had published was a novel. I was living in Ottawa, which is a big city but a small village too, and the local bookstore had their windows filled with my book. I couldn’t walk past because I was so embarrassed. It was such exposure, and there’s a fragile period when the major reviews come out. I had only had little collections of poetry published before, but they were done so quietly. People talk about books as being like their children and there is a sense of that. I remember the publication dates of all my books, just as I remember my children’s birthdays.

The first book I had published was a novel. I was living in Ottawa, which is a big city but a small village too, and the local bookstore had their windows filled with my book. I couldn’t walk past because I was so embarrassed. It was such exposure, and there’s a fragile period when the major reviews come out. I had only had little collections of poetry published before, but they were done so quietly. People talk about books as being like their children and there is a sense of that. I remember the publication dates of all my books, just as I remember my children’s birthdays.

Did you write from an early age?

I was always a literary kid. I read a lot – rubbish along with the good stuff. Even as a young child I was immersed in language. I used to write little poems, I wrote the school play and I wrote for the school newspaper. I did all those kind of things that the literary girl does (there’s usually one or two!). Then, in my twenties, I stopped for almost ten years, when I had my children. I was reading but doing very little writing: just a handful of short stories, not very good ones, which were broadcast rather than printed. But I didn’t have the time, and it took me a while to figure out what I wanted to write about. I wasn’t just waiting around until the children went to school – I don’t know what I thought would do. It just happened in very small increments. I started getting the odd poem published, then a publisher asked me if I had enough poems to make a book, and I said ‘how many do you need?’ and he said ‘about fifty,’ and I said, ‘I don’t have fifty, but maybe I will in six months.’ That’s how it happened. Other people’s encouragement helped a lot.

Do you collect books yourself?

Yes, I do. I wrote a dissertation on a woman called Susanna Moodie, who was a Canadian pioneer, so I started collecting early editions of her work. I don’t have a first edition of her most famous book, but I could have had one. I keep thinking I should have bought it that day! But now the price is astronomical. So I changed to collecting books by Canadian women, writing between 1890 and 1910. You have to limit what you’re after, and I guess I was interested less in the literary value and more in the Canadian imprint, which makes books a little more collectable. I was also interested in feminism and what women were writing about at that time. It was a real period of change, just before women got the vote. Sometimes I will buy a book outside that period, and I always think I’ll sell it when I find something else more appropriate. But I never end up selling anything. I’m a very low budget collector, but I do have some nice books. I found a rare imprint in a second-hand furniture store and bought it for $3. The store owners didn’t know the value of it, and it was such a find. The thrill of the collector – I understand it perfectly!

I love the way books used to be produced – they were much more solid and lasting.

So do I. That’s why, in one of my books, The Republic of Love, I wanted a frontispiece with a line of dialogue beneath it. I felt that the look of The Stone Diaries should gesture towards the idea of biography, with photographs in the middle. Old books always had pictures in them – every thirty pages there’d be an illustration – but for some reason we’ve stopped doing it. I don’t know why. Maybe for reasons of expense, or perhaps people feel grown-ups don’t need pictures. In Larry’s Party, I wanted a picture of a tiny maze at the beginning of each chapter – I just thought it would give the book a little extra dimension. When I wrote Mary Swann, my plan was for people to come across a little crumpled photograph, which would be put somewhere in the pages, at random. The publishers said, ‘But how will we get the pictures into the books?’ and I said, ‘My daughters and I will sit and put them in.’ I thought finding a photograph like that would be such a wonderful surprise, but they just couldn’t see it. I must persevere with the idea for the next book. I once found a photograph in a library book and I thought, ‘I’m going to keep this, this was meant for me’. In fact, it appears in The Stone Diaries – it’s the photo of a family leaning against a wall – and I actually heard from some of the people in it, after the book was published.

So do I. That’s why, in one of my books, The Republic of Love, I wanted a frontispiece with a line of dialogue beneath it. I felt that the look of The Stone Diaries should gesture towards the idea of biography, with photographs in the middle. Old books always had pictures in them – every thirty pages there’d be an illustration – but for some reason we’ve stopped doing it. I don’t know why. Maybe for reasons of expense, or perhaps people feel grown-ups don’t need pictures. In Larry’s Party, I wanted a picture of a tiny maze at the beginning of each chapter – I just thought it would give the book a little extra dimension. When I wrote Mary Swann, my plan was for people to come across a little crumpled photograph, which would be put somewhere in the pages, at random. The publishers said, ‘But how will we get the pictures into the books?’ and I said, ‘My daughters and I will sit and put them in.’ I thought finding a photograph like that would be such a wonderful surprise, but they just couldn’t see it. I must persevere with the idea for the next book. I once found a photograph in a library book and I thought, ‘I’m going to keep this, this was meant for me’. In fact, it appears in The Stone Diaries – it’s the photo of a family leaning against a wall – and I actually heard from some of the people in it, after the book was published.

You examine a lot of everyday objects in Dressing Up for the Carnival – mirrors, windows, a scarf, keys – was it a conscious decision to meditate on certain ordinary items like that?

No, not really. With the Keys story, I was just looking at my key ring one day and wondering how I happened to get so many keys – I used to just have two. So I wrote about them simply as a physical article. Keys do seem, more than most things, to measure the complexity of your life.

It seems as if you were having a lot of fun with these stories, ‘Absence,’ for instance, where you omit the letter i throughout, to illustrate the story of a woman whose typewriter is missing that letter. Was it difficult writing without an i?

Actually, not very. Someone in France has written a whole book without

an e, and that’s especially difficult in French because of all the feminine endings! But I did have a broken a on my typewriter once, and I remember Don, my husband, saying, ‘couldn’t you write something without an a?’ I just thought a missing i would be more interesting, as it implies more than just a missing letter.

Do you find that playing games with words helps when you’ve become a bit stuck with writing?

Yes. I wrote my first book of short stories, Various Miracles, when I was stuck on a novel. It gave me some time off and a way to look at other narrative strategies. They were all quite different as there were a number of things I wanted to do with words.

Do you feel emotionally different towards writing novels and stories?

Yes, I feel more playful writing stories. I can do all kinds of things with them, whereas with a novel I’m committing myself to a particular tone or voice or direction – a certain architecture, anyway. With stories you can have an idea and spin it around for as long as it will stay aloft. I feel that I’m tap-dancing when I write stories. I can get both feet off the ground.

Would you want to write a novel that had some of the more surreal qualities of your stories?

I don’t know. I don’t know how you feel about the South American magic realist writers, but I haven’t been terribly engaged by them. Most women I know haven’t been. It’s a pretty hard tone to sustain, and it also leads to gross simplifications and reductions that I’m not willing to accept. I remember reading one of Marquez’s novels which starts off with a couple who have lived together for eighty years and have never had a cross word between them. And I thought, ‘Oh, come off it! Do you really expect me to engage with this?!’

Do you mull over ideas for a long time before you start a novel?

Well, I wrote my first, unpublished one in about six weeks. It was very short and didn’t quite work. But I got wonderful rejection letters which all said the same thing: the narrator’s voice and the main character’s voice were too far apart. So for the next novel, Small Ceremonies, I kept the voices closer together, wrote two pages every day, and finished it in nine months. I have never been able to write a novel that fast since. I figured out the structure on little box-cards, to remind me to put certain scenes in and not to leave out a character for a hundred pages, and then I just let it go where it wanted. Having a framework helped me, and I always do that now. Otherwise I’d get lost in the morass.

I’m intrigued, in The Stone Diaries, with the way Daisy Goodwill talks about herself in the third person. Is that just something that felt natural, or was it a deliberate decision?

It didn’t just happen. I worried that the voice might be confusing, so when I finished I went right through to check that all the connections were closed; and to make sure it was an easy slide from one voice into another. Also, there is simply the idea that sometimes you do see yourself in the third person, at a distance.

Does your work with biographies influence the way you construct a plot?

I’ve written quite a bit about other people writing biographies, but I’ve only written one myself, about Jane Austen. It’s part of a series, mainly by novelists rather than professional biographers, and when the editors offered me Jane Austen I couldn’t resist. But I don’t think biography is my thing: I found it a little bit tedious, even though I’m very interested in Jane Austen’s life. It was a bit of a chore, putting facts together and not having room to embellish. With my own writing, I’m interested in the idea of the arc of human life, as a plot in itself. It’s the only plot I’m really interested in. Plots seem quite contrived things, and I don’t think writers can get away with them in the way that they once did. I think books have changed in that sense. People aren’t willing to be so manipulated any more, particularly in that old pattern.

Is that a post-modernist thing, do you think?

I think it’s to do with women’s writing. Women don’t see structure as being very useful to their lives – that sort of rising line of action and then climax. I don’t think women’s lives work that way. I wrote an early novel where I felt I wasn’t doing enough with plot, so I contrived one, and I regret that. I just said, ‘I’ll never do that again’.

I once went to a playwrights’ workshop where the man running it said, ‘you must have a theme from the very start,’ which completely put me off!

Yes! I wrote a play once at a workshop and they kept saying, ‘you have to put more tension in this.’ The play was about four women and how close they were. The workshop leader wanted two of them to have a quarrel and then a reconciliation, but I felt that the tension lay in the value of their lives, not in some old-fashioned feud. I thought that was a very bad piece of advice. There is a great deal of conventionality at the heart of some writing.

Do you do a lot of research before you begin a novel?

No, I never do. In fact, whenever I have a student who says, ‘I’m going to start my novel as soon as I finish my research,’ I always know they’re never going to write it. I don’t think it works that way at all. I look for what I need as I go along. I will look things up or go to the library or buy a book. I had to buy a book on hedges when I was writing Larry’s Party and it had everything I needed. I also bought some books on mazes. With The Stone Diaries, I used old newspapers quite a bit, just to pick up a few facts and get a sense of the time in which it was set. And I did eventually buy myself a dictionary of slang because I wanted to use certain speech-tags from the early part of the twentieth-century and I wanted them to be right. I was always asking friends if they knew certain expressions. I remember looking up ‘licketty-split’, because my mother used to say that, whereas my children don’t. There must have been a time when it passed out of common usage.

I was interested in Magnus Flett, one of your characters in The Stone

Diaries, being an Orcadian, and I wondered if you had any family connections with Orkney?

I don’t have any connections that I know of, but when I started to look into the stone-quarrying history of Manitoba, I found that most of the stone-workers had come from Orkney. Then I realised that many people had come from Orkney to Manitoba with the Hudson’s Bay Company, and so I felt I had to go and see the island. I had already been to the Hebrides and at first I thought I would use my knowledge of those islands when I was writing the book. But Orkney was so clearly different, and so I was glad I went. It was a wonderful trip for us. There’s so much to see. That’s when I changed Magnus’s surname to Flett. I had another name for him, but it didn’t appear in the phonebook on the island, while Flett was on every gravestone – and then I realised there were also a lot of Fletts in Manitoba.

Do you think Canadian writing has similarities with Scottish writing, in

the sense that there is a lot of connecting history between the two

countries?

Scotland and Canada share a similarity in being at the north of much larger powers; and culturally, there are links. So I think it’s not a bad parallel, really. Writing has always come from the edge, not the centre, and both Scotland and Canada are at the edge. And, of course, women are at the edge of the edge. Women writers in Canada have tended to be more prominent, although, book by book, there are still far more by men, reviewed by men, and published by men.

I wonder if that’s to do with the way writing is marketed – men’s writing can tend to be more themed, more conventionally about something. Women’s writing is perhaps less easy to pigeonhole.

Except as women’s writing. Or domestic fiction – that’s the one I hate!

How do you cope with the publicity side to being a well-known writer? Isn’t it funny to be marketed as a thing?

Yes! And you’re always afraid that people will be disappointed when they meet the thing. You’ve read the book, now here’s the body.

One of the characters in Dressing Up for the Carnival finds herself in that position, feeling very ordinary in this rather extraordinary situation.

Yes. People are always telling you that you shouldn’t write about writers, and I guess mainly I haven’t, but I just felt I wanted to write about that whole situation. It’s like people saying, ‘don’t write about university life because no-one’s interested in that,’ but if it’s part of your life, why shouldn’t you write about it?

Which writers do you particularly enjoy?

Alice Munro is a remarkable writer. In fact, I’ve just written to her because there was a story of hers in the New Yorker recently that I thought was so wonderful. It’s about a long marriage, and you don’t often read about that. It was so tender. I love John Updike and Cynthia Ozick. She’s got a real toughness to her. I think Lorrie Moore is great, her humour is so black. And Jane Austen, of course, I’ve always been interested in Jane Austen. Some of Martin Amis – but not his underworld stuff. Middle-period Iris Murdoch. Henry James, Grace Paley – I keep feeling I have met her because I have heard her interviewed on the radio and that voice is so surprising – her New York growl. Her stories always have so many surprises. I belong to a women’s book discussion club, but the other night I was invited to a men’s book club, and I came away thinking that men are even more different than I already realised! They read mostly male writers and only one woman writer per year, which is the exact opposite of what we do in our club. They also interrupt each other a lot and don’t want to know anything about each other’s work or children.

How do you go about your work as a full-time writer?

Virginia Woolf said – I think in Three Guineas – that writers don’t need the stimulation of travel, they need under-stimulation, the same things around them, and sitting down at the same time every day to write. It just spoke to my heart.  We lose so much of the narrative that floats around us – it just slips through our fingers. There are so many stories that haven’t been told – during the period when people were illiterate, for example; or the stories that women haven’t been able to tell; or the stories that you can’t tell because they’re too strange for anyone to believe.

We lose so much of the narrative that floats around us – it just slips through our fingers. There are so many stories that haven’t been told – during the period when people were illiterate, for example; or the stories that women haven’t been able to tell; or the stories that you can’t tell because they’re too strange for anyone to believe.

Comments