illustration

The Art of Ivan Bilibin

Recently I met one of the few fortunates to possess several first editions of books illustrated by Ivan Bilibin; he also had an early-twentieth century publicity notice advertising Bilibin’s work, issued by Jenners store in Edinburgh. In mid-covet, I acquired a 1981 illustrated Pan edition of a study of Bilibin’s life and work by Sergei Golynets; even if I would never actually possess any of the original publications, this well-illustrated and documented study opened up to me the world of Ivan Bilibin. An internet trawl of Abe Books showed (on that particular day) many reprints, but actual first editions of tales illustrated by Bilibin on offer from only two booksellers, Aleph-Bet Books in the USA and Politikens Antikvariat in Denmark.

Recently I met one of the few fortunates to possess several first editions of books illustrated by Ivan Bilibin; he also had an early-twentieth century publicity notice advertising Bilibin’s work, issued by Jenners store in Edinburgh. In mid-covet, I acquired a 1981 illustrated Pan edition of a study of Bilibin’s life and work by Sergei Golynets; even if I would never actually possess any of the original publications, this well-illustrated and documented study opened up to me the world of Ivan Bilibin. An internet trawl of Abe Books showed (on that particular day) many reprints, but actual first editions of tales illustrated by Bilibin on offer from only two booksellers, Aleph-Bet Books in the USA and Politikens Antikvariat in Denmark.

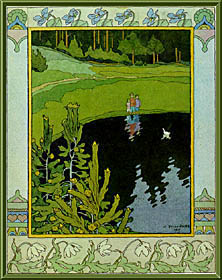

Bilibin’s book illustration is usually characterised by lively visual references to Russian history and folk art. As a graphic artist he had a pronounced ideology regarding the powerful line. The tones he favoured in his illustrations of Russian fairy and traditional tales hint at the bright and glorious, yet they are strangely muted; even in open vistas, the light might be have been filtered through a thick  forest canopy. Although in many of the scenes there is movement – often fast, excited, and possibly violent – it’s as if that movement has just become frozen, like a princess turned to stone or some such fairy-tale motif. There is a strangely ‘once-removed’ feel to his ornate images which, when it works, perfectly captures the dream-like quality of much of his subject matter, as in his illustrations for the Russian fairy-tale, The Little White Duck:a maiden gazes out to sea from a high tower, where, in the distance, beyond a tumble of turrets and onion domes, a fleet of boats leaves harbour to meet an unknown adventure – the whole image firmly trapped within an ornate border in shades of violet, olive green and yellow; or, three children at the edge of a lake watching as the little white duck glides inquisitively towards them, an innocent scene from childhood everywhere, here rendered brooding and dark, partly through the colour composition; a border shows snowdrops and violets, with other decorative elements drawn from traditional folk art. Those of Bilibin’s illustrations that appeal to me most are hauntingly memorable, very much part of the warp and weft of fairy-tale lore. But some of his illustrations seem over-fussy and, whatever the suggestion of movement, clumsily frozen. Sergei Golynets’ account of Bilibin’s life and work was most illuminating, providing me with a vocabulary with which to analyse my responses and enabling me to set the work in context.

forest canopy. Although in many of the scenes there is movement – often fast, excited, and possibly violent – it’s as if that movement has just become frozen, like a princess turned to stone or some such fairy-tale motif. There is a strangely ‘once-removed’ feel to his ornate images which, when it works, perfectly captures the dream-like quality of much of his subject matter, as in his illustrations for the Russian fairy-tale, The Little White Duck:a maiden gazes out to sea from a high tower, where, in the distance, beyond a tumble of turrets and onion domes, a fleet of boats leaves harbour to meet an unknown adventure – the whole image firmly trapped within an ornate border in shades of violet, olive green and yellow; or, three children at the edge of a lake watching as the little white duck glides inquisitively towards them, an innocent scene from childhood everywhere, here rendered brooding and dark, partly through the colour composition; a border shows snowdrops and violets, with other decorative elements drawn from traditional folk art. Those of Bilibin’s illustrations that appeal to me most are hauntingly memorable, very much part of the warp and weft of fairy-tale lore. But some of his illustrations seem over-fussy and, whatever the suggestion of movement, clumsily frozen. Sergei Golynets’ account of Bilibin’s life and work was most illuminating, providing me with a vocabulary with which to analyse my responses and enabling me to set the work in context.

Ivan Bilibin was born on 4 August, 1876, in Tarkhova, not far from St Petersburg. As a youngster he was always drawing; at the age of nineteen he enrolled at the School of the Society for the Advancement of the Arts and studied there till 1898. That summer he went to Munich and worked in a private art studio, an experience that opened up his sense of possibility in a most stimulating way. Gloom descended on his return home, but his sense of frustration was eliminated by the discovery of a similar studio set-up in St Petersburg, presided over by Ilya Repin. Bilibin revered Repin as an artist and teacher who ‘thought and taught in forms and line as simply as we think and talk to each other in words’, as he wrote in his 1930 ‘In Memory of Repin’.

Bilibin’s first of many commissions for illustration for magazines and journals came in 1899, from the World of Art, a journal produced by a circle of artists among whom Leon Bakst and Serge Diaghilev were leading lights; as well as producing the journal, the group mounted exhibitions to showcase the work of their members. This was the start of his professional career as an applied graphic artist. The following year ten of his illustrations for fairy-tales were included in the Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) exhibition. He had also pursued professional qualifications as a lawyer and in 1900 received a diploma – but he was frank with his family that his professional identity could be nothing other than as an artist, an assertion backed up by the fact that book and journal illustration was already coming in and he was beginning to make a name for himself in his chosen field. An important commission at this time came from the Department of State Documents which, between 1901 and 1903, published a series of Russian fairy-tales in six slim large-format paperbacks illustrated by Bilibin and also commissioned number of illustrations which were archived, but not published. By the summer of 1904 he had completed a series of illustrations for the bylina of Volgá and the department commissioned him to do more work, illustrating fairy-tales by Pushkin. He had also begun to make his mark in another sphere of graphic art:he designed the stage-set and costumes for a production of Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera Snow Maiden which opened in Prague in 1905.

Various Russian tradition arts, from pokerwork to architecture, are evident influences in Bilibin’s illustration. In an article on the ‘Folk Arts and Crafts in the North of Russia’, published in the World of Art in 1904, he rhapsodised about traditional Russian wooden architecture:’The main principle… is that the detail should never drown the whole. … The decoration is only pronounced in places, like a vignette at the end of the text’. Ironically, this description would not apply to much of his earlier work, where there is often such a clutter of detail that, if it doesn’t ‘drown the whole’, acts as visual white sound. As Sergei Golynets put it, Bilibin’s early illustration work is ‘overloaded with decorative motifs … the intricate frames around the illustrations, imitating poker work or wood carving, isolate them and detract from the unity of the page’. But his illustrations for The Little White Duck showed ‘growing professionalism. The little details which formed a precise rhythmical pattern do not destroy the unity of the whole. The lines acquire beauty and expressiveness, organising the composition’.

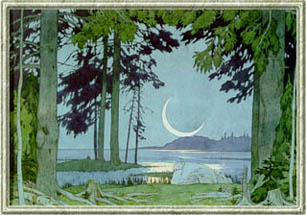

A stage set designed by Bilibin.

A stage set designed by Bilibin.

Bilibin was becoming increasingly successful in integrating image and decoration with the general design of the book and he became a leading exponent of this approach. Golynets points out that in this, he was very much part of the Art Nouveau movement which was sweeping Europe:’The idea that graphic design should be looked upon as the decoration of the book page, similar to linear ornament and silhouette, is in fact fundamental to the Art Nouveau movement’. Golynets goes on to cite a number of artists who were exponents of this style, including William Morris, Walter Crane and Aubrey Beardsley. Bilibin and his group ‘were even more consistent than their foreign counterparts in opposing book illustration to line drawing and tonal illustration.’

Bilibin identified his artistic roots in Renaissance woodcuts and Japanese art as well as ‘the art of Old Russia’. As an illustrator, he always bore in mind the end result, the printing process, how truly the paper to be used for the book would receive the image. His striking and humorous illustrations for Pushkin’s Tale of Tsar Saltan and Tale of the Golden Cockerel exemplify his integrated approach; sadly, he didn’t complete a series of illustrations for Pushkin’s Tale of the Fishermen and the Fish, which, like several other sequences he started, was not published.

Bilibin was influential in the development of the art of the illustrated book in twentieth-century Russia; ‘Bilibin is the first draughtsman to turn to Old Russian art in search of new motifs and new methods

… his attitude to the book art

… has in a certain sense changed the very nature of graphic art’, commented N. Radlov in Modern Russian Graphic Art (1917).

In 1920 Bilibin went to stay in Egypt, hungry for a new, ‘exotic’ environment. For most of his time there he stayed in Cairo, specialising in thr Byzantine-style art that was in demand by the Greek colony for icons and frescoes. He found himself enraptured by the architecture of mosques and their ‘head-spinning ornamentation’. In 1923 he married fellow artist Alexandra Shchekatikhina-Pototskaya; her work was to be displayed in the World Exhibition that year and the couple moved to live in Paris. They were based there, making forays to various parts of Europe, until 1936 when they returned to Russia. Throughout his life, Bilibin continued to work at book illustration, and take commissions for stage and costume design, particularly for opera. Back in Russia, he applied his artistic energies as vigorously as ever. He died in Leningrad in 1942 during the Second World War German blockade of the city.

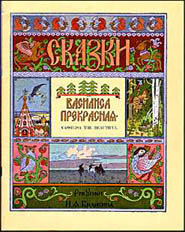

A Russian folk-tale illustrated by Bilibin.

A Russian folk-tale illustrated by Bilibin.

Copyright Jennie Renton 2005.

Comments