By

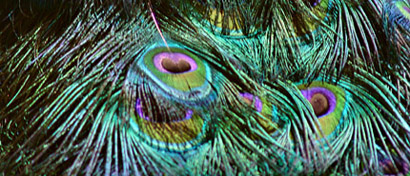

Peacock Feathers

Children waved. They carried strings of brown beads made from seeds. They waved the necklaces at the white people in the car. A few hundred yards on the English couple stopped so she could take pictures of the dam. They walked on bare granite koppies - a landscape of beached whales frozen in stone. The children had run hard to reach them. They gathered around the couple, holding up the strings of beads.

Children waved. They carried strings of brown beads made from seeds. They waved the necklaces at the white people in the car. A few hundred yards on the English couple stopped so she could take pictures of the dam. They walked on bare granite koppies - a landscape of beached whales frozen in stone. The children had run hard to reach them. They gathered around the couple, holding up the strings of beads.

‘No thank you, we don’t want any necklaces,’ said the woman. She smiled at them and continued taking pictures.

‘What is your home?’ one boy of about twelve years asked.

‘Oh no, let’s go back to the car,’ said the man.

‘I want to talk to them,’ she said. And to the children – ‘We are from England.’

The boys, they were all boys, smiled shyly.

‘What is your name?’ she asked the smallest boy. He looked frightened.

‘He is William.’

‘I am Lenin,’ the biggest boy said. He was a youth, strong and smiling.

‘Lenin? There’s a good name,’ she said.

‘Do you have pens?’ said another boy, suddenly brave.

‘Oh dear, I don’t think we have any. Let’s have a look.’ They had walked back with the children to the car. Her husband had got in the driver’s seat. She was in the passenger seat with the door open. The boys were standing next to her. She looked in her large leather bag. There was only her favourite pen. There was an A4 notebook.

‘Would you like some note paper?’

‘Yes, please, Madame.’

She tore pages from it and gave them to the boys. They grabbed them gratefully.

‘What have we got to give them?’ she asked.

‘Give them the water.’

They had an empty plastic bottle of mineral water and a nearly full bottle. Bottles were good collateral. They could be sold or bartered or their mothers could use them for filling at the well. What else to give them? They had come from their hotel with only enough to get them through the day. They gave them two small cans of Coke.

‘Do you have T-shirts?’ one asked. All the boys wore ragged but clean vests or shirts and shorts and no shoes.

‘No, only what we are wearing,’ she laughed. They were more relaxed now.

‘Do you go to school?’

Yes, they all went to school. They explained that they had to pay for their schooling – ten pounds a year. It was more than their parents could manage. The boys had to make money by making and selling seed necklaces to tourists to buy uniforms, books, paper and pencils.

‘What are you going to do when you finish school?’

‘I am going to be a teacher.’

‘I want to be doctor,’ the most shy boy admitted.

‘I want to be pilot,’ the outgoing child was definite.

‘I want to be a lorry driver,’ said the youth, solemn now. His earlier smile had made him look so much younger.

‘You all speak very good English,’ she said and they smiled happily.

‘May I take a photograph of you, please?’ she asked.

The youth and the children stood stiffly in a straggly line under the shade of an acacia.

She took several pictures, one for each of them and one for herself.

‘Please send me a photograph,’ said one.

They all gave their names and addresses to her and she wrote them with her best pen in her A4 notebook. ‘I will send you each a picture of yourself,’ she promised. ‘We don’t want to buy your beads. Save them for another buyer.’

The boys were pressing closely in at her door of the car. Only the youth stood back, his face unreadable.

Her husband had found all the coins they had and shared them among the waiting, open hands. The boys stood waving under the shade of the acacia tree as they drove away.

The lake now had a Zimbabwean name but people still used the old colonial English name – Lake Kyle. They drove off the road onto a dirt track looking for a hotel that had been sign-posted so they could have a drink and maybe some lunch. They had given the boys all their liquids. There were small blue-grey hills, lush vegetation and much agricultural activity all around – fields of high maize, round huts with makuti roofs, painted designs on the mud walls. Goats and chickens roamed. In the granite outcrops where fresh water pools gathered, children played and splashed. A beautiful naked girl bathed among them. She was about fourteen, small new breasts high on her rib cage, with long straight limbs, brown as treacle. Her wet hair was in tiny plaits tight to her round head, a huge smile splitting her face in half. She jumped up and down in the stream waving with the children at the couple in the car. Her pointed breasts jiggled. Her body glistened and gleamed. Some of the children ran towards the vehicle but it did not stop.

All along, children waved and laughed and women waved too, looking up from the pumping of water at a well, or digging in a field, to smile and wave. The men only frowned.

After an hour of driving along the tortuous track the English couple gave up the search for the elusive hotel and turned around and drove back to the main road and to the hotel where they were staying.

The dining room was gloomy in an old white colonial Africa way. Like a Cotswold cottage, thatched roof, tiny leaded windows, chintz curtains. There were even foxhunting prints on the walls. The heat and light of Africa kept out by glum imported Englishness. You had to eat your meals there. The outside seating was for drinks only, or bar snacks. The staff, dressed in immaculate white starched uniforms stood guard at the buffet, ladling out insipid hot food. The few guests ate quietly, whispering to each other. The gloomy atmosphere held them in its power. Laughter was not suitable here. Instead were the ghosts of white men, bosses, sternly looking over the shoulders of guests who had the audacity to be enjoying themselves.

Outside, at the entrance to the dining room, was the huge fan of a royal palm full of weaverbird nests. The yellow birds flitted in and out in an orgy of twittering and building. The nests were in various stages of construction or deconstruction. The birds pulled apart old disused nests in order to make room for a new home. They wove thin strips of shredded palm leaves into a hanging ball like a Christmas tree decoration. It was something for the guests to watch who were drinking outside in the shade of the jacarandas. You could tell the new nests by their bright green colour. The older nests were a browny yellow.

The couple had arrived the day before, and were to spend three nights there, before continuing their journey around Zimbabwe. They went to the tour office to book a tour but there was a notice to say that the guide was on holiday. Great Zimbabwe was close by, and next morning they drove to it and walked around the high granite walls of the mysterious ancient city. The intricately built walls were woven close together in places and they pressed between them through a grassy maze, the sky paled to a thin thread far above. It was hot and humid on the fortified hill. They were the only visitors climbing in the heat of the day. Perspiration ran down between her breasts. They saw two heaps of spoor – dark, dry, on rocks. Baboons? Leopard?

They were nearly at the top when, in the absolute silence, a hawk dropped from the sky next to them in a dive to kill. The noise was like a firework, a rocket. A searing, screaming whoosh – the air torn and severed by the hawk’s streamlined shape, its wings folded. A shock of speed. They looked over the wall to the hundreds of feet beneath them but could not see the bird – only the barren rocks. Had it even happened? They did not know for sure that it had been a hawk. They only surmised. She rested on a granite step, the cool of stone wonderful on her thighs and he carried on. Her head pounded with the heat and exhaustion. No bird song. Huge boulders balanced on each other. The wind cooled her skin. Her sunglasses slid down her damp nose.

When they walked down from the fortifications they had a cold drink at the little outside café. They were the only visitors. A family of vervet monkeys were tipping up glasses from empty tables, and looking into empty coke cans. Babies hung under the mothers’ bellies.

The couple drove back to the hotel and had a swim in the small pool where huge drowned maiden-flies floated and bumped into them. She rescued a frog that had jumped in and could not get out. A gardener, his mauve-plum skin glistening with perspiration, slowly swept leaves from the coarse grass. Thunder rolled in the lowering sky. A half-built thatched hut seemed to have been abandoned by the builders. A sheet of corrugated iron had blown onto the grass and wire tangled it. Perhaps it was to have been a poolside bar.

She showered and dressed, tugging at a dress zip. Her breasts had grown big, since she had started on the hormone replacement therapy, after her operation, and she could not get used to the idea of being fleshy and voluptuous. She had always been slim and tall and clothes had always hung well on her. Now she did not know what to wear and the heat bothered her and made her fractious. She chose a long, creased, (they had no iron) brown linen dress that skimmed her hips and flattened her breasts. Her belly felt bloated.

They sat under the cool dense branches of the jacarandas and she had a whiskey with ice and he had a beer. At another table sat two black women with a small girl of about four years old. They were drinking Coke and chatting quietly. The child stared at the white couple.

The leafy green jacarandas had none of the glamour of the flowering season, when purple blue blooms would shroud the scene in a blue hazy mist and later petals would shower like confetti on the people below.

Suddenly, from out of the dark branches floated a peacock feather. It drifted down onto the English couple’s table.

‘Oh! Look! How wonderful!’ the English woman cried. He glanced at it briefly and smiled slightly and went back to reading his book. She examined the gleaming blue green feather, the glistening eye gold and blue and green. She looked up but could not see a bird. Another feather floated down, nearby, and then another. She gathered five feathers in all. Three were tail feathers – with the astonishing miraculous eye at the end – and the others were shorter, just as beautiful. She was in an ecstasy of delight over them. Magic! That they had fallen into her lap, practically! He smiled indulgently and carried on reading his book.

She placed four of the feathers on the table and got up and walked towards the Zimbabwean women and child. The child saw her and froze in a horror of expectation and dismay. The white woman smiled at the little girl and held out a feather with an eye. The child cringed in her chair, grimacing and turning away her small head. Her mother laughed and took the feather and smiled.

The English woman went back to her table and ordered another whiskey. She read her book. A little while later she looked up and saw the child smiling, laughing, twirling the long peacock feather in her hands, throwing it up and watching it flutter down. The little girl smiled shyly at the white woman.

The next morning the English woman saw that the cleaner’s trolley, which had on it piles of clean towels and sheets, had several peacock feathers tucked in at the end. She asked the cleaner about the feathers. He said that there had been seven peacocks at the hotel but guests had complained of the noise. The owners had got rid of six of the birds to other hotels. Now there was only one. She imagined the poor silent creature sitting high in the jacaranda, moping and lonely for its kind, and slowly, surely, losing its beauty.

Ann Kelley is a photographer and prize-winning poet who once nearly played cricket for Cornwall. She has published a collection of poems and photographs, a book of photos of St Ives families and an audio book of cat stories.

Ann Kelley is a photographer and prize-winning poet who once nearly played cricket for Cornwall. She has published a collection of poems and photographs, a book of photos of St Ives families and an audio book of cat stories.

She lives with her second husband and several cats on the edge of a cliff in Cornwall where they have survived a flood, a landslip, a lightning strike and the roof blowing off. She runs courses for aspiring poets at her home, writing courses for medics and medical students, and speaks about her poetry therapy work with patients at medical conferences.

She is the author of The Burying Beetle, a novel about a young girl, Gussie, with a life threatening heart condition, who moves with her mother from the chaos of London to the natural splendour of the Cornish coast. Gussie reads about the burying beetle, an unusual creature which has the curious habit of burying dead birds and mice, and determines to see one before she dies. (Luath Press, ISBN 1842820990 £9.99 PBK).

She is the author of The Burying Beetle, a novel about a young girl, Gussie, with a life threatening heart condition, who moves with her mother from the chaos of London to the natural splendour of the Cornish coast. Gussie reads about the burying beetle, an unusual creature which has the curious habit of burying dead birds and mice, and determines to see one before she dies. (Luath Press, ISBN 1842820990 £9.99 PBK).

Article © Ann Kelley 2005, Black and White Peacock Photograph © Ann Kelley. Author Portrait © Ron Sutherland. The colour images are courtesy of Lauren Rosenbaum and Katmystiry, at morguefile.com.

Comments