By

Through a Glass Lightly

Annie Helen Nairn Monro was born on 16th December 1901, in Calcutta, where her father David L Monro was working as a newspaper editor. She came to Edinburgh as a child and was educated at George Watson’s Ladies College, leaving in the session 1917-18, due to ill health. After taking an Arts degree at Edinburgh University she proceeded to Edinburgh College of Art, where she specialized in wood engraving, receiving her Diploma in 1927.

Annie Helen Nairn Monro was born on 16th December 1901, in Calcutta, where her father David L Monro was working as a newspaper editor. She came to Edinburgh as a child and was educated at George Watson’s Ladies College, leaving in the session 1917-18, due to ill health. After taking an Arts degree at Edinburgh University she proceeded to Edinburgh College of Art, where she specialized in wood engraving, receiving her Diploma in 1927.

While still at college, she had visited the Edinburgh and Leith Flint Glass Works and submitted designs for glass to the company: these included traditional intaglio work as well as more modern designs for candlesticks and light fittings. Several still survive with comments such as This cannot be done. It has never been done before…This is too new, too familiar. It will not sell. As she wrote later, it was frustrating at the time. Her frustration was no doubt increased in 1930 when one of her designs was commended in the Royal Society of Arts Design Competition and when, in 1935, the company included examples of her work, along with that of five other graduates, in the Royal Academy of Arts Survey of British Industrial Art, which showcased the best of contemporary design.

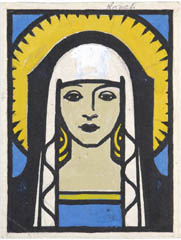

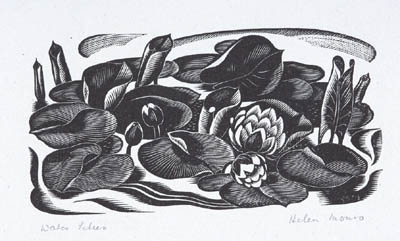

The quality of her engraving and imaginative use of the medium was better appreciated by the publishing industry, particularly the Edinburgh publisher Thomas Nelson and Sons. For forty years, from 1933, she illustrated a wide range of educational and recreational books for children for Nelson, as well as producing illustrations and covers for other publishers.

Some striking art deco designs had been used by the Edinburgh and Leith Flint Glass Works for publicity material – price lists and adverts, but her first major commissions as an illustrator were for the Nelson Classics editions of Alice in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking-Glass. This must have been a daunting challenge for a young designer haunted, no doubt, by the ghost of Tenniel. Bravely, she made Alice a typical 1930′s child with bobbed hair, a knee-length dress, long white socks and black shoes, revitalising the whole story. For the same publisher she varied her style to suit the subject matter in commissions for editions of George Dasent’s Tales from the Norse, Charles Kingsley’s The Heroes, and Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo.

When asked to illustrate two volumes of A.R.B. Haldane’s accounts of his experiences as a fisherman, The Path by the Water, she was able to show her love of the countryside in general and plants in particular. Her precision of observation and superlative draughtmanship were both brilliantly displayed, to be repeated in Thomas Hamilton’s Forest Trees. Among her finest achievements were the illustrations for the 1948 edition of Michael Fairless’s The Roadmender – an uplifting bestseller, first published in 1902. The mood of the story is captured in every illustration – all clearly based on a close reading of the text.

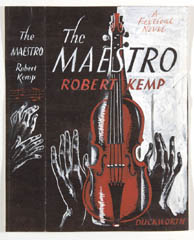

Attention to the detail of the text, as well as her sense of humour is also demonstrated in her jacket designs for Robert Kemp’s whimsical novel The Malacca Cane and his satirical account of the Edinburgh Festival, The Maestro.

When, in 1938, the College of Art elected her to an Andrew Grant Fellowship, her interest in glass had not diminished and, on the advice of Prof W.E.S. Turner, Head of the Department of Glass Technology at Sheffield University, she decided to study at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Stuttgart under Professor Wilhelm von Eiff. There followed two years of intense study of glass making and decorating techniques. Her diary of this period shows how she was fired with enthusiasm for the medium. With typical understatement she records, on 14 August 1939, just when term ended at Stuttgart it seemed advisable to be on the other side of the frontier, and I left Stuttgart for Zurich. She took with her only some photographs of work she had done and a sand-blasted and wheel engraved glass for her father (cat.no. 216). She spent the following months in the UK visiting glass collections, factories, designers, and establishing a small studio in Sheffield and also one in Edinburgh at 50 Queen Street. In October 1940 her fellowship was renewed and she was asked to establish a department of glass engraving at the College, which started in January 1941 with four students, and two lathes. Her experience in Europe and England had convinced her that the department should not be limited to just one aspect of the art of glass but should cover all aspects of glass design. For the next thirty years, she would pursue three careers, as a graphic artist, as a glass engraver and as a teacher.

Despite this extraordinary work-load, she was still able to find time for two visits to Hadelands in Norway to instruct trainee engravers and so help in the reconstruction of the glass industry, which had been virtually destroyed during the German occupation.

She married Professor Turner in 1943 and in future used the name Helen Monro Turner.

At the college she was appointed a full-time instructor in 1947 and the Department expanded. Lampworking was added, then sand-blasting, cutting wheels and finally a furnace and a glass-maker added to the staff. In much of this development, she was assisted by a former student John Lawrie who also helped in establishing her own studio at Juniper Green in 1956.

Her reputation as a glass engraver spread rapidly and there were constant demands for items for presentations, anniversaries etc, leaving little time for speculative work or exhibitions resulting in relatively few items being found in public collections. The scale of her work ranged from a single glass or a tiny engraved crystal box to huge architectural commissions such as the windows on the staircase in the National Library of Scotland. For each there would be a period of research before precise and detailed designs were produced – in themselves consummate works of art.

From the department at the College of Art came a stream of glass artists who transformed the glass industry in post-war Scotland. Her declared aim, as a teacher, had been to communicate enthusiasm…the best work is done con amore… the final principle into which all other rules resolve themselves is quite literally love of the work, an act of devotion, a practice of the art of giving, which is indeed the first principle of the art of living.

Helen Monro Turner was modest and self-effacing; essentially shy but also extremely determined. She accepted only the best from herself, and consequently from others. She left an artistic legacy both in her own work as an illustrator and engraver, and in the way she had encouraged her students to set themselves the highest standards and to question, to challenge, and to experiment.

Helen Monro Turner was modest and self-effacing; essentially shy but also extremely determined. She accepted only the best from herself, and consequently from others. She left an artistic legacy both in her own work as an illustrator and engraver, and in the way she had encouraged her students to set themselves the highest standards and to question, to challenge, and to experiment.

Brian Blench gratefully acknowledges receipt of a grant from the Sandeman award fund of Strathmartine Trust.

© Brian Blench, June 2007

The Helen Munro Turner Memorial Exhibition at The Scottish Gallery, 16 Dundas Street, Edinburgh, EH3 6HZ, runs from 7th to 28th July.

T. 0131-558 1200

Comments