By

Darien to Dream

Before I began to write my novel, I spent a lot of time in libraries. Reading is the fuel that drives writing for me. And I soon found that from when the Company of Scotland was created in 1695, through the planning, implementation and failure of its attempt to establish a colony at Darien, to its demise in 1707, there was generated an abundance of government and business documents, pamphlets, letters, ballads and polemics. One of my favourite contemporary pamphlets is the Rev. Francis Borland’s The History of Darien. Some of the ballads were collected by David Laing in Various Pieces of Fugitive Scottish Poetry in 1853. There is also Lionel Wafer’s A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, originally written c.1695, published by the Hakluyt Society in 1934. Wafer, a buccaneer surgeon, lived with the Cuna Indians in Darien for several months, and was consulted by the directors of the Company when they were planning their expedition. In 1849 the Bannatyne Club published a selection of documents and letters, The Darien Papers. George Pratt Insch published Darien Shipping Papers in 1924. The most accessible account today is John Prebble’s The Darien Disaster.

Before I began to write my novel, I spent a lot of time in libraries. Reading is the fuel that drives writing for me. And I soon found that from when the Company of Scotland was created in 1695, through the planning, implementation and failure of its attempt to establish a colony at Darien, to its demise in 1707, there was generated an abundance of government and business documents, pamphlets, letters, ballads and polemics. One of my favourite contemporary pamphlets is the Rev. Francis Borland’s The History of Darien. Some of the ballads were collected by David Laing in Various Pieces of Fugitive Scottish Poetry in 1853. There is also Lionel Wafer’s A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, originally written c.1695, published by the Hakluyt Society in 1934. Wafer, a buccaneer surgeon, lived with the Cuna Indians in Darien for several months, and was consulted by the directors of the Company when they were planning their expedition. In 1849 the Bannatyne Club published a selection of documents and letters, The Darien Papers. George Pratt Insch published Darien Shipping Papers in 1924. The most accessible account today is John Prebble’s The Darien Disaster.

The main character in my novel is a time traveller from the present day who becomes an apprentice surgeon. I was brought up on swashbuckling movies where ship medicine begins after the swordplay, involves rum and carpentry, and ends with the pegleg and parrot. In The Fundamentals of New Caledonia I present a more accurate viewpoint.

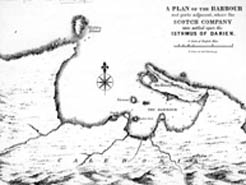

Right: Map of the Isthmus of Darien, Bannatyne Club, 1849. Above: Leith Harbour c. 1700.

Right: Map of the Isthmus of Darien, Bannatyne Club, 1849. Above: Leith Harbour c. 1700.

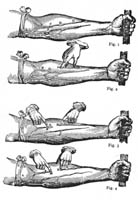

The foremost medical texts that would have been available at that time were Friedrich Hoffman’s Fundamenta Medicinae, which is a general system of medicine, and William Harvey’s The Circulation of the Blood, which is a classic scientific thesis. Harvey demonstrated that in all animals blood is pumped from the heart, circulates around the body and returns to the heart. Surgeons such as Archibald Pitcairn accepted his theory as proven, though it was long before microscopes were sophisticated enough to allow observation of the capillaries that make this circulation possible.

Apart from Pitcairn’s writings on medicine, I came across an edition of his play, The Assembly, which is a satire on the Church of Scotland and Edinburgh society at the beginning of Hanoverian rule. Along with the revenge tragedies such as Thomas Otway’s Venice Preserved, this formed the basis for part of my novel. The late seventeenth century was not a good time for theatre in Scotland, nor for literature generally. This was the generation before Alan Ramsay’s revival of the vernacular in The Gentle Shepherd. Yet people were writing in Scots. In personal letters and journals, even in receipts and accounts, Scots words were employed in the service of the Company. These indicate that written language was rather fluid in its appearance. And a reading of such a document as the instructions for building one of the Company ships would bear this out:

Eight good breast hooks afore under the deck wth a good stop for the fore-mast and of each side Twelve good Topp Ryders and one Standert. The ship to be plankt from ye keill to the loyer waill wth good 4 In:plank and each skairfe 4 ft long. The Round house soe long as Convenient and to be Layed with 2 In:Spruice dealls. A head wth Reilles and all things belonging to itt wth beatts and Catt heads and athings usefull for such a ship… ane open Gallery beheft with a Rither and Tillow and the Stairn well Secured…The builkhead of the Cabine wth 2 upright standards and Threshould… The Ship to be calk’d Twice wth outt and once wth in… and to be well Treenaill’d as is usewall in ye Staitts ships wth dry Treenaills… Two barths, a Stewart Room and a well for the pump and a powder Room.

This gunpowder room is described in Scots that is a far cry from the literary Scots used by the makars. Robert Sempill, writing a century before, showed the strong relationship between shipmaster and ship, in ‘The Ballat maid upoun Margret Fleming’:

I haif a littill Fleming berge,

Off clenkett work bot scho is wicht;

Quhat pylett takis my schip in chairge

Mon hald hir clynlie, trym and ticht,

Se that hir hatchis be handlit richt

With steirburd, baburd, luf and lie,

Scho will sale all the winter nicht

And nevir tak a telyevie.

Right: Figure from Harvey’s The Circulation of the Blood.

Right: Figure from Harvey’s The Circulation of the Blood.

Although the literary light of the makars had dimmed, it is not hard to find more extended pieces of Scots prose from the seventeeth century. There is John Nicoll’s A Diary of Public Transactions etc, published by the Bannatyne Club in 1836, and amongst the Maitland Club’s Caldwell Papers (1854) are accounts such as the Tour of William Mure of Glanderstone in the year 1696. I wrote my novel in a language that seems to rest on uncertain ground, that flows according to different influences of style, register and time. This reflects the position of Scots as a language, just as it reflects the experience of the Darien settlers trying to build a new world on very shoogly foundations.

Extract from New Caledonia

Presently wee drappt anchor in the lee o Golden Island that lyes ae league aff the Darien main. Captain Pennecuik wald claim the coast for King William and the Company. He floated Saint Andrew’s pinnace, trimming her aneath lateen sails, and mounting a culverine in her bough. He stude in her stern, wi his perspective glass in haund, a fine gilt sword in the scabbard att his thigh, ane reid pennant fluttering on the foremast, and a saltire on the main. The Company’s rising sun flew att her prow. Now the Commodore wes rady tae be first ashoar. But some Indians had seen our fleet lying aff, and foregatherit on the beach. Aweir than o running his pinnace up on the sand, he tuk ae glisk through his glass, and seeing they are aa dresst in warriour array, sent a young seaman’s lad sooming.

Presently wee drappt anchor in the lee o Golden Island that lyes ae league aff the Darien main. Captain Pennecuik wald claim the coast for King William and the Company. He floated Saint Andrew’s pinnace, trimming her aneath lateen sails, and mounting a culverine in her bough. He stude in her stern, wi his perspective glass in haund, a fine gilt sword in the scabbard att his thigh, ane reid pennant fluttering on the foremast, and a saltire on the main. The Company’s rising sun flew att her prow. Now the Commodore wes rady tae be first ashoar. But some Indians had seen our fleet lying aff, and foregatherit on the beach. Aweir than o running his pinnace up on the sand, he tuk ae glisk through his glass, and seeing they are aa dresst in warriour array, sent a young seaman’s lad sooming.

He’s afeart they might be cannibals.

Comments