Tracking Tranter

There is no doubt that in his lifetime Nigel Tranter established himself as one of the most warmly regarded Scottish writers. This is reflected in the number of websites and chat groups dedicated to  him, including www.nigeltranter.co.uk, where collectors are offered a book search service. Some Tranter titles are fetching pretty high prices these days. According to Colin Mills, compiler of The Tranter Bibliography, the first edition of Columba (1987) goes for about £200, and Cable from Kabul (1967) has exchanged hands for as much as £600. Perhaps symptomatic of Tranter’s spectacular mass-market popularity and the fact that his books were read to bits, his first editions tend to surface bereft of dustwrappers. It is a particularly useful feature of Mills’ book, launched in Wigtown Book Town last spring, that it contains 293 full colour reproductions of wrappers and covers.

him, including www.nigeltranter.co.uk, where collectors are offered a book search service. Some Tranter titles are fetching pretty high prices these days. According to Colin Mills, compiler of The Tranter Bibliography, the first edition of Columba (1987) goes for about £200, and Cable from Kabul (1967) has exchanged hands for as much as £600. Perhaps symptomatic of Tranter’s spectacular mass-market popularity and the fact that his books were read to bits, his first editions tend to surface bereft of dustwrappers. It is a particularly useful feature of Mills’ book, launched in Wigtown Book Town last spring, that it contains 293 full colour reproductions of wrappers and covers.

‘An absorbing story, blending adventure and romance, set in picturesque highland scenery’:Trespass, the first Tranter novel, summed up on the jacket blurb in words that could apply to any and all of the succession of novels that poured from his pen.

In the early Tranter novels, men well-endowed with pipes, trilbies and testosterone, lock antlers over territorial disputes. In Trespass, hero-holidaymaker David Scott ‘takes the law into his own hands’ over a boundary issue (Leylandii wars transposed to the Scottish Highlands.) In his second novel, Mammon’s Daughter, a Yorkshire millionaire estate owner is defied by Highland crofters, who, preferring ‘to continue in the ways of their forebears’, see off his latter-day ‘improvements’.

In the early Tranter novels, men well-endowed with pipes, trilbies and testosterone, lock antlers over territorial disputes. In Trespass, hero-holidaymaker David Scott ‘takes the law into his own hands’ over a boundary issue (Leylandii wars transposed to the Scottish Highlands.) In his second novel, Mammon’s Daughter, a Yorkshire millionaire estate owner is defied by Highland crofters, who, preferring ‘to continue in the ways of their forebears’, see off his latter-day ‘improvements’.

Nigel Tranter could spin a tale out of the air. In his third novel, Harsh Heritage, he is already turning to Scottish history to give a spine to his tales. ‘Could a curse dog successive generations of the Macarthy chiefs? Elspeth Macarthy, dying at the Clearances, said it would. Or would not a strain of insanity, imagination and coincidence, provide a more rational solution?’, the jacket blurb bizarrely demands. ‘Either way, or both, down the years the harsh heritage travels…’ We are now primed for the appearance of the strange wild daughter of the last of the Macarthy Neills and that other mandatory Tranter ingredient:destiny. That which has to be faced. That which must be obeyed, or rue the day.

It never takes long for Tranter’s heroes and heroines to strip down to their gender essentials. While he never actually says his heroes are hung like donkeys, it would be perverse to imagine them any other way (could it be that H. Rider Haggard and Edgar Rice Burroughs were seminal influences?)

Noble yet brutal men of lineage and spirited yet yielding damsels populate Tranter’s world. Scratch even the modern coquette and you will find the comely mediaeval wench.

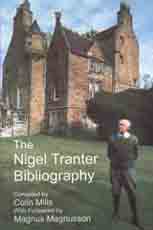

This Tranter reverie has been inspired by a new book based on the extensive collection assembled by Colin Mills, a Northumberland architect who now lives on the Island of Arran. For Mills, Tranter brings Scottish history alive. He is the fire in the literaplainplainry heather. Previously a keen stamp collector, he began to assemble Tranter books.

‘Searching for Nigel’s books in secondhand bookshops, I discovered titles that were of different appearance to those that I already owned, later editions, sometimes by different publishers. I had to buy!’

‘Searching for Nigel’s books in secondhand bookshops, I discovered titles that were of different appearance to those that I already owned, later editions, sometimes by different publishers. I had to buy!’

Nigel Tranter is mostly known for his Scottish historical novels but, as Mills points out, he turned his hand to a wide variety of themes, settings and subjects, both fiction and non-fiction.

‘Early in his writing career, which spanned sixty-five years, he wrote romantic adventure novels, mostly set in Scotland but occasionally venturing across the Border and overseas

… the Baltic, the Middle East, the Amazon, the Pyrenees. His twelve children’s adventure books are very elusive, even though I’ve scoured specialist children’s bookshops and catalogues for them. He also wrote a short story for the Collins Boys Annual for 1963.’

Tranter’s first book, however, was non-fiction. ‘Fortalices and Early Mansions of Southern Scotland (The Moray Press, 1935) sprang from his great love for the smaller Scottish castles. He was responsible for the illustrations in the book, having a good eye and a well developed drawing ability – originally, he had wanted to become an architect. This book was the precursor to the five-volume edition (1962-70), which many consider to be the work for which he will be remembered.

Then, as an established author, Nigel wrote a number of travelogues, notably the four volumes (1971-77) of The Queen’s Scotland. The most difficult to find was volume four, Argyll and Bute, which includes Arran.’

Mills has done his fellow Tranter enthusiasts a real service in compiling images of so many of the books, and fellow collectors will doubtless forgive some of the vagaries of presentation. Unfortunately the title The Nigel Tranter Bibliography may suggest something altogether more detailed.

Mills has done his fellow Tranter enthusiasts a real service in compiling images of so many of the books, and fellow collectors will doubtless forgive some of the vagaries of presentation. Unfortunately the title The Nigel Tranter Bibliography may suggest something altogether more detailed.

Mills presents a check-list of c. 137 titles, with dates of publication and basic bibliographic data. As a collector, he has dedicated considerable energy to accumulating Tranter’s books, complete with dustwrappers. Until very recently it was commonplace for libraries, including the National Library of Scotland, to discard dustwrappers – something which seems almost sacrilegious in this visually attuned, marketing-oriented age. The succession of Tranter dustwrappers displayed gives a graphic representation of the marketing of this highly successful author. For novels with Highland settings, a sentimental smorgasbord of mountains, maidens and warriors; there are flags and broadswords and fine Arab mares, presented in a coy iconography that would not insult the proprieties of the most respectable bookshelf – sex, death, power and blood are tacitly promised. With few exceptions, these images do not reflect the apparent changes in public taste between 1937 and the present day. They signal escape into a lost world where destiny is never more than a hoof-beat away.

The jacket for The Chosen Course (1949), designed by Sax, shows a tweedy man and a woman gazing up at him (secretary-chic in neat pink blouse and tight black skirt, although they are apparently climbing a mountain). They play out the intense drama suggested by their body language exactly as the blurb states:’against the exciting background of the great hills.’ Apart from the unlikely blouse, the colours are gentle, sunset hues, greys, browns and blues. However, for the 1980 Molendinar Press edition, designer Jim Hutcheson took Sax’s original image, tweaked the perspective, altered the colour composition to ochre and earth tones. The greatest range of images for one title appears to be for The Stone. The first edition wrapper, one of many designed for Tranter novels by Val Biro, is a humorous melange of cameos and characters from this tale of a plot to steal the Stone of Destiny and return it to Scotland. The book was published not long before the actual attempt. The 1959 US edition, on the other hand, uses bold typography and a frivolous, loud ‘tartan’ block; the shout line proclaims, ‘A madly funny novel of what happens when the English and the Scots start looking for the new stone of Scone.’ There is an altogether more portentous feel to the 1997 paperback reprint from B&W, showing a photograph of Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey, with the stone underneath; the cover blurb asks, ‘Is this the Stone that finally returned to Scotland in 1996…’

The jacket for The Chosen Course (1949), designed by Sax, shows a tweedy man and a woman gazing up at him (secretary-chic in neat pink blouse and tight black skirt, although they are apparently climbing a mountain). They play out the intense drama suggested by their body language exactly as the blurb states:’against the exciting background of the great hills.’ Apart from the unlikely blouse, the colours are gentle, sunset hues, greys, browns and blues. However, for the 1980 Molendinar Press edition, designer Jim Hutcheson took Sax’s original image, tweaked the perspective, altered the colour composition to ochre and earth tones. The greatest range of images for one title appears to be for The Stone. The first edition wrapper, one of many designed for Tranter novels by Val Biro, is a humorous melange of cameos and characters from this tale of a plot to steal the Stone of Destiny and return it to Scotland. The book was published not long before the actual attempt. The 1959 US edition, on the other hand, uses bold typography and a frivolous, loud ‘tartan’ block; the shout line proclaims, ‘A madly funny novel of what happens when the English and the Scots start looking for the new stone of Scone.’ There is an altogether more portentous feel to the 1997 paperback reprint from B&W, showing a photograph of Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey, with the stone underneath; the cover blurb asks, ‘Is this the Stone that finally returned to Scotland in 1996…’

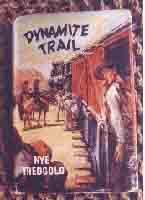

During the 1950s, those bleak post-war days when John Wayne stalked the big screen and every kid had a cowboy outfit, Ward Lock published eleven Westerns written by Tranter Nye Tredgold. Good guys and bad guys shoot it out and right wins the day in ‘breathless’ adventures like Dynamite Trail (1953) and Heartbreak Valley (1956).

During the 1950s, those bleak post-war days when John Wayne stalked the big screen and every kid had a cowboy outfit, Ward Lock published eleven Westerns written by Tranter Nye Tredgold. Good guys and bad guys shoot it out and right wins the day in ‘breathless’ adventures like Dynamite Trail (1953) and Heartbreak Valley (1956).

Eleven Nye Tredgolds were published in the 1950s as hardbacks priced at four to eight shillings, with paperback versions at 1s.6d. These are now rare.

‘One of the high spots of my experiences as a collector was one morning when I was phoned by a bookseller:’Colin, I have a chap standing here with a Nye Tredgold, with a dedication by the author. Are you interested?’ Was I!’ First edition Nye Tredgolds are exchanging hands in excess of £300. No collection can be complete without them – I have as yet to achieve that!’

One of his most exciting moments was finding an uncorrected proof copy of The Price of the King’s Peace in its publisher’s wrappers, and finding between its pages a letter dated January 1981 from the author to an admirer in South Devon:

I note that you are especially interested in Mary Queen of Scots, and suggest that I should write a novel about her. I have done, you know, although not in a very detailed fashion. I wrote one, long ago, called The Queen’s Grace (1953); and of course she also comes into The Master of Gray (1961). I have not done one of the big ones specifically about her, for I feel that poor Mary has been somewhat ‘over-exposed’ as they say, written about just too often, like Bonnie Prince Charlie. You see, there are so many other colourful and dramatic characters in Scotland’s long story who are never written about and therefore little known; and I have set myself the task, duty and pleasure of chronicling most of those. I have still quite a number to deal with. Perhaps when I have, if ever, got to the end of my list, I might make a belated stab at Mary again.

I note that you are especially interested in Mary Queen of Scots, and suggest that I should write a novel about her. I have done, you know, although not in a very detailed fashion. I wrote one, long ago, called The Queen’s Grace (1953); and of course she also comes into The Master of Gray (1961). I have not done one of the big ones specifically about her, for I feel that poor Mary has been somewhat ‘over-exposed’ as they say, written about just too often, like Bonnie Prince Charlie. You see, there are so many other colourful and dramatic characters in Scotland’s long story who are never written about and therefore little known; and I have set myself the task, duty and pleasure of chronicling most of those. I have still quite a number to deal with. Perhaps when I have, if ever, got to the end of my list, I might make a belated stab at Mary again.

Much to his regret, Colin Mills never had the opportunity to meet Nigel Tranter. The letter quoted above is one of his most treasured possessions.

‘I think it shows what a generous man he was towards his admirers. He eventually did write a ‘big one’ about Mary, but before that he wrote two further novels about people in her milieu – Warden of the Queen’s March, 1989 and The Marchman, 1997, bringing into the fabric of Scotland’s popular heritage figures who might otherwise have slipped into total obscurity. December 2004 is the scheduled date for Marie and Mary, the story of Mary and her mother, Marie of Guise.

‘I think it shows what a generous man he was towards his admirers. He eventually did write a ‘big one’ about Mary, but before that he wrote two further novels about people in her milieu – Warden of the Queen’s March, 1989 and The Marchman, 1997, bringing into the fabric of Scotland’s popular heritage figures who might otherwise have slipped into total obscurity. December 2004 is the scheduled date for Marie and Mary, the story of Mary and her mother, Marie of Guise.

‘Nigel Tranter was very self-effacing. He said he wrote ‘to pay the rent’. He never thought of himself as a great writer. He was certainly a great Scot.’

On a recent round of Edinburgh bookshops, Colin Mills showed me the latest addition to his collection – a paperback of There are Worse Jungles (a ‘desperate quest’ for a missing aircraft in the Amazonian jungle). He was wildly excited at his ‘find’, having just acquired it via the internet from Australia. His collector’s heart thrilled at the prospect of discovering further, as yet unidentified covers, which he will no doubt display in the next edition of The Tranter Bibliography.

On a recent round of Edinburgh bookshops, Colin Mills showed me the latest addition to his collection – a paperback of There are Worse Jungles (a ‘desperate quest’ for a missing aircraft in the Amazonian jungle). He was wildly excited at his ‘find’, having just acquired it via the internet from Australia. His collector’s heart thrilled at the prospect of discovering further, as yet unidentified covers, which he will no doubt display in the next edition of The Tranter Bibliography.

The Nigel Tranter Bibliography, compiled by Colin Mills, with a foreword by Magnus Magnusson, HB, £29.95 from Underhill Publications, Isle of Arran, KA27 8EW

Copyright Jennie Renton 2005.

Comments