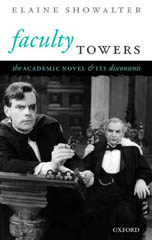

Faculty Towers

‘The academic novel,’ since its emergence in the 1950s, ‘has offered a full social history of the university, as well as a spiritual, political, and psychological guide to the profession. Each decade has foregrounded the scandal and the headlines of higher education – class, political infighting, feminism, sexual harassment, political correctness. How has it changed?’

‘The academic novel,’ since its emergence in the 1950s, ‘has offered a full social history of the university, as well as a spiritual, political, and psychological guide to the profession. Each decade has foregrounded the scandal and the headlines of higher education – class, political infighting, feminism, sexual harassment, political correctness. How has it changed?’

Having spent the greater part of her professional life working within universities, the American writer and critic Elaine Showalter is naturally very well placed to discuss the development of the academic novel, or from the US perspective, the ‘campus novel’. In this entertaining and very personal study, Showalter has concentrated on one aspect of the genre, namely the discontents who inhabit or haunt the fictional worlds of their creators. Not that she does a hatchet job on the writers, characters or universities under examination. When all is said and done, Showalter writes almost affectionately about them, despite the fact that she says ‘a disconcerting number of strange and unpleasant women in academic novels are named Elaine’; twice she has been translated into academic fiction herself, once as a ‘voluptuous, promiscuous, drug-addicted bohemian, once as a prudish dumpy, judgemental frump.’ She admits preferring having been cast as ‘the luscious Concorde grape’ to her role as ‘the withered prune’.

It was during her adolescence in the 1950s that Showalter became addicted to reading academic novels, then almost a new genre which had emerged from the post-war expansion in higher education on both sides of the Atlantic. Showalter argues that the genre emerged from the rich source material of the social or communal and institutional elements of university life and, thanks to the introduction of creative writing courses, from a professional writer or two thrown in ‘to observe the tribal rites of their colleagues from an insider’s perspective.’ As a creation story, this is quite credible, though the teaching of creative writing arrived later in UK universities than it did in those in the US.

‘Faculty Towers is not intended to be a comprehensive history of the Anglo-American academic novel over the past fifty years’, however, as a cultural historian, Showalter takes a chronological approach to her subject, identifying Trollope’s Barchester novels and Middlemarch as literary precursors of the genre. Thereafter, she romps through the years from 1949: the fifties and their ivory towers; the sixties and their tribal towers; the glass towers of the seventies; the feminist towers of the eighties; the tenured towers of the nineties and the tragic towers of the twenty first century. Almost all the usual suspects are here: Amis, Bradbury, Byatt, Cross/Heilbrun, Dobson, Hynes, Lodge, Lurie, Roth, Shields, and Snow. Roberston Davies is absent, as is our own Kate Atkinson, but Showalter does not claim to make this a comprehensive history, more of a personal reminiscence. And while it is a bit of a romp, it is largely a very enjoyable read.

Because Showalter is so close to the subject about which she writes, she can be very insightful about her quarry, often making cuttingly sharp observations about academics and academic life and very honest, personal observations that seem to be devoid of irony. She writes, ‘perhaps it’s the ultimate narcissism for an English professor to write literary criticism about novels by English professors about English professors.’ It probably is. Showalter is at her best when she writes about women and the academic novel, whether as novelists, professors, students, faculty wives, detectives or murder victims, and makes the point that even well into the sixties ‘women were still virtually unrepresented in academic fiction, except as murder-victims’, and that overall, in the sixties, ‘feminism took a long time to steep into the academic novel, even when women were writing it.’ In her chapter on the eighties and their feminist towers, Showalter reveals that it was only during this period that women begin to ‘appear in the academic novel as serious contenders for tenure, status, and all the glittering prizes.’ Later, as the genre further develops and changes, Showalter remarks, ‘indeed, women department chairs were marked out as murder-victims in many ’90s books, although tenured women who are found dead were viewed less as tragic martyrs than as job vacancies.’ Because of her closeness to her subject, Showalter can sometimes be disappointing, particularly when in the place of analysis or commentary she prefers to give a plot summary of some of the novels – but even when she does this, one is reminded about what great fun these novels were to read first time round, and how satirical they remain.

Having surveyed the academic novel of the previous five decades, Showalter brings us bang up to date: the idyllic, reverent, utopian pre-war world of C.P. Snow’s Cambridge, when not utterly pulled down and destroyed, has been replaced by universities with ‘extraordinarily high homicide-rates, the most sexually predatory and unprincipled male faculty members, an unusual number of single parents, abandoned children, and secret affairs, and a large percentage of rich, obnoxious students.’ All that seems to be missing are drive-through classes with burgers and fries served by retired professors. The most disenchanted of the fictional academics that Showalter writes about has to be James Hynes’ Nelson Humboldt, anti-hero and later hero of The Lecturer’s Tale (2001), who ‘had wanted to write his dissertation on Guilt and Predestination in the Works of James Hogg, but had been persuaded to write on Conrad and postcolonialism instead. Then he grinds out Hogg article after Hogg article, ending up with a book-length manuscript of unpublished and mutually exclusive chapters, each of which proved with equal conviction that James Hogg was a virgin and a libertine; a misogynist and an early feminist; hegemonic and transgressive; imperialist and postcolonial; patriarchal and matriarchal; straight, bisexual, and queer. Finally, he writes The Transgendered Calvinist: James Hogg in Butlerian Perspective and gives up scholarship in despair.’ But after Humboldt’s failure as a research scholar and his dismissal from his post, a supernatural phenomenon helps him reverse his fortunes, and like a Shakespeare comedy, all comes right in the end. The Lecturer’s Tale, then, unlike most other recent campus novels, offers a positive, if not a utopian world-view, with Nelson wondering if literature can change people’s lives. ‘Would The Great Gatsby raise their pay? Would Wuthering Heights lighten the burden of a dead-end job?’ We can never know. But Nelson decides, ‘this is both the enigma of teaching literature and its glory’. And I get the impression that Showalter agrees with him.

Faculty Towers, the academic novel and its discontents by Elaine Showalter is published by the Oxford University Press (ISBN 019928332X £12.99)

© Michael Lister 2005

Comments