Writing Young

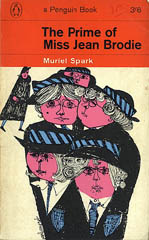

To claim Spark as a ‘Scottish writer’ tells only part of the truth. Much of Spark’s writing follows in the tradition of Hogg, Scott and Stevenson and some of her work shares the bitter, mordant economy and chilling darkness of the Border Ballads. Spark wrote in 2004 that, ‘no-one without knowledge of those Ballads could understand my work’. But it is also true that of her twenty-two novels, only one, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, is set entirely in Scotland, with two others – Symposium and Aiding and Abetting – being set partly there.

To claim Spark as a ‘Scottish writer’ tells only part of the truth. Much of Spark’s writing follows in the tradition of Hogg, Scott and Stevenson and some of her work shares the bitter, mordant economy and chilling darkness of the Border Ballads. Spark wrote in 2004 that, ‘no-one without knowledge of those Ballads could understand my work’. But it is also true that of her twenty-two novels, only one, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, is set entirely in Scotland, with two others – Symposium and Aiding and Abetting – being set partly there.

Although ‘Scottish both by birth and formation’, and a writer who wrote with ‘a Scotch accent of the mind’ that is unmistakably discernible in her work, Muriel Spark was much, much more than a ‘Scottish writer’. She was one of the finest twentieth-century novelists writing in English and an innovator with an international reputation. In recognition of this, the Scottish Arts Council has established the Muriel Spark International Fellowship. The announcement of the first holder of this fellowship, Margaret Atwood, was made only a few weeks before Spark’s death in April 2006.

Born Muriel Sarah Camberg in Edinburgh in 1918, she was to say that ‘it was Edinburgh that bred within me the conditions of exiledom’. These conditions took her first to Africa at the age of nineteen, after which Scotland was never to be her home again. Not without many connections, affiliations and associations for Spark, Edinburgh also became for her that ‘place that I, a constitutional exile, am essentially exiled from’. That sense of exile, as well as her deeply felt experience of it, informed her career as a writer, which began in earnest after she left Rhodesia for post-war London and took up an appointment with the Poetry Society as its General Secretary, combining with this the editorship of the society’s Poetry Review.  She brought youth and vitality to this near-fossilised institution with her enthusiasm for contemporary poetry and energy as a moderniser. For more than a year, her attempts to drag the society into the twentieth century met with fierce opposition from some of her colleagues and council members. Throughout this difficult period, Spark required it of herself to exercise nothing but tact and to respond to her critics with absolute charm until ‘her face ached of it’. Worn down by the old guard, she eventually asked to be dismissed rather than resign. (Some details of this far from dull period can be read in Spark’s volume of autobiography, Curriculum Vitae, published in 1992.)

She brought youth and vitality to this near-fossilised institution with her enthusiasm for contemporary poetry and energy as a moderniser. For more than a year, her attempts to drag the society into the twentieth century met with fierce opposition from some of her colleagues and council members. Throughout this difficult period, Spark required it of herself to exercise nothing but tact and to respond to her critics with absolute charm until ‘her face ached of it’. Worn down by the old guard, she eventually asked to be dismissed rather than resign. (Some details of this far from dull period can be read in Spark’s volume of autobiography, Curriculum Vitae, published in 1992.)

This new freedom gave her room to write, and she started her own publication, Forum, a magazine for poems and short stories. Although Forum ran for only two issues, it featured work by Roy Campbell, Kathleen Raine, Hugo Manning and Henry Treece. Now being published regularly in several poetry magazines herself, Spark was admitted to the Society of Authors in March 1949. She was also submitting poems to major London publishing houses for publication in a single volume. But from all these publishers came polite refusals.

A major improvement in her fortunes took place in 1951 when she won The Observer short story competition with ‘The Seraph and the Zambesi’. This is a surreal tale about a world where things are not as they seem, and which features a poet, a dancer, a Seraph and the Zambesi River, on which the Seraph rode ‘among the rocks that look like crocodiles and the crocodiles that look like rocks’. Almost 7,000 writers entered for the then huge prize of £250 and the promise of publication. This award was not only to change the course of Spark’s career as a writer; it was also to change the course of literary history.

Of course, Spark’s first appearance in print had taken place over twenty years earlier, in 1930, at the age of twelve, when five of her poems were published in The Door of Youth, a collection of poems by Edinburgh schoolchildren, with a foreword by the poet, novelist and politician John Buchan. Spark’s poems in that collection, and those she wrote during the 1930s for Gillespie’s High School Magazine, are as remarkably confident as they are technically accomplished. But her success in The Observer competition encouraged the Hand and Flower Press to publish her first collection of poems, The Fanfarlo, and other verse, in 1952, which was reviewed warmly in the Times Literary Supplement early the following year. Her poems were also published in the TLS from time to time.

Despite a period of ill-health, she remained immensely productive, writing literary biography, and continuing to write poetry. She had already published, with Derek Stanford, Tribute to Wordsworth; and there followed her own Child of Light, a reassessment of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley; and, with Stanford again, My Best Mary, selected letters of Mary Shelley; a study of the Poet Laureate John Masefield, whose Edinburgh public reading she attended as a schoolgirl; an edition of Brontë letters; and, also with Stanford, a selection of letters of John Henry Newman and a critical study of Emily Brontë.

Aided by the generosity of Graham Greene, who had read some of her stories and who sent her regular cheques, ‘with a few bottles of red wine to take the edge off cold charity’, Spark completed her first novel, The Comforters, in 1956. Published early the following year, it was generally well-received by the critics. Evelyn Waugh ‘offered a glowing quotation for publicity and an equally generous review’. He had been working on a novel on a similar subject to Spark’s, and went as far as to say, ‘I was struck by how much more ambitions was Miss Spark’s, and how much better she had accomplished it.’

There followed in the next four years, eight new works: five novels, Robinson, Memento Mori, The Ballad of Peckham Rye, The Bachelors and the pivotal The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, which Spark was to describe not unkindly as ‘her milch cow’; a selection of the poems of Emily Brontë; a collection of short stories; and ‘stories and ear pieces’.

In her hugely productive literary career, Spark was to publish, in addition to her works of biography and criticism, twenty-two novels, several collected editions of short stories, and a respectable amount of poetry. But it is for her novels – their startling originality, wit, verbal brilliance and technical assuredness that she is most remembered.

What is consistently true about Spark is that there never was a time when she was not doing something remarkable in her novels. In terms of themes, she explored the world of the supernatural and the endless struggle between good and evil. She produced several plots about the business of novel-writing itself, and, in terms of technique, she subverted conventional lines of narrative, using the devices of flash-forward or flash-back to create a sense of dislocation between present, past and future. These devices, and ‘the movement between past and present’, Anthony Burgess said, ‘created a view of reality that was Godlike’. Spark’s ‘extraordinarily daring time-shifts backwards and forwards across the chronological span of action’, combined with her distinctive feature of ‘prophetic glimpse of the future fate of her characters’, the novelist David Lodge described as ‘mimicking the omniscience of God who alone knows the beginning and the end.’ He wrote, ‘this does not serve the purposes of pat moralism or a reassuring providential pattern. It unsettles, rather than confirms, the reader’s ongoing interpretation of events, and constantly re-adjusts the points of emphasis and the suspense in the narrative.’ The brilliance of Spark’s technique as storyteller was also paid due tribute in the citation of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, when she was admitted as an honorary member: ‘her novels display an absolutely confident and economical style, an uncanny insight into human character, and a highly individual philosophical zeal that never wearies of exploring the vanities of civilised hellishness.’

Commenting ten years ago about how some readers tended to misjudge her age, Spark wondered if she ‘wrote young’. In her final novel, The Finishing School, published in 2004, she demonstrated, with her highly original vision and voice, that she did continue to ‘write young’.

© Michael Lister

This article was first published in 2006 in The Edinburgh Star, the magazine for the Edinburgh Jewish Community, and is reproduced with kind permission of its editor.

Comments