David Ionivich Bronstein

Grand Master

I was saddened by the recent news that David Bronstein, chess player, author and artist, had passed away. He was 82 years old, which is a good knock for a chess player. I’ve always believed one should celebrate a life rather than mourn a death of old age.

I was saddened by the recent news that David Bronstein, chess player, author and artist, had passed away. He was 82 years old, which is a good knock for a chess player. I’ve always believed one should celebrate a life rather than mourn a death of old age.

First, the ‘Bluffer’s Guide’ to David Bronstein’. David Bronstein was born in the Ukraine in 1924. He first became known to the chess world in 1940 when he was one of the youngest Soviet players to be awarded the National Master Title.

Eleven years later he earned the right to challenge fellow Russian, Mikhail Botvinnik, for the Chess Championship of the World. After twenty-four games the score stood at 12-12 and Botvinnik retained his title. Twice he won the USSR championship outright, the strongest chess tournament in the world, and on numerous other occasions finished in the top three.

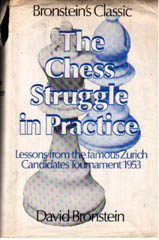

He wrote what has been hailed as one of the greatest chess book ever written

The Chess Struggle in Practice, often referred to as ‘Zurich 1953.’ Thrice married, he was very popular both with his fellow players and the chess public due to his imaginative play and his very easy nature. He was pleasant, charming, patient and sociable with a ready smile for everyone.

So, suitably armed, you can now enter a circle of chess players and drop into the conversation ‘Bronstein played some great games,’ and you will be met with knowing nods. But beware. Mentioning Bronstein to gain friends and impress your uncle can backfire.  You may suddenly have to find an answer to, ‘Did he fall or was he pushed?’, ‘How much of Chess Struggle is his?’ or ‘Did he really get the idea at the breakfast table?’ There are many questions that can be asked about the mystery that was David Bronstein.

You may suddenly have to find an answer to, ‘Did he fall or was he pushed?’, ‘How much of Chess Struggle is his?’ or ‘Did he really get the idea at the breakfast table?’ There are many questions that can be asked about the mystery that was David Bronstein.

‘Do you think Ian Fleming had Bronstein in mind when he named the chess player ‘Kronstein’ in From Russia with Love? (K for Kremlin and ‘ronstein’ from Bronstein) refers to one of the famous Bronstein myths and I will defuse it here. The chess players in From Russia with Love are Kronsteen (the villain and winner of the game) and McAdams. The game used in the film is based on Spassky v Bronstein, USSR Championship, Leningrad, 1960.  Bronstein lost the game thanks to some brilliant play by Spassky. This game opened with a King’s Gambit. Bronstein forgot that Spassky sometimes played the King’s Gambit and played some questionable moves. In Chess Improviser Boris Vainstein suggests that Bronstein could not bring himself to use the most critical variations against his favourite opening. He loved the King’s Gambit, but to try to dismantle it was, for him, like ‘killing a child’.

Bronstein lost the game thanks to some brilliant play by Spassky. This game opened with a King’s Gambit. Bronstein forgot that Spassky sometimes played the King’s Gambit and played some questionable moves. In Chess Improviser Boris Vainstein suggests that Bronstein could not bring himself to use the most critical variations against his favourite opening. He loved the King’s Gambit, but to try to dismantle it was, for him, like ‘killing a child’.

This gives an interesting insight into the complex, romantic character of Bronstein.  The position used in the film differs slightly. The producers removed two white pawns. This has brought forth all kinds of speculation: to make the win more impressive the pawns were lost or stolen… they were found on the grassy Knoll. From Russia with Love was the last film President Kennedy saw before he was assassinated. He saw a private showing at the Whitehouse on 20th November 1963. John Henderson, a columnist for The Scotsman, revealed all with his fine piece on Tuesday 12th December 2006. He wrote that the producers thought there was copyright on chess games so they removed two white pawns to make the positional original. There is no copyright on chess games.

The position used in the film differs slightly. The producers removed two white pawns. This has brought forth all kinds of speculation: to make the win more impressive the pawns were lost or stolen… they were found on the grassy Knoll. From Russia with Love was the last film President Kennedy saw before he was assassinated. He saw a private showing at the Whitehouse on 20th November 1963. John Henderson, a columnist for The Scotsman, revealed all with his fine piece on Tuesday 12th December 2006. He wrote that the producers thought there was copyright on chess games so they removed two white pawns to make the positional original. There is no copyright on chess games.

Did he really get the idea at the breakfast table?

This is the famous game Bronstein – Rojahn, Moscow Olympiad, 1956. In a position that had been known to chess opening theory for more than 100 years, in a variation named after Paul Morphy who is regarded as one of the greatest players that ever lived, Bronstein found a piece sacrifice on the 8th move and won a brilliant game. Bronstein said the idea for the piece sacrifice came to him while he was having breakfast on the morning of the game.

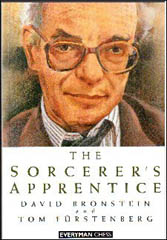

In The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, a collection of his best games, Bronstein’s co-author Tom Furstenberg says Bronstein wanted the game left out. ‘I am tired of this game.’ said Bronstein. Furstenberg slipped it in without notes towards the back of the book.  I have something strange to add here. I used to have the book Chess Improviser by Boris Vainstein, which was written in 1983. It is a collection of Bronstein’s games, including Bronstein – Ljubojevic, Petropolis, 1973. I actually wrote in my copy that this is a terrible game: ‘I could have done this… overblown analysis… what a lousy game.’ I donated the book to the Edinburgh Chess Club library. Somebody pulled me up for defacing it with my absurd comments. I replied that when I did so it was my book and I would do it again.

I have something strange to add here. I used to have the book Chess Improviser by Boris Vainstein, which was written in 1983. It is a collection of Bronstein’s games, including Bronstein – Ljubojevic, Petropolis, 1973. I actually wrote in my copy that this is a terrible game: ‘I could have done this… overblown analysis… what a lousy game.’ I donated the book to the Edinburgh Chess Club library. Somebody pulled me up for defacing it with my absurd comments. I replied that when I did so it was my book and I would do it again.

The game actually won a brilliancy prize but it is just a butcher’s hack, not a Bronstein classic. The sacrifices could be made without a moment’s thought. Ugly, obvious and brutal. Not Bronstein. Imagine listening to the complete works of Mozart and in the middle somebody has slipped in ‘The Birdy Song’, that’s Bronstein – Ljubojevic, Petropolis, 1973.

Furstenberg states that Bronstein argued with him about one other game he did not want in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice: Bronstein – Ljubojevic, Petropolis, 1973. I was so pleased when I read that. There are 222 games in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Bronstein and I agree which one should not be in it.

It only made it in because Bronstein found out that his great friend Paul Keres liked it. Of course, I’m not claiming Bronstein and I were kindred spirits. Most likely, he was fed up talking about the game, seeing it in print and being asked to comment on it. In his mind, and that of others, he had played much more beautiful and pleasing games of chess than this one. He wanted to be remembered for some of his other creations, not for this dog’s dinner. Mind you, having just written that ‘we agreed’ the game should not be in the book, leaving it out would have been ridiculous.

Did he fall or was he pushed?

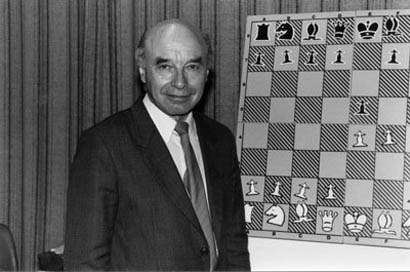

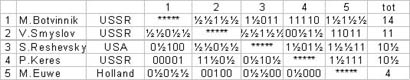

This refers to the 1951 World Championship match against Botvinnik. The claim is that pressure was applied to Bronstein by the Soviet authorities so that their man, Botvinnik, would win. Here are some facts but I do urge the reader to keep an open mind. First, we have this interesting picture of  Bronstein, Keres and Botvinni. Second, we have to touch upon a piece of relevant chess history. In 1946 the current World Chess Champion, Alexander Alekhine, died. FIDE, the chess governing body, held a tournament inviting the world’s best players to determine the new World Champion. The players were: M.Botvinnik, P.Keres, V.Smyslov (USSR) S.Reshevsky and R.Fine (USA) and M.Euwe (Dutch). This is not the place to discuss why other strong players were not invited but it is claimed that the USSR chose the line up.

Bronstein, Keres and Botvinni. Second, we have to touch upon a piece of relevant chess history. In 1946 the current World Chess Champion, Alexander Alekhine, died. FIDE, the chess governing body, held a tournament inviting the world’s best players to determine the new World Champion. The players were: M.Botvinnik, P.Keres, V.Smyslov (USSR) S.Reshevsky and R.Fine (USA) and M.Euwe (Dutch). This is not the place to discuss why other strong players were not invited but it is claimed that the USSR chose the line up.

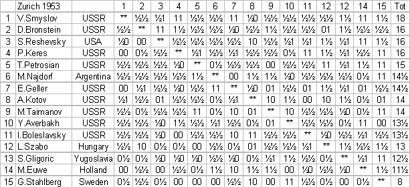

Originally everybody had to play each other four times but Rueben Fine pulled out so it was agreed to play each other five times. Botvinnik emerged as the winner and was awarded the World Title. The play of the brilliant Estonian player, Paul Keres, immediately became the subject of speculation. He lost four games to Botvinnik with uncharacteristic play. In Keres’s 5th game Botvinnik had by then won the tournament and could not be caught – Keres beat him. This fuelled rumours that Keres took a dive. Before 1948 Keres and Botvinnik had met 12 times over the board.

Losing 6, drawing 6 and no wins. Perhaps Botvinnik was simply the better player? Years later, shortly before his death in 1975, western journalists again asked him about his play in 1948. He stated that he was under instructions not to win the tournament.

Here is the tournament table.

A candidate’s tournament was held in 1950 to find a challenger for Botvinnik. This ended in a tie between Bronstein and Issak Boleslavsky. Bronstein won the play-off.

In The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Bronstein claims that Boleslavsky, who was wining the candidates, deliberately ‘slowed down’ to enable Bronstein to catch him up.

Boleslavsky was afraid of Botvinnik. Bronstein added that winning the right to play Botvinnik may have been a mistake, ‘but most likely I saved my friend from a certain defeat, possibly even humiliation.’ Bronstein’s third marriage was to Boleslavsky’s daughter Tatiana in 1984.

So we have Botvinnik against Bronstein: Botvinnik, the party member who received a telegram from Stalin for winning the challenging 1936 International Tournament in Nottingham against Bronstein, the Jewish son of a state criminal. Iohonon Boruch Bronstein, Bronstein’s father, was arrested on the 31st December 1937, ‘for defending peasants against corrupt officials,’ according to Furstenberg. Sentenced to hard labour in the Gulag he was released due to ill health in 1944. By then the Bronstein family were living in Moscow but Iohonon was still ‘banned’ and could not live or work within the city limits. He obtained a job in a factory forty kilometres from Moscow but this was still classed as within the city limits. He bribed the head of the local police to turn a blind eye.

During the match Mr and Mrs Bronstein were placed in the front row within sight of the challenger.  Two incidents from the match stand out. Games 1 to 4 are drawn. Bronstein wins game 5.

Two incidents from the match stand out. Games 1 to 4 are drawn. Bronstein wins game 5.

In game 6, in a position that a class D. player could draw, Bronstein suddenly thinks for forty-five minutes, plays the worst move of his career, and resigns a few moves later. The match see-saws. Botvinnik leads, Bronstein pulls level and takes the lead in

Game 22. He just has to draw the last two games to win the title.

So we come to famous 23rd game. I pass you across to Bronstein himself:

I have been asked many, many times if I was obliged to lose the 23rd game and if there was a conspiracy against me to stop me from taking Botvinnik’s title. A lot of nonsense has been written about this. The only thing that I am prepared to say about all this controversy is that I was subjected to strong psychological pressure from various origins and it was entirely up to me to yield to that pressure or not. Let’s leave it at that.

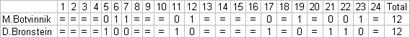

The 23rd game was adjourned with Botvinnik in the better position. Botvinnik sealed his next move (when a game of chess is adjourned a player puts his next move inside a sealed envelope. This is the move played when play resumes). The sealed move was not the best and Bronstein had a chance to draw the game. This time it was not so easy but well within Bronstein’s capability. He failed and lost the game. The 24th game was drawn. The match ended 12-12 and Botvinnik retained the title because Bronstein failed to beat him. Here is a breakdown of the World Championship match 1951.

Botvinnik does not come out of this episode smelling too clean. However, there are two sides to this story. Botvinnik was a great player. He never had the artistic flair of Bronstein but his technical play was perfect. His endgame play was far better than Bronstein’s and it was in the endings that the two important incidents took place. Salo Flohr, Botvinnik’s second/aid during the match, recalls the adjournment of the fateful 23rd game. Flohr assumed Botvinnik had sealed the best move and spent the night analysing and polishing the win. In the morning Botvinnik asked Flohr to show the winning variation to his wife. Flohr was confused because Gannochka Botvinnik barely knew how the pieces moved. However, Flohr showed the winning variations, starting with the best-sealed move. As he climbed onto the stage to resume the 23rd game, Botvinnik turned to Flohr and said, ‘You know, Salo, I sealed a different move.’

Flohr now understood Botvinnik’s strange behaviour. He was saying goodbye to his World Title. He wanted his wife to know that he had a chance of winning the game.

He expected the game to be drawn and Bronstein to be the next World Champion. So if there was anything shifty going on in the background, Botvinnik certainly did not know anything about it. I like to add here that if Botvinnik was ‘in on it’ and the match was rigged, then he could have gone to the authorities and got them to change the weaker sealed move.

The pressure that Bronstein spoke of could relate to the fact that his first marriage to International Chess player Olga Ignatieva was over and he was deeply in love with another women. If he won the title then divorce would have been out of the question. Also, he feared the non-chess publicity surrounding his private life might bring his father’s plight back to the attention of the authorities. Those were difficult times for the Russian people. In 1955, three years after Bronstein’s father had passed away, Mrs Bronstein received a letter informing her that the case against her husband was closed and that no crimes were ever committed by him against the State.

I have to mention another ‘run in’ with the Soviet authorities. In 1976, just after Viktor Korchnoi defected, Bronstein refused to sign a letter condemning Korchnoi’s actions. He lost the salary that the Russian State paid to its Masters and was forbidden from entering chess tournaments in the West for a number of years.

How much of ‘The Chess Struggle’ is his?

In 1992 I had over five hundred chess books, but I decided to sell them all bar ten. The Chess Struggle was one I kept and it really is a magnificent chess book. But did Bronstein write it? No, well not all of it. In an interview with Antonio Gude in 1993, Bronstein states:

Most of the nice words and elegant expressions in the book overall are the work of Vainstein, who writes very well… Of course the analysis and technical concepts are mine, as are the views on my rivals, but it may be said that a large part of the text is by Vainstein. Also, it is a book for which I do not have a particular affection because it reminds me of a tournament that was very special in a negative sense. Things happened there that I should like to forget… We shall discuss that another time. I do not wish to be more specific for the moment.

Vainstein actually writes a short essay in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice dated 1984. He refers to the Chess Struggle, calling it Bronstein’s book, and never hinting at all that he co-wrote it. Vainstein is possibly hedging his bets. The reason why his name never appeared on the original title was because he too had fallen foul of the authorities and was persona non grata. As for the Bronstein interview and his statement: ‘Things happened there that I should like to forget.’ This most likely refers to Bronstein’s claim that officials had pressured him and other Soviet grandmasters in the closing rounds to draw quickly with Smyslov, whilst playing hard against the American Samuel Reshevsky. Here is the tournament table for Smyslov v Fellow Russians.

So what will David Bronstein be remembered for? Bronstein himself often complained that he would be remembered for two numbers, 12-12 and 1953. When I read over this piece I notice that I have fallen into this trap. However, if I wanted to write a tribute then I felt I had to cover these events, if only to clean up Botvinnik’s name and clear up the question of authorship. Bronstein will be remembered for the pioneering work he did on the King’s Indian: an opening that was always regarded as ‘trappy’ and unsound by his peers. Bronstein, with the help of Boleslavsky, fashioned and honed this opening into a tough fighting defence against 1.d4. Three future World Champions, Tal, Fischer and Kasparov all relied heavily on the King’s Indian. Bronstein stubbornly believed in this opening and risked it in open tournament play. Without Bronstein this fantastic opening may have laid buried under ‘irregular openings’ and hundreds of beautiful and exciting games this opening has produced would have been lost to us.

He must also be remembered for his willingness to enter chess tournaments that other Grandmasters would shun. Here he is playing in the 1995 Manchester Open along with the rest of the punters.  Bronstein’s fellow Grandmasters usually refrained from playing alongside ‘patzers’ in cramped and occasionally noisy conditions. Bronstein even played in the London league representing Charlton. He simply loved playing chess.

Bronstein’s fellow Grandmasters usually refrained from playing alongside ‘patzers’ in cramped and occasionally noisy conditions. Bronstein even played in the London league representing Charlton. He simply loved playing chess.

I started this piece by calling Bronstein a chess player, author and artist. Some of his games really are works of art, beautiful creations, wonderful to play over. His games inspire you, they amuse you, they make you so glad that you know the game of chess and feel bitterly sorry for anybody who does not. He was a Magician

… a Sorcerer.

© Geoff Chandler, 2006

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Everyman Chess. ISBN 1857441516.

The Chess Struggle in Practise. Batsford. ISBN 0713424966

Comments