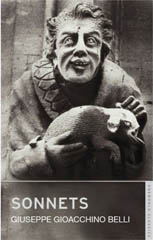

Giuseppe Gioacchino Belli

Sing Saucy Muse

In the nineteenth century, during his sojourn in Rome, they made Gogol laugh out loud when he heard them recited. In France, Sainte-Beuve admired them. While in England, Frances Eleanor Trollope, sister-in-law of the novelist, made translations of a minutely small number of the more respectable ones. In the twentieth century, D.H. Lawrence is said to have wanted to translate them himself, but lacked the particular linguistic skills to do them justice; William Carlos Williams savoured their ‘intimate tang’ and enjoyed their ‘ironic candour…in an idiom which had no classical pretensions’; Anthony Burgess made his own versions in what he termed ‘English with a Manchester accent’; and in the latter part of last century Robert Garioch and William Neill made turnings of them into Scots. Now, Mike Stocks presents his own impressive translations of some sixty of Belli’s Roman dialect sonnets, in a twenty-first century vernacular that is no less vibrant and vivid and versatile than the dialetto romanesco of two centuries ago.

In the nineteenth century, during his sojourn in Rome, they made Gogol laugh out loud when he heard them recited. In France, Sainte-Beuve admired them. While in England, Frances Eleanor Trollope, sister-in-law of the novelist, made translations of a minutely small number of the more respectable ones. In the twentieth century, D.H. Lawrence is said to have wanted to translate them himself, but lacked the particular linguistic skills to do them justice; William Carlos Williams savoured their ‘intimate tang’ and enjoyed their ‘ironic candour…in an idiom which had no classical pretensions’; Anthony Burgess made his own versions in what he termed ‘English with a Manchester accent’; and in the latter part of last century Robert Garioch and William Neill made turnings of them into Scots. Now, Mike Stocks presents his own impressive translations of some sixty of Belli’s Roman dialect sonnets, in a twenty-first century vernacular that is no less vibrant and vivid and versatile than the dialetto romanesco of two centuries ago.

Giuseppe Gioacchino Belli (1791-1863) composed well over two thousand Romanesco sonnets on what Frances Trollope called ‘almost every conceivable phase of Roman life,’ (and what Burgess was to say were, ‘all about dirty cynical suffering rejoicing Rome, and all in Roman voices.’) Trollope was one of the first English writers to recognise Belli’s importance as a sonnet-writer in the lingua parlata of Rome, but what she made of the satirical, scandalous and scurrilous works, we do not know. It is possible that the only editions of Belli available to Trollope were the early, heavily bowdlerised ones and so she would be unaware of some of those sonnets that Mike  Stocks describes as having ‘the primary aim of putting on a virtuoso display of vulgarity.’ But even with a limited knowledge of his work, Trollope was able to recognise Belli’s greatness, attributing it to ‘simply the result of an extraordinary power of observation’ and acknowledging it as ‘a gift of realistic portraiture unsurpassed in the history of letters.’ Though bowled over by the vitality of these works, Trollope was not uncritical of the other writings, and regarded ‘the considerable number of poems written in good Italian (sic)’ as ‘mediocre when they do not fall below mediocrity.’

Stocks describes as having ‘the primary aim of putting on a virtuoso display of vulgarity.’ But even with a limited knowledge of his work, Trollope was able to recognise Belli’s greatness, attributing it to ‘simply the result of an extraordinary power of observation’ and acknowledging it as ‘a gift of realistic portraiture unsurpassed in the history of letters.’ Though bowled over by the vitality of these works, Trollope was not uncritical of the other writings, and regarded ‘the considerable number of poems written in good Italian (sic)’ as ‘mediocre when they do not fall below mediocrity.’

Ironically, during Belli’s lifetime only one of his Roman sonnets was published, with his consent, though some were circulated in manuscript form and promulgated in the readings that Belli gave at private gatherings. It is doubly ironic that given his resolve ‘to leave a monument that shows the common people of Rome as they are today’, Belli nevertheless stipulated in his will that after his death all his manuscripts were to be burned. Perhaps he was hedging, and hoped that his literary executors, ‘far from trying to destroy them or suppress them as ambiguously requested’, as Mike Stocks writes, would in fact ‘recognise the worth of his these sonnets

… and arrange for a selection of them to be published.’ And so Belli’s Romanesco work did survive and came to represent his monument, ‘gain[ing] a far higher reputation than his poetry in Italian.’ But then this is no surprise, given the exuberance, the bawdiness and the variety of these works and the Roman street-life that they celebrate.

Mike Stocks is both a novelist and a fine poet himself: his own sonnet collection, Folly was published earlier this year. In his translations of Belli, Stocks demonstrates great skilfulness in working within the tight sonnet form and an assuredness in his linguistic inventiveness and ingenuity.  The selection he includes here consists of a good number on biblical and religious themes, particularly the bitingly satirical anti-clerical ones, and some which depict scenes from everyday life – harmonious and otherwise. His translations speak for themselves in their celebration of the straightforwardly bawdy and the splendidly vulgar. The language of Belli is robust, vigorous, fresh, lively, spirited, spunky, even. Equally so, the language of Stocks’ translation. For example, his renderings of the two ‘anatomical’ sonnets – The Mother of Saintly Women and The Father of Saintly Men – represent an exhaustive lesson in the ‘naming of parts’, none of which will be found in any medical dictionaries, and are more likely to be seen scrawled on toilet walls.

The selection he includes here consists of a good number on biblical and religious themes, particularly the bitingly satirical anti-clerical ones, and some which depict scenes from everyday life – harmonious and otherwise. His translations speak for themselves in their celebration of the straightforwardly bawdy and the splendidly vulgar. The language of Belli is robust, vigorous, fresh, lively, spirited, spunky, even. Equally so, the language of Stocks’ translation. For example, his renderings of the two ‘anatomical’ sonnets – The Mother of Saintly Women and The Father of Saintly Men – represent an exhaustive lesson in the ‘naming of parts’, none of which will be found in any medical dictionaries, and are more likely to be seen scrawled on toilet walls.

There is the saying that ‘poetry is what gets lost in translation’, and the Italians have a particular take on the matter themselves: ‘tradure

è tradire’ – ‘to translate is to betray.’ And surrounding any poetry in translation are the vexatious questions of ‘accuracy’ and ‘faithfulness’ to the original. Without fluency in both Romanesco and English, it is not possible to ‘assess’ the ‘accuracy’ of Stock’s translations or their ‘faithfulness’ to Belli’s originals. But it is possible to read these translations alongside those of other poet-translators – say, Burgess’ and Garioch’s ‘Er giorno der giudizzio’ – ‘Judgement Day’ is as good an example as any. Stocks’ open with ‘four portly angels’ who ‘ plonk’ themselves down ‘at their ease’ at the four corners of the earth to ‘blow their horns’ – reminiscent, to me, of four rotund priests, amply satisfied after a good lunch, rounded off with port wine and brazil nuts. Garioch opens with ‘fowre muckle angels…stalkin the airts’. While Garioch’s vision is perhaps the more theologically sound – the stalking angels are certainly more Apocalyptic – Stocks’ has a reassuring feel. Despite what they herald, Stocks’ angels are, well, a bit more cuddly. Burgess’, on the other hand, opens with a kind of Miltonic inversion, keeping his simple ‘angels’ for line two. He doesn’t number them or name their instruments at the outset, but prefers to wait, before introducing a touch of the Mancunian by placing them in ‘a brass quartet.’ A most clever combination, but in no way faithful to the original.

For the image of the resurrected dead rushing about to ‘assume the bodies of their former times’ before the final great division, Stocks, in keeping with Belli, has his dead dash[ing] about like chicks around a hen.’ Garioch has ‘choukies gaitheran roun a hen that’s clockan’, while Burgess, with a touch of the grandiloquent, goes Milton-like on us with ‘There the All High, maternal, systematic,/Will separate the black souls from the white.’ Again, most clever, but not close to Belli’s humble farmyard hen. The final images Garioch translates as ‘Last sall come angels, swarms of them, in flicht,/and, like us gaean to bed without a swither,/will blaw out the caunnles, and guid-nicht.’ Stocks gives, ‘And last, there’ll be a big humdinging flight/Of angels who, as though it’s time for bed,/Will blow the candles out, and nighty-night.’ Both Stocks’ and Garioch’s have the echo of Shakespeare’s ‘Now cracks a noble heart. Good night, sweet prince, and flights of angels sing thee to they rest’; but, as if like Dryden, Burgess has ‘wing’d musicians’ who, in a kind of onomatopaeic (and now decidedly much less Dryden-like) ‘er-phwoo

…put out the light.’ Combining a sense of both massive size and volume of sound, Stocks’ ‘humdinging flight’ is a masterstroke – suggestive and more of Belli’s ‘sonajera’, meaning ‘anthill’ (replicated by Garioch as ‘swarm’) and which figuratively also means a ‘baby’s rattle’, in this case presumably a giant baby’s giant rattle.

Certainly Stocks’, like Garioch’s, are more faithful to the originals in content, tone, diction and form. (Burgess, never one to content himself with a mere translation, sets out to outdo Belli, going his own way to compose an original sonnet based on an idea of Belli’s.) But we digress. In their inventiveness and ingenuity, Mike Stocks’ spirited translations are sure to bring new visitors to this great monument of Belli’s. Entrance charge only £8.99, with unlimited access and great fun guaranteed.

© Michael Lister

Sonnets: Giuseppe Gioacchino Belli. Translated by Mike Stocks. Oneworld Classics. ISBN 9781847490117. £8.99

Comments