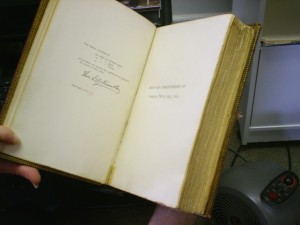

Sir Arthur Ponsonby

Chronicles of Small Beer: Some Early Scottish Diaries

The earliest surviving Scottish diaries date from the late 16th and early 17th centuries, and we owe their publication to such excellent learned societies as the Bannatyne Club, the Maitland Club, the Spalding Club and the Scottish History Society who have rescued them from oblivion and printed them with explanatory introductions, notes and glossaries. Many diaries still lie in manuscript in libraries and family archives, and it may be that masterpieces still await discovery and publication. The vast collection of Boswell’s diaries had to wait for two hundred years before it was discovered at Malahide Castle in Ireland, and it was published as recently as the 1950s; and Kilvert’s Diary, surely the most readable ever written, was only printed some seventy years after Kilvert’s death. It is unlikely that a Boswell or a Kilvert will be discovered among the unpublished Scottish diarists, for the writing of a diary in the 17th century seems to have been a Protestant replacement for the Catholic confessional. Most of them are repetitive recitals of the diarist’s sinfulness, usually imaginary, and make gloomy reading. The voluminous diary kept by Archibald Johnston, Lord Wariston, during the reign of Charles I and under Cromwell’s Protectorate, is typical of its period. Johnston was described by Carlyle as an ‘austere Presbyterian Zealot, full of fire of heavy energy and of gloom’. He was one of the framers of the National Covenant in 1638, but he was obsessed by his own sinfulness and unworthiness and assured God that he was ‘the unworthyest, fillthiest, passionatest, deceitfullest, crookedest, backslydingest, rebellionest, perjurest, unaiblest of all His servants’. (Such honesty is rare among modern politicians). Never a man to use one word where ten could be used, Johnston was afflicted by ‘sorrow, grief, tears, comfortlessness, heartlesnes, solitarines and melancholy,’ and ‘roared and youled pitifully’ when his first wife, Jean, died at the age of fifteen after only a year of marriage. True, she had been no beauty, her face being ‘al spoiled by the poks’, but when he had put her through an examination of her religious knowledge in their marriage bed, he had been ‘ravished by her answers’. He soon recovered from his sorrow, grief, etc., etc., and within a year married a more mature and wordly lady, Helen May. He sired thirteen children, and although family prayers could occasionally last for a full two hours, there was, sadly, backsliding that had to be reprimanded. ‘I spak my mynd sharply to my wyf and her daughter against their promiscuous dancing at the marriage, and was glayd to sie it did affect my daughter’. But not, apparently, his wife. It was not a happy family. Johnston’s religious zeal could not compensate for his incompetence in money matters and as the family fortunes declined his wife was forced to sell her ‘sylver-work to interteane the family’. Little wonder that she was often ‘oppressed with greife’ and ‘very cankered about our affaires’. His life ended on the gallows at the Market Cross in Edinburgh when he was executed after the Restoration for his support of Cromwell. His Diary makes depressing reading, but it was not intended for mortal eyes. Rather it was Johnston’s apologia to his Maker.

The earliest surviving Scottish diaries date from the late 16th and early 17th centuries, and we owe their publication to such excellent learned societies as the Bannatyne Club, the Maitland Club, the Spalding Club and the Scottish History Society who have rescued them from oblivion and printed them with explanatory introductions, notes and glossaries. Many diaries still lie in manuscript in libraries and family archives, and it may be that masterpieces still await discovery and publication. The vast collection of Boswell’s diaries had to wait for two hundred years before it was discovered at Malahide Castle in Ireland, and it was published as recently as the 1950s; and Kilvert’s Diary, surely the most readable ever written, was only printed some seventy years after Kilvert’s death. It is unlikely that a Boswell or a Kilvert will be discovered among the unpublished Scottish diarists, for the writing of a diary in the 17th century seems to have been a Protestant replacement for the Catholic confessional. Most of them are repetitive recitals of the diarist’s sinfulness, usually imaginary, and make gloomy reading. The voluminous diary kept by Archibald Johnston, Lord Wariston, during the reign of Charles I and under Cromwell’s Protectorate, is typical of its period. Johnston was described by Carlyle as an ‘austere Presbyterian Zealot, full of fire of heavy energy and of gloom’. He was one of the framers of the National Covenant in 1638, but he was obsessed by his own sinfulness and unworthiness and assured God that he was ‘the unworthyest, fillthiest, passionatest, deceitfullest, crookedest, backslydingest, rebellionest, perjurest, unaiblest of all His servants’. (Such honesty is rare among modern politicians). Never a man to use one word where ten could be used, Johnston was afflicted by ‘sorrow, grief, tears, comfortlessness, heartlesnes, solitarines and melancholy,’ and ‘roared and youled pitifully’ when his first wife, Jean, died at the age of fifteen after only a year of marriage. True, she had been no beauty, her face being ‘al spoiled by the poks’, but when he had put her through an examination of her religious knowledge in their marriage bed, he had been ‘ravished by her answers’. He soon recovered from his sorrow, grief, etc., etc., and within a year married a more mature and wordly lady, Helen May. He sired thirteen children, and although family prayers could occasionally last for a full two hours, there was, sadly, backsliding that had to be reprimanded. ‘I spak my mynd sharply to my wyf and her daughter against their promiscuous dancing at the marriage, and was glayd to sie it did affect my daughter’. But not, apparently, his wife. It was not a happy family. Johnston’s religious zeal could not compensate for his incompetence in money matters and as the family fortunes declined his wife was forced to sell her ‘sylver-work to interteane the family’. Little wonder that she was often ‘oppressed with greife’ and ‘very cankered about our affaires’. His life ended on the gallows at the Market Cross in Edinburgh when he was executed after the Restoration for his support of Cromwell. His Diary makes depressing reading, but it was not intended for mortal eyes. Rather it was Johnston’s apologia to his Maker.

Another Covenanting statesman of Johnston’s generation was Sir Thomas Hope. His Diary, kept between 1633 and 1646, was published by the Bannatyne Club in 1843. Less lachrymose and less given to dwelling on his sinfulness than Johnston, he was more of a family man – if less fecund – and often refers with affection to his sons, daughters and grandchildren, but not to his wife. When an infant grandson died at the age of a few days he was so stricken with grief that ‘my wyf was angrie at my griefe’, which is revealing. He often recounts his dreams which were quite unremarkable, not to say boring. He seems to have been accident prone. One day as he was sitting poking the fire, ‘the schyre quhairin I satt coupit and I gat ane heavie fall on my bak on the ground, but my heid was saiff’. And on the 22nd of March 1642 as he was reading with his back to a candle, ‘suddenlie my ruff tuik fyre, and brak furth in ane low, quhilk I preissit to quench, but could not, quhairvpon I cuist my gown from me, and ran down the bak passage crying for help, but gat none till I cam to the hall quhair the servandis cam furth, and speciallie James Twysdaill the stewart glaspit the low in his handis, and tuik my ruff from my craig, and so freed me off my fier, for quhilk I pray the Lord to mak me thankfull, for it wes a greit mercie’.

Another Covenanting diarist was Alexander Brodie of Brodie, Member of Parliament for the County of Elgin. He kept a diary meticulously every day, the last entry being made on the day of his death. Much of the diary has been lost, but what survives shows him as a more engaging personality than either Johnston or Hope. Like them he was convinced of his sinfulness and unworthiness, but he shows a charitableness and unwillingness to condemn others that was unusual in that stern age. He also had a love of the ‘earthly delights’ of ‘trees, plants and floures’, and was fond of gardening although he was fearful that this was a ‘sinful affection’.

In August 1672 he visited a healing well to drink the medicinal water, ‘desiring to use it as a means through His blessing to prevent the diseas which I am subject unto of the stone. I was this night at Burgi. Mr. Colin Falconer drank with me, and we recreated the bodi by pastim at golf’. But his conscience troubled him and he added: ‘Lord! let this be no snare to me’. Another endearing trait of Brodie’s is that although he lived at the height of the witch mania he ‘desired not to be lookd on as the pursuer of thes poor creaturs’.

Although Sir John Foulis of Ravelston kept no diary, his Account Book from 1671 to 1707 tells us more about his life than any diary and shows us a man of normal human interests and appetites, a man a thousand miles removed from the gloomy, sin-obsessed Puritans. Foulis treated his children (and his servants) to a visit to ‘Leith Wynd to see the puppie show’ (the newly arrived Punchinello, or Punch). He bought sugar candy and a golf club for his nine-year-old son, Archie; he twice went to see the elephant and paid 13s 6d to treat the animal to bread and ale. (This elephant, incidentally, had been bought in 1680 by some English entrepreneurs for the prodigious sum of £2,000, and seems to have lumbered its way around England and Scotland, attracting marvelling crowds). On several occasions Foulis lost money gambling at the ‘hoy jinks’, a convivial booze-up of lawyers held in Edinburgh every New Year. He was sufficiently fond of the ladies to buy sweetmeats for ‘Lady Collingtoun, Lady Mart, KcKenzie and others’. (£6 2s. they cost). He was generous, giving tips to the town drummers and pipers and to ‘poor scollars’. He loved every sort of entertainment, from watching ‘ane supple man’ (an acrobat) and a rope dancer in the street to visits to the theatre to see plays and comedies. In February 1672 he ‘payed for myselfe, my wife and Cristiane to see McBeth acted’. How he would have enjoyed the Edinburgh Festival.

William Cunningham of Craigends seems to have had much in common with Foulis, if we may judge from the careful Household Book that he kept between 1673 and 1680. He spent lavishly at the ‘chocollattee house’ for dishes of chocollattee and for sweeties and confits. He must have been a typical Restoration dandy, in his coat and ‘breeches of purpur cloath’ and his ‘Cawdebink hatt’ (from Caudebec in France). He spent unsparingly on clothes, not only for himself but also for his wife, for whom he bought an expensive nightgown. Like Foulis he loved play-going and entertainment and went to see the famous elephant when it appeared in Glasgow. One hopes that Foulis and Cunningham met, perhaps over a dish of chocollattee or at a puppie show.

The Diary of John Lamont of Newton in Fife, kept between 1649 and 1671 deals largely with events in Scotland but has some tasty items of gossip about fellow Fifers. Lady Wemyss, he tells us, ‘had a great desire after strong drink’ and had a ‘doore strucken through the wall of her chamber for to goe to the wine cellar’. The Earl ‘att her death was a hunder thousand mark worse then when he maried her, and all the time of the mariage was onllie two year’. Lamont tells how the Presbytery of St Andrews sacked the schoolmaster of Largo ‘for profainlie taking the name of the diuill in his mouth twyse, for ordinary tippling and drinking, and not praying euening and morning, in the schole, and also mutch guien to mockeing and taunting’. He was restored to his job by falling on his knees and confessing that the Lord was righteous. He tells us how, during the Cromwellian occupation of Scotland, the minister of Ceres, William Howe, was questioned by the Parliamentarian commissars about his loyalty. ‘Would he fight for the King?’ they asked. To which Mr Howe, a canny Fifer, replied that ‘he was not a good feghter, but he would pray for him and them, heartily, and they should have his best wishes’. They dismissed him. Lamont noted the appearance of ‘a desease not before this year [1650] knowen to the inhabitants of the kingdom. It was commonlie called the Irish Aygo, which was a terrible sore paine of the head, some saying that ther heads did open. The ordinarie remidie was the hard tying up of the head’. The Irish Aygo is still with us, now known as influenza. Hard tying of the head is no longer practised as a cure.

After the austerity of the Cromwellian dictatorship, the arts and popular entertainments flourished in Scotland during the Restoration. Puppie shows, supple men, wild beast shows and Shakespeare all drew crowds, long starved of colour and entertainment. Lamont describes the mountebanks who practised in the burghs of Scotland. In December 1662 he notes that ‘Ponteus, the mountebancke, was now the thrid tyme in Scotland, viz. 1. in Anno 1633; 2. in An. 1643; and now in An 1662 and 1663. Euery time he had his publicke stage erected, and sold theron his droggs to the peopell: the first tyme for 1 lib, the 2 tyme for 1lib 9s, the thrid for 18 pence. Each tyme he had his peopell that played on the scaffold, ane ay playing the foole, and ane other by leaping and dancing on the rope’. Another mountebank Lamont described, appropriately, as a ‘High’ German, ‘comeing downe ane high tow, and his head al the way downeward, his armes and feite holden out all the tyme; and this he did diuers tymes in one afternoone’.

One might have expected the Sir William Drumond of Hawthornden, son of the Cavalier poet, would have something interesting to say in his Diary. In fact, it is largely a tedious recital of his boozing. His entry for Saturday 16th May 1657 is typical. ‘Drank a hudge wine at owr coming hom escaped a denger of drowning by providence’. On their way home to Hawthornden from Edinburgh he and his pals seem to have fallen into the Esk, with the result that on Sunday ‘Munsie Achmutie and I stayed from church, our cloths being all spoyld by water’. Many an evening he spent at Hawthornden ‘solitarie and fatall’. ‘Fatall’ has been glossed as being a seventeenth century euphemism for blind drunk. It may well have meant something else. He tells us that ‘October, November and December was I taken up so bussilie in courtinge of my mistres, she whom prouidence gaue to be my wife, that I cowld not have time to write anie’. And after his marriage to Sophie Auchmutie, there is not more mention of solitarie and fatall evenings.

Of all the early Scottish diarists the only one to make a name in history is General Patrick Gordon. Born in Aberdeenshire in 1635, ‘the younger son of a younger brother of a younger house’, like many another ambitious young Scot he emigrated to Europe where he served as a soldier of fortune. He kept a daily record of his adventurous life for some forty years, but his account of his eventful life makes duller reading than Lamont’s gossip from Fife. Gordon served first in the Swedish army against the Poles, then in the Polish army against the Swedes. He finally settled in Russia where he became a general and the most trusted friend of Peter the Great. When he died in 1699 it was Peter the Great who closed his eyes and his funeral was one of almost royal magnificence. He met and talked with King James II, Queen Cristina of Sweden, Prince Rupert and the leading politicians of his day, but his diary is as pedestrian as a school-boy’s. His account of his departure from Scotland is typically unemotional: ‘After a sadd parting with my loveing mother, brothers and sister, I took my jorney to Aberdeen in company of my father and unkle, who, after two days stay, wherein I was furnished with cloths, money and necessaries, returned. My mother came foure days thereafter, of whom I received the benediction and tooke my leave’. Years later he revisited his homeland as a powerful Russian general. When he sailed from Aberdeen on his return to Russia, his diary has a line that has all the sadness of exile in it: ‘Yet he keeped sight of Scotland till neer night, and with sad heart bid it farewell’.

It is pleasant to turn from the sin-obsessed diarists of the 17th century to the sane everyday world of the Reverend George Ridpath, minister of the Border village of Stitchell near Kelso. Between the years 1755 and 1761 he kept a diary, which was published in 1922 by the Scottish History Society. It was edited by Sir James Balfour Paul who, in an inspired and almost surreal phrase, described it as ‘a chronicle of very small beer’, by which he meant that Ridpath dealt not with theology and philosophy but with his everyday home life. Not that Ridpath was an average Kirk of Scotland minister. He was a man of the Enlightenment, a friend of David Hume and John Home, the playwright. Although he carried out his duties as a parish minister conscientiously and duly gave the long, uninspired sermons expected by his parishioners, he noted in his diary that a magazine he had been reading contained nothing ‘except some silly articles on theology’. He read widely in the classics, on history, geography, science and especially on medicine. He kept a Medical Adversaria into which he copied any useful information he came across. In November 1759 when his little niece and nephew became ill with fever, apparently diptheria, he nursed them night and day. ‘I performed all the duty to her [Nancy] I could, by sitting up all the night by her, and from time to time administering to her some little draughts part of which she with great efforts got over’. In spite of his efforts the little girl died and ‘this scene of distress was scarce over when we learned that the poor boy had had feverish symptoms the preceding night, which continued still with him, tho gently in the morning. The Doctor took a sufficient quantity of blood from him; and as grief at first for the other poor child, and afterwards a sore throat and other distressing symptoms, the consequence of grief and of the cold and fatigue in attending poor Nancy, rendered my sister incapable of attending the boy, [Willie]. I set about this task and shall be always thankful to the Almighty for having been an instrument, if I am not mistaken, of preserving his life’. Ridpath described dispassionately how he nursed the child night and day, with little sleep, for nine days until the boy was out of danger.

In July 1760 Ridpath proposed to Minna Dawson ‘on the mossy turf, under a sweet grove’. She accepted him, but they were not married until 1764, by which time Ridpath had ceased to keep his diary, but we know that it was a happy marriage. Ridpath’s diary is a delightful record of a mere six years from a happy quiet life spent in helping his neighbours, playing with children, gardening, reading, scanning the skies with his telescope, buying lottery tickets in the hope of clearing his debts (he drew a blank ‘which puts an end to my castle building, in which I have often indulged since I was an adventurer in this affair’), spending convivial evenings with friends (including an evening with the notorious Lord Braxfield, when he ‘sate too long and drank a great deal too much’). Ridpath’s Diary is truly worthy of a place on the shelf beside the great Scottish diaries of the nineteenth century – Scott’s magnificent Journal, Jane Welsh Carlyle’s too-short effervescent Diary, and Queen Victoria’s delightful Journal.

Book List

British Diaries: An Annotated Bibliography of British Diaries written between 1442 and 1942 (University of California, 1950) by William Matthews lists some thirty Scottish diaries from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that have been printed.

These include:

Diary 1632-1660 Sir Archibald Johnston of Wariston, Scottish History Society, Edinburgh, 1896, 1911, 1919, 1940.

Diary 1652-1680 Alexander Brodie of Brodie, Spalding Club, Aberdeen, 1863.

Diary 1633-1646 Sir Thomas Hope of Craighall, Bannatyne Club, Edinburgh, 1843.

Diary 1649-1662 John Lamont, Maitland Club, Edinburgh, 1830.

Passages from the Diary 1655-1668 General Patrick Gordon, Spalding Club, Aberdeen, 1859.

Diary Sir William Drummond, Scottish History Society, Edinburgh, 1941.

Diary 1755-1761 George Ridpath, Scottish History Society, Edinburgh, 1922. (This last is worth reading in full; extracts from the others may be read in Scottish and Irish Diaries from the 16th to the 19th Centuries by Sir Arthur Ponsonby. London, 1927.)

© David Fergus

Reprinted from the Scottish Book Collector archives.

Comments