By

Mistresse of the Golden Pen

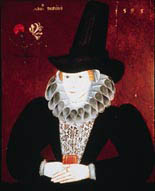

I first met Esther Inglis in the small shop at the National Library of Scotland. Straight off I loved her outfit. She was wearing a plain Elizabethan-style dress with a high ruff, and a most memorable black brimmed hat perched on her swept-back hairstyle. The postcard – for such she was – provided only the barest of information: ‘Self-portrait of Esther Inglis, the calligrapher, 1615.’

I first met Esther Inglis in the small shop at the National Library of Scotland. Straight off I loved her outfit. She was wearing a plain Elizabethan-style dress with a high ruff, and a most memorable black brimmed hat perched on her swept-back hairstyle. The postcard – for such she was – provided only the barest of information: ‘Self-portrait of Esther Inglis, the calligrapher, 1615.’

I took her home with me and for several years she has been blu-tacked to the kitchen wall, surveying us with the intense level look of a trained recorder. And so the matter might well have rested – life being full of lots of hares to pursue – if my daughter had not persuaded me to visit Holyrood Palace this past New Year’s Day. There, in an exhibition of illustrated books called ‘Winter Flowers’, I encountered my first exquisite Esther Inglis book.

The book, appropriately enough, was a New Year gift in 1607 to Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales. ‘Cinquante octonaires sur la vanite et inconstance du monde’, may not have particularly excited the young recipient but it was, as I later discovered, a favourite collection of moral verses much copied by Esther.

Alongside the glass case in which the book was displayed a notice provided more information . Esther Inglis was in fact a Huguenot, the daughter of Nicholas Langlois, master of the French school in Edinburgh. She learned calligraphy from her mother, and had changed her name from Langlois to Inglis.

The next stop naturally was the National Library where I found listed a little booklet on Esther Inglis by Dorothy Judd Jackson, privately printed by the Spiral Press, NY in 1937.

From DJJ I learned that lady calligraphers were abundant in the 16th and 17th centuries (though perhaps not in Scotland). Where Esther is exceptional is in the number of her signed manuscript books surviving. (DJJ knew of 41mss. The number now has risen to 50).

Even more interested in the woman than the calligrapher, I now learned that in 1596 she had married a Scotsman, Bartholomew Kello, who soon afterwards applied for the post of ‘Clerk of all Passports’ citing his wife’s calligraphic skills in his support. Bartholomew was an educated man, probably a graduate of St Andrews University, who could pen Latin verse in praise of his wife.

Other devotees of Esther were the academic heavyweights Andrew Melville, Robert Pollock, and John Johnston, principals of Glasgow, Edinburgh, and St Andrews Universities respectively, who all wrote laudatory verses to her virtue and skill. The astute Esther promptly included these in her books.

In 1606 she moved south to Willingale Spain in Essex where Bartholomew had secured the position of rector. They were back in Edinburgh in 1615 and Esther appears to have remained there till her death in 1624, at the age of 53.

In 1606 she moved south to Willingale Spain in Essex where Bartholomew had secured the position of rector. They were back in Edinburgh in 1615 and Esther appears to have remained there till her death in 1624, at the age of 53.

In her booklet DJJ noted that David Laing owned the unsigned warrant for Bartholomew Kello’s appointment as Clerk of all Passports and an oil painting of Esther Inglis both of which, she said, could no longer be traced.

And so in my pursuit of Esther Inglis I arrived metaphorically and inevitably at the door of David Laing, the indefatigable Scots antiquarian. A list of his writings during a long life, which encompassed most of the nineteenth century, now takes up a sizeable part of a microfiche in the NLS.

Edinburgh in particular is indebted to David Laing for his interest in Esther Inglis. He donated all five of her mss held by the university, buying one from a Leipzig bookseller, rescuing another in a mutilated condition at a sale in London. And the painting of Esther Inglis, dated1595, ‘fell into my hands accidentally at a sale in Edinburgh… without knowing from what collection it came, or who the painter was.’ It is now, DJJ would be relieved to know, safe in the National Portrait Gallery.

David Laing’s ‘Notes relating to Mrs Esther Langlois or Inglis, the celebrated calligrapher’ are to be found in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 1865/66 (pp284-309). There he states that the Langlois family were settled in Edinburgh by 1578, quoting payments from the Scottish treasury to Nicholas Langlois and Marie Prisott his wife.

Making a new start in a foreign country must have been tough for all of the family – even Esther never felt completely at ease with the English language – but Esther’s early troubles as a child of refugee parents were as nothing -compared to those of young Bartholomew Kello.

His father, John Kello, had been the first Presbyterian minister of Spott in East Lothian, and seemed settled there with his wife and three small children, Bartholomew, Barbara, and Besse. But on Sunday, 24th September 1570, tempted, he later said, by the suggestions of the evil spirit and not from any personal dislike, he strangled his wife.

David Laing gives a graphic account of the drama which ensued, as John Kello faked the hanging of his wife, locked the doors of his house, and went off to take the morning service as usual. When the corpse was discovered no suspicion fell on the minister (except from the minister at Dunbar to whom Kello had related strange dreams).

A week later, as remorse set in, John Kello confessed to the murder, was tried, executed, and his body burned on October 4th 1570. His estate was escheated and provision made for the care of his three children. When attempts were made abroad to use the affair for anti-Reformation propaganda John Kello’s confession was printed in which he warned ‘not to measure the truth of God’s word by the lives and folly of the preachers.’

The definitive list of the surviving mss of Esther Inglis, detailing content, binding, provenance, and present location is provided in the painstaking work of A.H. Scott-Elliot and Elspeth Yeo in Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America (vol 94 1990). They give the early date of 1569 for the Langlois family’s departure from France (three years before the infamous Bartholomew Day Massacre and two years before Esther’s birth). So Esther may well have been born in the parish of Blackfriars where the family is noted in the Returns of Aliens in 1571.

According to Scott-Elliot and Yeo the misfortunes of both sets of parents meant that Esther and her husband lived in straightened circumstances all their lives. Esther died in debt, which makes all the more poignant the dedication which she wrote in the last year of her life to the future King Charles I on his return from Spain.

‘My pen is now prepared to writte to your Highnesse the onlie Phoenix of this age. This kindled a desire in mee Sir, to caste my Myte into the Treasurye, as that poore widowe did, whom our Saviour commended, not considering how much, bu(t) of how much she offered, respecting rather ye affection of the giver, then the quantitie of the gift

… But remembring your Highnesse douce and sweet inclination I recovered againe the Spirit of an Amazon Lady, and it was my bounden deutie, to congratulat your Highnesse blessed saif, and most happie returne, and to offer to your Highnesse thir two yeeres labours of the small cunning that my totering (hand), now being in the age of fiftie three yeeres, might affoord.’

The 1612 payment of £22 from Prince Henry to Esther (or ‘Mirs Kelloo’ as she is rather endearingly named in the royal accounts) was possibly the equivalent of more than half her husband’s salary at Willingale Spain. Small wonder then if Esther felt a great responsibility upon her to use her skills for the betterment of her family.

None of her books appear to have been commissioned. Considering the work involved in each it must have been worrisome, once she had handed over one of her ‘guifts’, waiting to see what financial return it would bring.

When she went to Essex she targetted the local Lord Petre with a copy of the Octonaries and a grovelling dedication.

‘It may seem straunge to your Honour that I a stranger unknown to you should present you with anything proceeding from me: yet having consecrated sum labours of my pen and pensill to the highest and noblist of this land, ass weel to sundrie of the Peers of this Realme, as to the King’s Majestie and to the Prince his Grace unto whom they have bene ver gratious and acceptable and synce it hath pleased Almighty God to bring me to thir parts hard by your Honour I have presumed altho unacquainted with your Honour to prepare and dedicat this work.’

We can only hope Lord Petre took the hint.

Another dedication in a new year’s gift in 1606 of a Selection from Proverbs to the ‘Vertuous Lady Arskene of Dirltoun’ could perhaps have been more tactfully put, beginning as it does ‘altho yea have perchance neither seen nor hard of me yit your noble and wordy Lord has both.’ (Spelling was, incidentally, never Esther’s strong suit, no doubt a result of a tri-lingual mix of French, Scots, and English.) She ends her dedication to Lady Arskene with the comment ‘If I knowen your Ladyship had bene a student in french I should have made this in the samin language.’

Another dedication in a new year’s gift in 1606 of a Selection from Proverbs to the ‘Vertuous Lady Arskene of Dirltoun’ could perhaps have been more tactfully put, beginning as it does ‘altho yea have perchance neither seen nor hard of me yit your noble and wordy Lord has both.’ (Spelling was, incidentally, never Esther’s strong suit, no doubt a result of a tri-lingual mix of French, Scots, and English.) She ends her dedication to Lady Arskene with the comment ‘If I knowen your Ladyship had bene a student in french I should have made this in the samin language.’

Her skill as a calligrapher is unquestioned. Scott-Elliot and Yeo describe it as extra-ordinary. As well as the more usual hands, she had mastered most of the ornamental styles, including lettera mancina (mirror writing), lettere piacevolle (with curling terminals to ascenders and descenders), lettre pattee with triangular serifs, the trembling line known as lettera rognosa, and lettera tagliata where each line is broken horizontally to give a continuous white line through the letters.

Esther could work to the minutest scale, fitting eight lines into a vertical measurement of only 18mm, and averaging 23 words to a four-inch line. Metal pens were at an experimental stage, so that goose pens, with crow quills for finer work, were mainly used. The description of Esther as ‘Mistresse of the Golden Pen’ is complimentary only. Gold pens were awarded as prizes for major writing competitions.

Her smallest book, only 47mm by 31mm and bound in embroidered green velvet, is a brief synopsis of the bible and is dedicated ‘To my well loved Sonne Samuel Kello this great little book do I recommend.’

Of the 50 surviving books, 44 are in their original bindings. Esther may have bound her own books, and to save expense almost certainly embroidered those in silk and velvet. She first used colour in 1601 for one initial letter in Les Proverbes de Salomon, in 1605 for a single rose in Hume’s Vincula Unionis, and thereafter from 1605 to 1615 on every page, in finely observed drawings of flowers, insects, and birds. The naturalistic design of her title pages, Scott-Elliot and Yeo observe, probably derive from Flemish or French Books of Hours.

Esther sometimes included a self-portrait. There are 24 such small portraits, with an open book, a sheet of music, a lute, or a pen and inkpot to emphasise her cultural credentials. She also often added a self-effacing inscription, ‘De Dieu (or De l’Eternel) le Bien, de moy le mal ou rien’.

Esther’s books are now to be found in libraries throughout the world. No less than 21 are in the United States, 10 are in England, and 9 in Edinburgh (3 in the NLS, 5 in the university library, and one deposited in the Scottish Record Office by the Clerk family of Penicuik) with France, Germany, Sweden, and Denmark each having one example.

Six books are in private hands and five are untraced. Edinburgh could add to its count if the copy of Les Cinquante Octonaires, which disappeared from the Advocates Library ‘sometime between 1892 and October 1912′, could be located.

The time had now come for me to hold an Esther Inglis book for myself. Of the three in the NLS one is a book of examples of handwriting, considered by David Laing to be linked to Esther Inglis, the second is Les Lamentations de Ieremie with the coat of arms of the Earl of Argyll, bought at Christie’s in 1986 and rebound in brown morocco.

The third is the real treasure. Les Pseaumes de David, escrits à Londres par Esther Inglis pour son dernier adieu, ianvier 1 1615. (Two of her children had died the previous year, and she herself may have been ill. Hence the pessimistic note.) Inside a little box was this tiny book, 90mm by 60mm, in original maroon velvet embroidered with silver thread, with central medallions on both covers of a phoenix. Scarcely daring, I turned the pages marvelling at the minute writing and suddenly found myself looking at my postcard lady, in brighter colours and only the size of my thumbnail.

There remained only one more document to see in the NLS. This is the petition by Esther Inglis in 1620 to James I pleading for his help on behalf of her ‘only sonne’ who was anxious to study theology. It is vintage Esther, as she wraps her request in the contrived conceit of comparing her son to Didelus.

Didelus, she writes ‘was not hable to frie him selfe of his imprisonment in the Ille Creta but by the help of wings mead of pennes and wax even so my sonne is not able to frie himself of inhabilitie to effectuate this his affection but by the wings of your Maties letter composed by pen and waxe through the which he may have his flight happilie to sum fellowship either in Cambridge or Oxefoord.’

If the King grants her petition, Esther concludes, ‘I may have my tossed mynd releeved of the great cair I have perpetuallie for this said youth.’

As I held Esther’s petition in my hand, I thought of the somewhat rare occurrence of a telephone call the previous evening from my son during which he inquired solicitously after my health before mentioning a temporary cash-flow problem which was coinciding with rent day for his flat in Edinburgh.

Nothing much changes in family relations I decided as I left the NLS to meet my ‘only sonne’ for what might prove to be a rather expensive pub lunch.

© Margaret Macaulay 2002

Comments