By

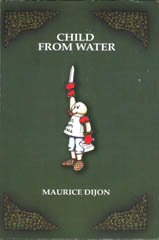

Boy in the Bucket

Child From Water is ‘the first part of book 24 of The Pugnaceid‘. Queen Pugnaceia is at the height of her queenly powers and beauty, and decides she will and must have an assembled history of the legendary Wezuls who came before her. She summons her court and demands it be so; they weasingly comply, and their narrative is the start of the tale of the Child From Water. The Child, also known as The Child Roland, arrives from the sea wearing an upturned bucket with holes cut out for his arms, as prophecy foretold. He attempts to befriend Scum, those who have been cast out to live in the treacherous Derdang forest, to help him in his mission to overthrow the evil Baron (he who did the casting out).

Child From Water is ‘the first part of book 24 of The Pugnaceid‘. Queen Pugnaceia is at the height of her queenly powers and beauty, and decides she will and must have an assembled history of the legendary Wezuls who came before her. She summons her court and demands it be so; they weasingly comply, and their narrative is the start of the tale of the Child From Water. The Child, also known as The Child Roland, arrives from the sea wearing an upturned bucket with holes cut out for his arms, as prophecy foretold. He attempts to befriend Scum, those who have been cast out to live in the treacherous Derdang forest, to help him in his mission to overthrow the evil Baron (he who did the casting out).

It is difficult to pass critical judgement on something that feels like a joke gone surprisingly well, from cover to cover. But there are many things to consider. Child From Water got written the way ‘Maurice Dijon’ envisaged, and we can like it or ‘fegg off’. His prologue, written with considerable hauteur, affects the style of an academic treatise on some obscure and forgotten tribe. There is certainly enough persuasion and invention to make you, sort of, believe that Wezul Studies is indeed taught in some small devoted department somewhere. For a few seconds, you really want to believe.

All too often the writing is that of someone who believes that everything they say is pure gold, beginning, ‘I’m sick to death of this introduction’ and ending, ‘I’d like to thank everybody who’s helped me… But I have a party to go to and life’s too short anyway.’ The author, peppering his tale with not infrequent asides of ‘Merde!’ and ‘There I go again’, evidently expects we will embrace his every quirk with liberal relish rather than simply endure his solipsism.

The attempt of Queen Pugnaceia’s Wezul court to right historical wrongs and restore honour provides the main narrative drive, but present time punctuates: the court argues, somebody takes over the telling of the yarn, the history exposing the roots of what comes. Unfortunately, the characters are annoying, not least the youthful hero, aka the Boy in the Bucket. Bossy, obnoxious little beast! The Scum are backstabbing brutes. Baron Urming of Uzzabor is a boil-pocked baddie of Bond villain proportions. In short, cliches abound.

With talk of ‘gloids’ and ‘belboggens’, being ‘morkit’ and evil ‘puggies’, the language is like Scots and German and a strange Vikonic slang all rolled into one onomatopoeic burst. There is surprising poetry in it. A glossary is provided for your edification, or perhaps to remind you that you are reading an ‘academic’ (hee hee) text. Fantasy fans will appreciate Dijon’s inventive grappling with philology and knowing take on the genre but he’s not everyone’s flagon of mead.

Comments