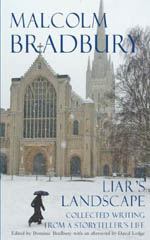

Malcolm Bradbury

Liar’s Landscape

It comes as a relief to me to know that I am not the only reader to have occasionally confused Malcolm Bradbury with David Lodge. Any such confusions were only ever momentary. Where others might have, I never conflated the two writers to create a third ‘conceptual compound’, the well-known novelist ‘Blodge’, whose books we all claim to know but cannot quite bring the titles to mind.

It comes as a relief to me to know that I am not the only reader to have occasionally confused Malcolm Bradbury with David Lodge. Any such confusions were only ever momentary. Where others might have, I never conflated the two writers to create a third ‘conceptual compound’, the well-known novelist ‘Blodge’, whose books we all claim to know but cannot quite bring the titles to mind.

In the afterword to this collection, David Lodge pays tribute to his friend and ‘literary twin’ Bradbury, who died in 2000, and writes, ‘this book belongs to the genre that used to be called, rather lugubriously, ”literary remains”, though being by Malcolm Bradbury it is not at all lugubrious in effect.’

Indeed it is not. It affirms the man and his life and is typically eclectic, consisting of a selection of the unfinished work and uncollected stories that lay in Bradbury’s study, and which his son Dominic enumerates as ‘an idea for a novel on Cold War spies in the genteel world of academia, a handbook on creative writing, a compilation of short stories, a book on the fiction of the fifties

… and a fragment of a novel, Liar’s Landscape.’

Very much a book about books and writing and writers, it is also in essence a book about Bradbury himself. He writes with gratitude about his parents, about his father’s love of trains, and the trip he takes in his memory on the Royal Scotsman. In his tribute to his mother he says, ‘I still look for qualities like hers, considerate, thoughtful and restrained, in the women, and the men, I meet.’ Again with a kind of gratitude he remembers his schooldays, and in his short piece ‘In Praise of Grammar Schools’ does not so much regret the passing of these institutions, which he acknowledges as divisive and elitist in a sense, but makes a much more urgent and passionate point about the future of education, which much of Bradbury’s life was so bound up with: a beneficiary of the 1944 Butler Education Act, and a ‘scholarship boy’, he avoided Oxbridge by studying at Leicester University, and began teaching at Hull. Then from Birmingham he was famously poached by East Anglia, where he co-founded with Angus Wilson the creative-writing MA course, having already established himself as one of the wickedest proponents of the English satirical ‘campus’ novels. The rest, they say, is ‘history, man.’

Alongside the biographical pieces are some short stories and journalism, and the fragment of the novel which gives the collection its title. In ‘Welcome Back to the History Man’, Bradbury muses on the creation he brought into the literary world and assesses the damage that his own Frankenstein, Howard Kirk, is said to have wreaked on the academic community, particularly in the field of sociology, which, some claim, ‘has not really recovered its authority.’ Though he seems flattered to be considered a player, Bradbury considers the larger picture and the more obvious reasons for the demise of sociology.

‘The Wissenschaft File’ is the place where Bradbury kept his letters from foreign students from ‘any one of the European countries where they study contemporary literature in a decidedly energetic and theoretical sort of way.’ So convincing is it, that it might just not be a spoof. But it is. Bradbury concedes too early that it is merely an example of the type of letter he receives in his daily post.

Much of the journalism is devoted to the craft of fiction-writing and to writing about fiction: ‘Reading Parties’, ‘Do We Have Great Novels Anymore?’, ‘A Modest Proposal’ and ‘Mortal Fictions’ all approach the relationship between reader and book from different angles, but converge at the same point: that fiction is a good. ‘We are not short of novels

… creative writing, too, is everywhere

… the novel is still many things

… reading is always helped by talking about it

… readers multiply the meanings of books

… a great novel can be simple, or difficult, but first and foremost it is not an imitation, it is a book that has its own inner voice.’ Bradbury as critic and academic was attuned to that ‘inner voice’, which in his own creative writings he was able to express.

Lodge writes, Liar’s Landscape is ‘a book for readers who already know and love Bradbury’s work, and cherish every bit of it; who will be grateful that a substantial amount of his fugitive journalism has been preserved, engaged by the autobiographical memoirs, and fascinated by the unpublished stories and fragments of unfinished work-in-progress.’ Bradbury’s son, in his introduction, having explained that ‘this book evolved from clues from my father’s desk. … Assembled over time, with love and regret, I wish I could ask Malcolm Bradbury, father and writer, if this compilation feels right to him.’ Most readers familiar with Bradbury’s life and work will think it would have done.

Liar’s Landscape: collected writing from a storyteller’s life by Malcolm Bradbury, edited by Dominic Bradbury, with an afterword by David Lodge. Picador (ISBN 0330435329 HBK £20)

© Michael Lister 2006

Comments