Annie Wilson and the Roslin Inn

Annie Wilson was the landlady of the Roslin Inn, where she lived with her husband Daniel. Over the years they played host to a dizzying array of artists, poets and writers, including Dr Samuel Johnson, James Boswell, Sir Walter Scott, William and Dorothy Wordsworth, Alexander Nasmyth and Robert Burns. Picturesque tours of the antiquities of Britain were then becoming all the rage, and the Wilsons provided an earthy welcome to the growing army of visitors. It was said that the Roslin Inn was ‘a very shabby House, dirty and uncomfortable,’ but Annie’s hospitality was legendary. She served an impressive Scotch breakfast that included cold fowls, hot beef steaks, tongue, rolls, toast, jelly and marmalade.

Annie Wilson was the landlady of the Roslin Inn, where she lived with her husband Daniel. Over the years they played host to a dizzying array of artists, poets and writers, including Dr Samuel Johnson, James Boswell, Sir Walter Scott, William and Dorothy Wordsworth, Alexander Nasmyth and Robert Burns. Picturesque tours of the antiquities of Britain were then becoming all the rage, and the Wilsons provided an earthy welcome to the growing army of visitors. It was said that the Roslin Inn was ‘a very shabby House, dirty and uncomfortable,’ but Annie’s hospitality was legendary. She served an impressive Scotch breakfast that included cold fowls, hot beef steaks, tongue, rolls, toast, jelly and marmalade.

An article from the September 1817 edition of the Gentleman’s Magazine includes a sketch of the formidable Annie, the ‘venerable damsel of Caledonian nativity.’ She wears a floor length dress, an apron, shawl and bonnet; with her hunchback, hook nose and jutting chin, she resembles the archetypal fairytale witch. The writer noted that ‘Annie Wilson recites the Latin Epitaphs with apparent facility; but her pronunciation is so harsh and discordant, that to an English ear it is quite unintelligible.’

She would recount the legend of Rosslyn’s murdered Apprentice in gory detail, then stride around the chapel reading the Latin epitaphs from the tombs of the St Clairs. Visitors were well advised to listen intently as ‘if any thing in the way of interruption comes across her, she commences once more her elegant demonstration, her narrative of the Apprentice’s Pillar, with ‘his head bearing the scar just about the brow that his master made upon it, his mother’s head represented as if bewailing the death of her son, and the Apprentice’s master’s head, just before he was hanged.’

In the sketch Annie is pictured with her ubiquitous ‘divining rod,’ which she used to point out the carved heads of the Apprentice and his grieving mother, and sometimes tipped with a piece of sponge soaked in red ochre, with which she would add vivid splashes of ‘blood’ to the gash cut in the Apprentice’s forehead. Annie would deliver her dramatic performance in a broad local accent:

There ye see it with the lace bands winding sae beautifully roond aboot it. The maister had gane away to Rome to get a plan for it, and while he was away his prentice made a plan himself and finished it. And when the maister came back and fand the pillar finished, he was sae enraged that he took a hammer and killed the prentice. There you see the prentice’s face up there in the corner, wi a red gash in the brow, and his mother greetin for him in the corner opposite. And there, in another corner is the maister, as he lookit just before he was hanged; its him wi a kind o ruff roond his neck.

Sir Walter Scott and his friends Gilles and Erskine were both shown around the chapel by Annie. During one visit Erskine whispered to Scott that ‘as habitual visitors, perhaps they would escape the usual endless story of a silly old woman that showed the ruins!’ Scott answered, ‘There is pleasure in the song which none but the songstress knows. By telling her we know it already, we should make the poor devil unhappy.’

For thirty pounds a year Scott rented a thatched cottage at nearby Lasswade Village, where he went each summer to escape the hustle and bustle of Edinburgh. He would sit in his country retreat to write, walk in the woods, tend the garden, and fish in the river Esk.

From his little rural idyll Scott visited Dalkeith Palace, Hawthornden Castle, and Woodhouselee. At Lasswade he worked on The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, collecting ballads and local traditions from old people, manuscripts and printed chapbooks. He had initially planned to include the tale of the fair Rosabelle in the Minstrelsy, but eventually it appeared in The Lay of the Last Minstrel.

Tens of thousands of copies of The Lay of the Last Minstrel were published. Its unprecedented success established Scott as a renowned poet and brought sightseers to Scotland to visit Melrose Abbey and Rosslyn Chapel.

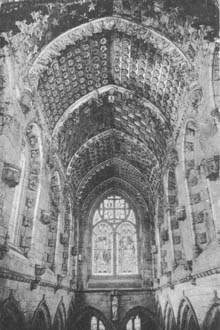

In 1803 Scott was visited by his friend William Wordsworth, and his sister Dorothy. The chapel was a romantic ruin; its windows were shuttered; green moss and lichens covered its carvings. In Dorothy’s ‘Recollections of a Tour made in Scotland’ she gives a vivid account of the chapel:

The stone of both roof and walls is sculptured with leaves and flowers, so delicately wrought that I could have admired them for hours, and the whole of their groundwork is stained by time with the softest colours. Some of those leaves and flowers are tinged perfectly green, and at one part the effect was most exquisite – three or four leaves of a small fern, resembling that which we call Adder’s Tongue grew round a cluster of them at the top of a pillar, and the natural product and the artificial were so intermingled from the other, they being of an equally determined green, though the fern was of a deeper shade.

Dorothy noted in her diary that the architecture within the chapel was ‘exquisitely beautiful.’ Her brother was preoccupied by the dreadful Scots weather that accompanied their visit. In a footnote to his poem ‘Composed at Roslin Chapel during a storm,’ he said:

We were detained, by incessant rain and storm, at the small inn near Roslin Chapel, and I passed a great part of the day pacing to and fro in this beautiful structure, which, though not used for public service, is not allowed to go to ruin. Here this sonnet was composed, and [I shall be fully satisfied] if it has at all done justice to the feeling which the place and the storm raging without inspired. I was as a prisoner. A Painter delineating the interior of the chapel and its minute features, under such circumstances, would have no doubt found his time agreeably shortened. But the movements of the mind must be more free while dealing with words than with lines and colours. Such, at least, was then, and has been on many other occasions, my belief; and as it is allotted to few to follow both arts with success, I am grateful to my own calling for this and a thousand other recommendations which are denied to that of the Painter.

Robert Burns and the painter Alexander Nasmyth visited Roslin early one summer’s morning in 1787. Nasmyth’s son James recounted the story of their visit in his autobiography:

On one occasion my father and a few choice spirits had been spending a nicht wi’ Burns. The place of resort was a tavern in the High Street, Edinburgh. As Burns was a brilliant talker, full of spirit and humour, time fled until the ‘wee sma’ hours ayont the twal” arrived. The party broke up about three o’clock. At that time of the year the night is very short, and morning comes early. Burns, on reaching the street, looked up to the sky. It was perfectly clear, and the rising sun was beginning to brighten the mural crown of St Giles’s Cathedral.

Burns was so much struck with the beauty of the morning that he put his hand on my father’s arm and said, ‘It’ll never do to go to bed in such a lovely morning as this! Let’s awa’ to Roslin Castle.’ No sooner said than done. The poet and the painter set out. Nature lay bright and lovely before them in that delicious summer morning. After an eight-miles walk they reached the castle at Roslin. Burns went down under the great Norman arch, where he stood rapt in speechless admiration of the scene. The thought of the eternal renewal of youth and freshness of nature, contrasted with the crumbling decay of man’s efforts to perpetuate his work, even when founded upon a rock, as Roslin Castle is, seemed greatly to affect him.

My father was so much impressed with the scene that, while Burns was standing under the arch, he took out his pencil and a scrap of paper and made a hasty sketch of the subject. This sketch was highly treasured by my father, in remembrance of what must have been one of the most memorable days of his life.

After a serious night in Edinburgh’s taverns, an eight mile walk in the small hours, and a roam around Roslin Glen, Burns and Naysmith sat down to breakfast at the Roslin Inn. They took tea, eggs and some whiskey. Naysmith noted in a letter to William Cribb that ‘the charge was very moderate in our opinion.’ Burns was clearly impressed by the eccentric Annie. On finishing his breakfast he scratched a poem onto a pewter plate:

In 1806 a ten year old boy named George Meikle Kemp visited Roslin Chapel. He would have met Annie Wilson and listened as she recited the story of the Master Mason and the Apprentice. She told exactly the same tale to every visitor until her death in the 1820s. Kemp became a self-taught architect and eventually entered an architectural competition to design a commemorative monument to Sir Walter Scott. His winning design, Edinburgh’s famous Scott Monument, was inspired by the gothic stonecarvings of Rosslyn Chapel.

Mark Oxbrow is co-author of Rosslyn and the Grail, with Ian Robertson. It is published by Mainstream Publishing, ISBN 1845960769 HBK £15.99.

© Mark Oxbrow 2006

Guest blog by Professor Patrick Scott: ‘At Roslin Inn’ - Editing Robert Burns for the 21st Century on Thu, 7th Jun 2018 10:34 am

[…] and Roslin Inn,’ Scottish Book Collector (2006), now available on the Textualities site at: http://textualities.net/mark-oxbrow/annie-wilson-and-the-roslin-inn. On the general issue of Burns facsimiles, which are not listed in Egerer, see my ‘A Neglected […]