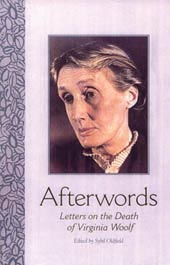

Afterwords

Afterwords brings together for the first time the letters Leonard Woolf received on the death of Virginia. These letters of condolence, housed in the Monks House, and the Leonard Woolf Papers in the University of Sussex, are presented in this collection in five sections: letters from Virginia’s circle; from Leonard and Virginia’s shared circle; from Leonard’s circle; from the general public; and from Vanessa Bell’s circle. The editor, Sybil Oldfield, writes, ‘the condolence letters here … being private, personal responses to the death of Woolf, read very differently from public obituaries and newspaper commentaries. For it is in many of these letters that we find what Keats called ‘the true voice of feeling’ and sympathy, described by George Eliot as that one ‘poor word which includes all our best insight and our best love.’

Afterwords brings together for the first time the letters Leonard Woolf received on the death of Virginia. These letters of condolence, housed in the Monks House, and the Leonard Woolf Papers in the University of Sussex, are presented in this collection in five sections: letters from Virginia’s circle; from Leonard and Virginia’s shared circle; from Leonard’s circle; from the general public; and from Vanessa Bell’s circle. The editor, Sybil Oldfield, writes, ‘the condolence letters here … being private, personal responses to the death of Woolf, read very differently from public obituaries and newspaper commentaries. For it is in many of these letters that we find what Keats called ‘the true voice of feeling’ and sympathy, described by George Eliot as that one ‘poor word which includes all our best insight and our best love.’

To use a term from recent literary theory, Afterwords contains a ‘polyphony of voices’ united in a common narrative – here the many voices at work express friendship, love, sympathy, loyalty and a shared sense of profound loss, as well as deep admiration. These emotions are conveyed with admirable control and much dignity and mostly with a great simplicity of language, which to some might appear as a kind of understatement, though that is perhaps the quintessence of Englishness in matters surrounding death. (And the letters from the small group of Rodmell neighbours particularly demonstrate that very English sense of ‘community’. Each of these short letters begins very formally, ‘Dear Mr Woolf’ or ‘Dear Sir’, and each remains very formal and correct in its content and expression. None of the Rodmell letters intrudes on personal grief nor makes claims on Virginia for other than she was, a neighbour.)

The ‘polyphony of voices’ in the letters in Afterwords represents the extent of the Woolfs’ circle of friends and acquaintances – nearly all the English writers who mattered, as well as the ‘great and the good.’ From reading these missives one is reminded just how much both Virginia and Leonard were at the heart of English letters and society, despite the open hostility they experienced from various quarters. Virginia Woolf’s massive reputation was, of course, well-established, long before her life came to an end, and in her lifetime her unique contribution has been appreciated critically. There is nothing posthumous about Woolf’s reputation, and as one correspondent wrote to Leonard, ‘she gave much which has been of value to the world, and what she gave will endure.’ After reading Orlando and The Waves, the Indian writer Tagore had already said, many years before her death, ‘Mrs Woolf is creating a tradition in literary English style,’ and on her death TS Eliot wrote that ‘for myself and others it is the end of a world.’ Despite the achievements of Bloomsbury, this group of intellectuals had from the outset been regarded by the British Establishment with great suspicion. During WWI its members and adherents had been villified as ‘pacifist shirkers.’ A few days after the coroner’s inquest, Virginia Woolf was attacked in the Sunday Times by the wife of an English Bishop, who insulted Woolf’s memory by declaring that she lacked backbone and had let the side down. This was on the Bishopess’s reading of a misreporting of Virginia’s suicide note. And just two days before The Times announced Woolf’s disappearance, a National Labour MP in a parliamentary debate denounced a certain section of British writers and artists as being like Fifth Columnists. At this time in particular, most British intellectuals were, as a matter of course and on principle, roundly despised merely for being intellectual. (Plus ça change…) But in Afterwords, the expressions of support from the number of great intellectuals and from ‘Common Readers’ alike, who all wrote in sympathy to Leonard, matter much more and are of longer-lasting importance than any silly letters to the press from Bishops’ wives or dangerous speeches made in Parliament about the ‘traitors within.’ Besides, by the time Virginia Woolf was being attacked alongside other writers and intellectuals in the House of Commons, as being one who did the work of a fifth columnist, she was already dead.

All the letters in this remarkable collection are profound expressions of authentic feelings. Sybil Oldfield points out that, ‘by their very nature condolence letters cannot constitute a genre. Every authentic, deeply felt condolence letter has to be so intensely subjective, written uniquely by A, addressed solely to B, and focussed on the one and only C, that by definition each letter must be profoundly different from another.’

Each letter in Afterwords is indeed profoundly different from every other. Those writers and intellectuals who wrote to Leonard on the death of Virginia were already established figures in the literary and intellectual scenes and all now can be found in the new Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. They include: Edmund Blunden, Elizabeth Bowen, Frances Cornford, TS Eliot, EMForster, Radclyffe Hall, Harold Laski, John Lehmann, Rose Macaulay, Naomi Mitchison, Gilbert Murray, Harold Nicolson, Vita Sackville-West, the Sitwells, s

Comments