By

Unfinished Business

The Stevenson Collection has an interesting history. Its core consists of items acquired by Charles John Guthrie, Lord Guthrie (1849-1920), a contemporary of Stevenson, a fellow student at Edinburgh University and fellow candidate for admission to the Scottish Bar in 1875. In 1908 Guthrie became tenant of Swanston Cottage (the Stevenson family’s summer home from 1867 to 1880), and stayed there and in the New Town. By the time of his death in 1920 he had acquired a large collection of Stevenson material through personal contacts and through correspondence with a wide circle of Stevenson’s friends and relatives.

Guthrie had been active in the formation of the Robert Louis Stevenson Club and its acquisition of 8 Howard Place, where Stevenson was born. He had intended the collection to be housed there but he died before testamentary provision was made to this effect. Consequently the tenancy of Swanston Cottage reverted to the owners, the Edinburgh and District Water Trust, and the collection became its property on the understanding that it would be lent to the Stevenson Club when Howard Place was ready for display. This was not until June 1926, by which time the Water Trust had been taken over by Edinburgh Town Council, making the collection the property of the City. The display was transferred from Lady Stair’s House to Stevenson’s birthplace, where it remained until the early 1960s. More items were added during this period but in 1962 diminishing income led to the decision to sell the property. The council was asked to resume custody of the original Guthrie Collection and the bulk of the later acquisitions, to be housed once more in Lady Stair’s House, alongside the Burns and Scott collections.

Guthrie had been active in the formation of the Robert Louis Stevenson Club and its acquisition of 8 Howard Place, where Stevenson was born. He had intended the collection to be housed there but he died before testamentary provision was made to this effect. Consequently the tenancy of Swanston Cottage reverted to the owners, the Edinburgh and District Water Trust, and the collection became its property on the understanding that it would be lent to the Stevenson Club when Howard Place was ready for display. This was not until June 1926, by which time the Water Trust had been taken over by Edinburgh Town Council, making the collection the property of the City. The display was transferred from Lady Stair’s House to Stevenson’s birthplace, where it remained until the early 1960s. More items were added during this period but in 1962 diminishing income led to the decision to sell the property. The council was asked to resume custody of the original Guthrie Collection and the bulk of the later acquisitions, to be housed once more in Lady Stair’s House, alongside the Burns and Scott collections.

The Stevenson Collection is the only such collection on this side of the Atlantic. Objects from the author’s early life include a book awarded as a school prize, his kaleidoscope and a toy theatre. There is a hand-coloured example of Skelt’s sheets for Juvenile Drama – New Smugglers – purchased by him as a boy from a stationer’s at Union Place. Stevenson discussed his passion for drama in the essay ‘A Penny Plain and Twopence Coloured’:

The Stevenson Collection is the only such collection on this side of the Atlantic. Objects from the author’s early life include a book awarded as a school prize, his kaleidoscope and a toy theatre. There is a hand-coloured example of Skelt’s sheets for Juvenile Drama – New Smugglers – purchased by him as a boy from a stationer’s at Union Place. Stevenson discussed his passion for drama in the essay ‘A Penny Plain and Twopence Coloured’:

What am I? What are life, art, letters, the world, but what my Skelt has made them. He stamped himself upon my immaturity. The world was plain before I knew him, a poor penny world; but soon it was all coloured with romance.

Left:The Edinburgh Writers’ Museum

An unusual item of interest in the collection is a cabinet or gentleman’s wardrobe made by the infamous Deacon William Brodie (hanged in 1788). This piece of furniture was in the Stevenson family home in Heriot Row and its associations played on the delicate little boy’s vivid imagination. It is mentioned in the play he co-wrote with W.E. Henley, Deacon Brodie, or, the Double Life, a melodrama in five acts, first produced in Bradford in 1882. The cabinet was presented by RLS to Henley. Sold by Henley’s executors in 1903 for £20, it was subsequently bought by Lord Guthrie in 1912 for £25. The theme of the dual personality always fascinated Stevenson, reaching its full maturity in The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

Suffering from sporadic bouts of severe ill-health all his life, Stevenson is often thought of as an invalid, but in actual fact he was very active when he was not laid low. One of his outdoor pursuits was fishing and the collection includes his fishing rod and basket. He recounts what would have been his last experience of fishing in a letter to J.M. Barrie, written from Vailima in 1894:

I had always been accustomed to pause and very laboriously to kill every fish as I took it. But in the Queen’s River I took so good a basket that I forgot these niceties; and when I sat down… to take my sandwiches and sherry, lo! and behold, there was the basketful of trouts still kicking in their agony. I had a very unpleasant conversation with my conscience. All that afternoon I persevered in fishing, brought home my basket in triumph, and sometime that night, ‘in the wee sma’ hours ayont the twal’, I finally forswore the gentle craft of fishing.

Left:Painting of Vailima on display at the Edinburgh Writers’ Museum

Stevenson certainly didn’t allow himself to be molly-coddled if he could help it. As a young man he travelling widely in Britain and Europe and met his future wife, Fanny van de Grift Osbourne, in France in 1876 and eventually followed her to America – an arduous journey of twenty-one days by boat and train – described in Across the Plains. They were married in San Francisco in May 1880.

In the collection is the Davos Press – a small hand-operated printing press, first used in San Francisco, and taken to Edinburgh and Davos, Switzerland, where Stevenson spent two winters in his search for health; there he and his stepson Lloyd Osbourne printed invitation cards, concert programmes and booklets of stories and poems, such as The Graver and the Pen and Moral Emblems, embellished with woodcuts by Stevenson himself.

Following the death of his father in 1887, Stevenson, his wife, mother and stepson undertook the first of several cruises among the islands of the South Seas. These cruises are documented in photographs, mainly taken by Lloyd, and preserved in albums which came into the Stevenson Collection in the 1930s, one by purchase, the others from Lloyd Osbourne himself.

Left:The Davos Press

The first cruise on the Casco involved taking a typewriter and photographic equipment with which to document their travels. The second cruise on board the trading schooner Equator was intended to be more intensive. Stevenson planned an illustrated work, to be called The South Seas, detailing the history and anthropology of the whole area.

By the time I am done with this cruise I shall have the material for a very singular book of travels:masses of strange stories and characters, cannibals, pirates, ancient legends, old Polynesian poetry; never was so generous a farrago. (June 1889, Letters, 6, 312)

Left:The tattooed legs of Vaitepu, Queen of the Marquesas Islands

Evidently Stevenson intended more than just a modest travelogue and, though the planned book was never finished, his journal notes detailing meetings with chiefs, missionaries, traders, reformed cannibals and fortune-seekers later appeared as In the South Seas, published posthumously in 1896 as part of the Edinburgh Edition, and in ‘A Footnote to History:Eight years of trouble in Samoa’, London 1892.

Stevenson’s health greatly improved in the climate of the South Seas and he decided to settle in Samoa, purchasing an estate of over 300 acres, named Vailima (meaning ‘the place of five waters’). On 20 January 1890 he wrote to Lady Taylor:

here I can have some real health, I can walk, I can ride, I can stand some exposure, I am up with the sun, I have a real enjoyment of the world and of myself.

By October 1892 Stevenson found himself the owner of a large house and head of a household of five relatives and thirteen staff.

Significant items in the collection from this period include the hat, boots, riding crop and spurs worn by Stevenson in Samoa. The boots were given by Stevenson’s mother to D.W. Stevenson, the sculptor, who in turn gave them to the sculptor H.S. Gamley and by him to Lord Guthrie. The spurs, hat and riding crop were given to the collection by Stevenson’s close friend, the literary critic Sir Sydney Colvin. Perhaps most important is the tortoiseshell ring inlaid in silver with the name ‘Tusitala’ (Samoan for storyteller), which Stevenson was wearing when he died. This was given by his widow Fanny to Sir Edmund Gosse and presented to the collection by Lady Gosse.

Robert Louis Stevenson died suddenly of a brain haemorrhage on 3 December 1894 and was buried on Mount Vaea overlooking Vailima. Unfortunately, he never completed Weir of Hermiston, the book he anticipated would be his masterpiece, a view shared by many literary critics. Shocked by the suddenness of his death, many friends and acquaintances wrote their memoirs of the man, often remarking on Stevenson’s extraordinary charm. During his lifetime he achieved international celebrity, and he continues to exert an extraordinary charisma, undiluted by the passage of time.

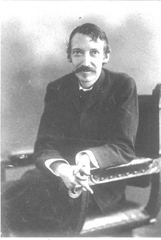

Left:Louis and Fanny onboard the Janet Nicol.

The Writers’ Museum is located in Lady Stair’s House, a seventeenth-century merchant’s house in the heart of Edinburgh’s Old Town. The building was renovated in the 1890s by the Earl of Rosebery, and given by him to the City in 1907:known as Lady Stair’s House Museum, it housed a variety of collections, but since the 1960s it has been devoted to literary collections with displays relating mainly to Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson. In 1993 the name was changed to the Writers’ Museum and five years later Makars’ Court was established outside – an ongoing project to commemorate significant Scottish writers and currently representing over twenty from the fourteenth to the twentieth-centuries. The Writers’ Museum is open Monday to Saturday, 10am to 5pm. Admission is free. All images are reproduced courtesy of the Edinburgh Writers’ Museum.

Copyright Elaine Greig 2005.

Comments