Collecting

A Shabby Habit

The secondhand book trade is a profession that for the most part has been happily loitering in cord jackets and eccentricity. Now it is faced with online competition that sells books for 10p, making £4 on postage.

The secondhand book trade is a profession that for the most part has been happily loitering in cord jackets and eccentricity. Now it is faced with online competition that sells books for 10p, making £4 on postage.

I have worked part-time in the trade for seven years. My bibiomania began in Paris, overheated in Greece and has finished with cold hands and heaters in the insalubrious West Port, in Edinburgh. This is home to five secondhand bookshops, a couple of interesting antique shops and three highly conspicuous strip joints. Arranged on three corners, the strip clubs give the area its affectionate nickname: The Pubic Triangle. It is a strange area befitting strange trades. Being in the (bookshop) business is like working in the kind of place where left socks and teaspoons might turn up. Failing that, there’s always Norman Gask’s Old Silver Spoons of England for a bit of light browsing.

I’m young enough to appreciate the huge commercial potential of the Internet but sentimental enough to like my bookshops dusty, quirky and possibly dangerous. The last quality being a fait accompli for most places these days.

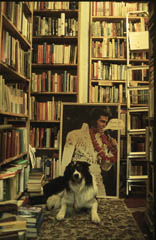

Armchair books, my place of work, has been owned for the last ten years by David Govan, although it was already a secondhand bookshop of sorts for many years before. Under his eccentric guidance it has achieved an aesthetic charm sadly incompatible with health and safety regulations. A waist-coated young official recently informed us that the innovative lighting arrangements, numerous rugs and necessary ladders were all catastrophes waiting to happen. It was a good job we hid the dog.  In any case, a sense of humour seemed to be the only recourse and we duly apologised to our customers.

In any case, a sense of humour seemed to be the only recourse and we duly apologised to our customers.

To compete with the Internet, old-fashioned booksellers, like us, must not just buy a computer, but use one effectively. We have acquired two computers, which are old and ineffective, sentient and sarcastic. Efficient productivity is as yet unknown to us. Many secondhand booksellers do not even have their books catalogued and rely on the simple expedient of knowing where a book can be found, somehow, or waving a customer in the direction of a section (not alphabetically arranged). This is an approach I have familiarised myself with over the last seven years. I’ve even perfected an accompanying facial grimace, which suggests at once yes, we might have it if you look hard enough and no, we might not, but you might find something else. I favour another gesture if someone asks for Dan Brown, but that’s quite another story.

Shop selling is a slow-paced activity, but Internet selling is like swapping the elegant prose of Jane Austen for the raunchy revelations of a blogger. It really is a case of ‘access all areas’. The only prerequisite for an amateur to become an Internet seller is a good connection and a reliable postal service. According to Abebooks.com, the world’s leading online marketplace, 13,500 booksellers worldwide list more than 80 million books on their site. No good ever comes of gentlemen amateurs buying and selling; they will either become systematic losers or acquire shabby habits, said Milton, quoted in Holbrook Jackson’s Anatomy of Bibliomania. But gentlemen are not in vogue, as they once were, and customers value choice. The Internet allows people to browse a huge selection of tomes in the comfort of their own homes. The only required mental cogitation is the translation of book descriptions into clear English.

Armchairs mysteriously acquired a slim volume about hand-to-hand combat, with (overly) detailed illustrations. Once upon a time it would have languished on a shelf, probably in hobbies, but the day after online listing it was snapped up by an enthusiast and jetted off to America. Who would have thought? is my common refrain whilst processing orders. Each order, however, is appreciated.

In the shop, quieter than it used to be, customers browse festina lente with either a belief in serendipity or a mulish determination to find that book. Outside, or up there – wherever cyber space may be – a few lines of an address are all I know about most customers. I never have to meet them, nor they me. This is not really good or bad, just different. But business, regardless of whichever dimension you trade within, is tough. The only certain thing, I hope, is that the success of any bookshop, including ours, will come down to the quality of the books.

© Hannah Adcock

This article first appeared in the The Oldie. www.theoldie.co.uk

Comments