New Voices

Alone in Alaska, haunted by Hackney or catching birds in a poultry processing plant – I often wondered what inspired authors to write their first book. At the popular Debut Authors’ Festival held at the Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh, I was quickly finding out. The festival gives audiences the chance to discover new voices at the start of their careers and also to hear writers they might otherwise overlook – perhaps because their publishers couldn’t afford a Waterstone’s plug?

Alone in Alaska, haunted by Hackney or catching birds in a poultry processing plant – I often wondered what inspired authors to write their first book. At the popular Debut Authors’ Festival held at the Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh, I was quickly finding out. The festival gives audiences the chance to discover new voices at the start of their careers and also to hear writers they might otherwise overlook – perhaps because their publishers couldn’t afford a Waterstone’s plug?

Unshackled by the cult of the individual, the festival plumps for panel discussions centred on a theme. Audiences chose events ranging from the light-hearted ‘Escaping the Day Job’, to the worryingly popular ‘Dark Imaginings of the Mind’. Authors did a short reading before discussing influences. The festival also included talks and events by various industry experts and a popular Unpublished Writers’ Jam session. It was all very energetic and intimate, with a vibrant dynamic between panel members, chairpersons and the audience. The only slight problem was one of acclimatisation as authors and audience moved from the blazingly hot Traverse Bar to the frigid environment of Traverse 2. But one must suffer for one’s art and the audience seemed keen enough. I attended four of the seven events, foregoing the intermittent sunburst outside for a different kind of illumination.

The festival kicked off with the jam session. An assortment of literary hopefuls read extracts from their unpublished work. The dominant genre chosen was the psychological thriller, which partly explains the popularity of the Dark Imaginings events. It also led to some less than enthusiastic comments by one of the judges, Literary Editor Alan Taylor, who seemed to find the genre a trifle over-worked. But the judges were affable and generally kind, sensitive to the fact that it takes immense guts to read work in progress to a host of strangers. Although they liked John Mitchell’s peculiar child-adult book, The Homemade Child, they chose Sean Manning as the winner. His comic novel, Pizza Good Times, follows his hero through the trials and tribulation of wiping tables and dressing up as some kind of pizza restaurant mascot. It was nice to see a presentable young man like Manning, (probably university educated), making the most of a Crap Job. Mark Stanton, literary agent at Jenny Brown Associates, has promised to read his manuscript.

One of last year’s participants, Rosy Barnes, managed to hook an agent after her reading. Perhaps her comic novel, Sadomasochism for Accountants will be hitting your local bookshop soon. She blogs on The Book Bar: ‘it is easy to forget that new writers also need a bit of advice and encouragement now and again. In just three days The Debut gave me the opportunity to try out my work in front of an audience, get advice from experts in the trade as well as the chance to participate in a host of stimulating events.’

The second day of the festival began with ‘Escaping the Day Job,’ a topic dear to many people’s hearts. Lois Pryce gave up a tedious job at the BBC to ride her motorcycle solo from Alaska to South America, Guy Grieves left the office behind for life in the wilds of Alaska, and Mark McNay used his experience in a chicken processing plant to write Fresh. McNay immediately gained audience sympathy because he had worked in a hideous poultry place for three months before he was sacked. His forced departure was somehow cheering – until he read an extract about messages being shoved up chickens’ bottoms. Anyway, with his shy smile and his soft assertion that he ‘always had a rebellious side,’ McNay made you want to like him. He is also a confirmed dreamer who used to ‘find offices exciting because you knew everyone’s imagination was fuelled by boredom.’ His novel’s hero, Sean O’Grady, indulges in Walter Mitty fantasies.

Pryce was initially a little harder to fathom: she had left school at sixteen, taken a succession of temporary jobs and then, in her twenties, got a job working in the BBC’s music department -but this did not turn out to be her dream job. Apparently the Beeb is a place where you work in ‘pig pens’, they use your bonus to repaint the walls beige, and the best kick you can hope for is listening to your boss complaining that his new toilet seat hasn’t arrived. After Pryce made this point I started to understand her decision to chitty-bang off into the wild blue yonder. She started out by blogging about her trip before turning it into a book, Lois on the Loose.

Grieve teased Pryce about her motorbike. He is a man very much in touch with nature, his masculine side and armchair philosophizing. His transport method of choice is a dog team. He chose to read an extract in which an old codger of a dog gets him safely home through a blizzard: if the dog had failed him, he would have died. He came close to the end many times, on one memorable occasion because he wore a kilt at an Indian festivity. Call of the Wild sounds exciting and tender, but I had a few problems with Grieve’s love of mankind: ‘I loved every job… I love people labouring or in factories,’ he enthused. The thing that tipped him over the edge and out of Britain was having to ‘submit to the will of the Lords of Suburbia’. He’d lost me a little at this point, but I think he was talking about golf.

‘Britain Today’, had a very different atmosphere. Out went the light-hearted bantering and in came social agendas and multiculturalism. Libby Brooks interviewed children from ‘all backgrounds’ for her book The Story of Childhood, Lynsey Hanley drew on her own experience of growing up on a council estate to write Estates – An Intimate History, and Sarfraz Manzoor wrote a memoir about his childhood, Greetings from Bury Park. These three shared the rhetorical polish that you might expect from journalists. Teacher Daljit Nagra, while not a professional pundit, was no less interesting. He used his experiences as a second generation Indian to compile his debut poetry collection Look We Have Come to Dover.

The discussion revolved around what it was like to be located on the fringes of society – council-housed working class, children, Muslim or Indian (first and second generation). I presume mainstream society is (or was) defined as the preserve of the white adult middle class. Hanley crackled with conviction, talking about how ‘the world seemed to stop at the edge of every estate.’ She thought the Thatcher home-owning policy initiative ‘denigrated the state of renting’ and was concerned that social mobility has been shown to be on the decline. Brooks saw childhood becoming ‘this crucible where adults can grind up their anxieties’; she recounted how the story of a poor but ‘honourable thief’, a child, made a deep impression on her. Manzoor said that he didn’t see his own life reflected back in literature – which helped prompt him to write his memoir. Dajit was rather less personal about the whole British business, maintaining, rather engagingly, that the English language ‘is the main character’ in his collection. Much of this discussion was fascinating, even if the right-on posturing could be a little tedious. Who is this ‘typical, happy, middle class child’? But Manzoor’s reading provided a counterpoint – sad and sentimental, but also very funny. He described how he had cried when he found out that he was a Muslim because he had just seen Christ crucified on TV and wanted to feel sorry for him. He also discussed his love for Bruce Springsteen’s music, which just goes to show that stereotypes are there to be exploded.

‘Love Against the Odds’ was an event that had me wriggling in my seat, slightly embarrassed. I always think books about love are best read privately, but then I’m very English. James Hopkins wrote about a love affair between a married Polish woman and an Englishman. After having lived in Poland under communism, he was well placed to describe the difficulty of living in a different culture where ‘body language becomes so important’. Hopkins’ body language said only one thing – tired. Apparently he had sleep deprivation after his hotel had turned out to be in close proximity to stag party haunts. Julian West explores obsession, ‘with a slight element of sadomasochism’ in her book Serpent in Paradise, set in conflict-torn Sri Lanka. Inspired by Joseph Conrad, she deftly uses symbolism to explore the dark hearts of characters and country. Priya Basil’s debut Ishq and Mushq is a three-generation saga, quietly funny and subtly intelligent. Her title means ‘love and smell’ in Hindi, ‘two things that you can’t hide’.  Basil said that there are lots of words in Hindi for love – to express different intensities of emotion. Her novel deals with a number of different kinds of love – and also with how love evolves. ‘To love is to suffer’ said Priya, quoting Woody Allen. With a realism not always found in the younger generation, she explored how couples are ‘ennobled by constancy’. She threw in a large element of denial to make the whole mess more interesting. Annie Freud was more erotic and blunt (a strange combination). In her collection of poems, The Best Man That Ever Was, she describes a vibrator and spanking, at least those were the two I remember. ‘Poetry comes from the floor’ said Freud, gesturing to make sure the audience were following. She then said, to general approval, that her poems were about how you could ‘really, really love someone and still hate their clothes’.

Basil said that there are lots of words in Hindi for love – to express different intensities of emotion. Her novel deals with a number of different kinds of love – and also with how love evolves. ‘To love is to suffer’ said Priya, quoting Woody Allen. With a realism not always found in the younger generation, she explored how couples are ‘ennobled by constancy’. She threw in a large element of denial to make the whole mess more interesting. Annie Freud was more erotic and blunt (a strange combination). In her collection of poems, The Best Man That Ever Was, she describes a vibrator and spanking, at least those were the two I remember. ‘Poetry comes from the floor’ said Freud, gesturing to make sure the audience were following. She then said, to general approval, that her poems were about how you could ‘really, really love someone and still hate their clothes’.

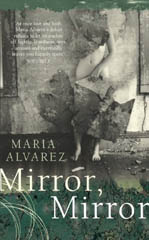

The last day of the festival began with dark imaginings of the mind, not mine, but those of four ingenious authors: Steven Hall, Jonny Glynn, Maria Alvarez and Lesley McDowell. Chairperson Catherine Lockerbie introduced the quartet, confiding ‘I’ve got a panic button under my chair.’ Steven Hall needs little introduction because his mind-eating shark is one of the weirder literary creations to be fed to the public this year. Hall seemed to be a mild mannered young man. When asked about how he felt doing nasty things to his protagonist, he replied sweetly, ‘just because they’re not real, it doesn’t mean I don’t feel bad about it.’ Glynn was inspired to create a monstrous psychopath by the brutal day-to-day events in Hackney, where he lives. The Seven Days of Peter Crumb sounded like a book I would need to read through a thick pillow and I prayed such a passionate and imaginative man would soon move to a nice, quiet suburb. ‘What does it say about me that I can imagine this?’ he asked. I hoped his question was rhetorical.

Scottish journalist, McDowell, said she was interested in ‘presence and absence

… that tension to do with lack’ and The Picnic was a kind of ‘post Freud Jane Eyre’ in which she chose very carefully what to reveal and conceal.  In Mirror, Mirror Alvarez took the tried-and-tested bored housewife and dropped her into a psychological swamp. Inspired by cult filmmaker David Lynch and poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, as well as drawing on her own training in psychoanalysis, Alvarez plays with the idea of a doppelganger, ‘that person who represents all your unconscious wishes.’ Alvarez used to ‘wake up in the middle of the night feeling very anxious’ whilst working on the novel. It seems likely that a reader will be similarly affected.

In Mirror, Mirror Alvarez took the tried-and-tested bored housewife and dropped her into a psychological swamp. Inspired by cult filmmaker David Lynch and poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, as well as drawing on her own training in psychoanalysis, Alvarez plays with the idea of a doppelganger, ‘that person who represents all your unconscious wishes.’ Alvarez used to ‘wake up in the middle of the night feeling very anxious’ whilst working on the novel. It seems likely that a reader will be similarly affected.

Emerging blinking into the Traverse Bar, crowded with people who had not started the day with man-eaters, psychopaths or the unconscious longings of desperate housewives, I decided to gets some fresh air. The intimacy of the event had captivated my imagination and I needed time to disconnect. What could be negatives – the size of the festival, its relative lack of publicity – turned out to be assets, the very things that make it successful. What is it they say about good things and small packages?

© Hannah Adcock

Comments