May Revels and Roslin

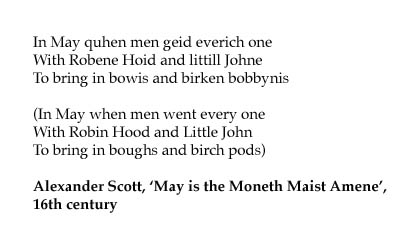

Conjuring bucolic scenes of thatched cottages and village greens, haywains and cloudy cider, Robin Hood and his reprobate band are associated with medieval England rather than with Scotland. But they were central figures in Scotland’s traditional ‘May plays’ – bawdy, boisterous affairs celebrating fertility and rebirth. Gypsies who visited Roslin in the spring and summer performed them for their patrons, the St Clair family, and for local villagers. May was a season of revelry and mischief when normal strictures were relaxed. On the last night of April, young men and women would pair off in ‘greenwood marriages’, and early on May Day morning they would dance around the May poles. The lewd antics and knockabout humour of the Robin Hood plays was an important part of these festivities and fertility rituals.

Conjuring bucolic scenes of thatched cottages and village greens, haywains and cloudy cider, Robin Hood and his reprobate band are associated with medieval England rather than with Scotland. But they were central figures in Scotland’s traditional ‘May plays’ – bawdy, boisterous affairs celebrating fertility and rebirth. Gypsies who visited Roslin in the spring and summer performed them for their patrons, the St Clair family, and for local villagers. May was a season of revelry and mischief when normal strictures were relaxed. On the last night of April, young men and women would pair off in ‘greenwood marriages’, and early on May Day morning they would dance around the May poles. The lewd antics and knockabout humour of the Robin Hood plays was an important part of these festivities and fertility rituals.

No one knows when the gypsies first came to Roslin, although Father Richard Augustine Hay, author of Genealogie of the Sainteclaires of Roslin (1700), tells us that it was in the time of ‘Sir William Sinclair of Roslin, knight’, who became Lord Justice-General in 1559:

he delivered once ane Egyptian from the gibbet in the Burrow Moore [Boroughmuir], ready to be strangled, returning from Edinburgh to Roslin, upon which accoumpt the whole body of gypsies were, of old, accustomed to gather in the stanks of Roslin every year, where they acted severall plays, dureing the moneth of May and June. There are two towers, which were allowed them for their residence, the one called Robin Hood, the other Little John.

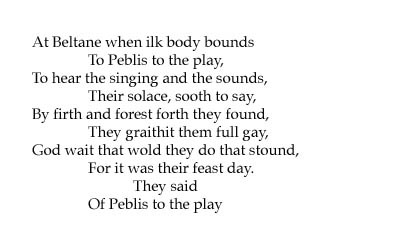

The first record of gypsies in Scotland was in the early 1500s. On 22 April 1505, the Lord High Treasurer entered into his accounts, ‘Item to the Egyptianis be the Kingis command, vij lib.’ On 3 July 1505 James IV gave ‘Anthonius Gagino, Earl of Little Egypt’ a letter of commendation to the King of Denmark and in 1530 gypsies danced before King James V: ‘Egyptianis that dansit before the king in Halyrudhous [Holyroodhouse]‘ received forty shillings. It has been argued that either King James V or King James VI was the author of ‘Peblis to the Play’, an anonymous poem about the May festivals in Peebles.

People of all social classes saw the month of May as an excuse for drinking, dancing and illicit unions. For a time, the clergy tolerated these antics, but by the mid-sixteenth century they were denouncing them from their pulpits. It is ironic that we are largely reliant on records compiled by outraged priests and magistrates to discover what the May celebrants were actually doing.

The English Puritan pamphleteer Philip Stubbes rants in his The Anatomie of Abuses (1583), ‘of fortie, threescore, or a hundred maides going to the wood over night, there have scarecely the thirde parte of them returned home againe undefiled.’ At dawn the Maypole would be raised: a huge tree trunk, painted brightly and decorated with ribbons, flowers, herbs and budding foliage, which Stubbes denounced as ‘a stinking idol’, warning that the ‘prince of Hell’ reigned over these ‘heathen’ proceedings. But less sinister characters presided over the revels – the Lords of Misrule. These Kings of the May, Abbots of Unreason, Abbots of Narent, Lords of Inobedience, Priors of Bon Accord and Abbots of Unrest acted as ceremonial leaders of the festivities. At the beginning of the sixteenth century the May Kings, Lords and Abbots and their attendants were gradually superseded by Robin Hoods, Friar Tucks and Little Johns.

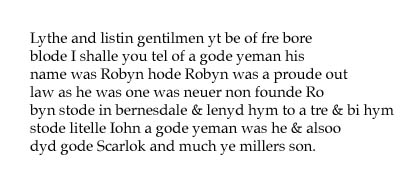

Robin Hood ballads were as popular in the taverns and fields as the romances of King Arthur were in grand halls and courts. Scots chronicler Walter Bower wrote in the 1440s, ‘Then arose the most famous murderer Robert Hood, as well as Little John together with their accomplices, from among the dispossessed and the banished whom the foolish people are so inordinately fond of celebrating in tragedy and comedy.’ One of the most precious items held by the National Library of Scotland is a single volume comprising the Chepman and Myllar prints, bound in with A Gest of Robyn Hode, printed in Antwerp around 1510.

The attitude of the authorities towards Robin Hood and May Day revelry underwent a radical transformation within less than fifty years. In 1508 in the burgh of Aberdeen it was ordained that ‘all persons who were able’ should be ready with their ‘arrayment’ made in green and yellow, ‘bowis, arrowis, and all other convenient things’ to join a procession with ‘Robin Huyd and Litile Jonne’. In 1555 the May games were abolished by an Act of Parliament stating: ‘in all times cumming na maner of persoun be chosen Robert Hude nor Lytill Johne, Abbot Unreason, Queen of Maij nor utherwyse, nouther in Burgh nor to landwart in ony tyme to cum’. Women and ‘uthers’ who were caught singing summer songs faced ‘the cuckstulis’, the ducking stool, with imprisonment or exile the punishments for playing the characters. Even in the face of such draconian punishments, the traditions persisted. In 1561, John Knox noted ‘the rascal Multitude’ gathering in Edinburgh ‘efter the auld wikket manner of Robyn Hoode… which enormity was of many years left off and condemned by Statute and Act of Parliament; yet would they not be forbidden, but would disobey and trouble the Town’.

The year before, the printer William Copland had entered a Robin Hood play in the Stationers’ Register. He included two May plays – ‘Robin Hood and the Friar’ and ‘Robin Hood and the Potter’ – in his A Mery Geste of Robyn Hoode and of Hys Lyfe. The first text recounts the famous meeting of Robin Hood and Friar Tuck.

Twenty years later, the people of Scotland were still refusing to give up their May games. On 2 May 1580 the Kirk Session in Perth condemned men and women who had processed through the town piping and striking drums as they made their way to ‘the dragon holl’- the dragon hill. The Kirk’s threat of a twenty shilling fine was not sufficient disincentive, for in 1591 the Perth Kirk Session was still denouncing the ‘filthy and ungodly singing about the Mayis’.

A sanitised version of the May festivities was superimposed on the tradition in Victorian times, with a wholesome Merrie May Day that celebrated the innocence of childhood rather than potency and fecundity. The May Queen was no longer a wanton, wild Maid Marian; she was simply a village schoolgirl with blossoms in her hair. One example of this twee version of the ancient rituals was the 1902 Roslin Gala Day, which featured a ‘Peace’ parade of children, marking both the end of the Boer War and the coronation of King Edward VII. The procession wound through the village following two pipers, its centrepiece a brightly decorated cart on which sat two boys and two girls. When they reached the park, the village girls danced around a Maypole while the boys performed military gun drill and bayonet exercises. The Green Men of Roslin Glen were nowhere to be seen.

A sanitised version of the May festivities was superimposed on the tradition in Victorian times, with a wholesome Merrie May Day that celebrated the innocence of childhood rather than potency and fecundity. The May Queen was no longer a wanton, wild Maid Marian; she was simply a village schoolgirl with blossoms in her hair. One example of this twee version of the ancient rituals was the 1902 Roslin Gala Day, which featured a ‘Peace’ parade of children, marking both the end of the Boer War and the coronation of King Edward VII. The procession wound through the village following two pipers, its centrepiece a brightly decorated cart on which sat two boys and two girls. When they reached the park, the village girls danced around a Maypole while the boys performed military gun drill and bayonet exercises. The Green Men of Roslin Glen were nowhere to be seen.

Mark Oxbrow is co-author of Rosslyn and the Grail, with Ian Robertson. It is published by Mainstream Publishing, ISBN 1845960769 HBK £15.99.

© Mark Oxbrow 2006

Comments